Social care commentary: multi-agency safeguarding arrangements

Ofsted’s National Director of Social Care,Yvette Stanley, discusses the important ingredients for multi-agency safeguarding arrangements to improve the response to children in need of help and protection:

Safeguarding children requires a multi-agency response. It cannot be done by local authorities alone. This is true across all aspects of safeguarding arrangements: from the frontline practitioner identifying a child at risk and making a referral to the local authority, through to leaders determining local strategic and operational responses to child protection issues. We must get this right for all children who experience abuse or neglect.

With the publication of the new ‘Working together to safeguard children’ and local areas moving to new multi-agency safeguarding arrangements for children, this seems an opportune moment to talk about the important factors that we see enabling effective local multi-agency arrangements for safeguarding. What happens at a strategic level matters. It can lead to improvements in the support, protection and care that vulnerable children receive. It can also lead to the opposite if arrangements are not working.

I want to talk about our findings in our Local Safeguarding Children Board (LSCB) reviews and our joint targeted area inspections (JTAIs).

When talking about multi-agency safeguarding, we always need to ask the question, ‘What does this mean for children?’

We do not think it is appropriate to prescribe any 1 model of working. What we would like to see is that as agencies set up their new arrangements, they remember the ingredients that worked in their previous ones while challenging themselves to innovate and learn from the experience of others.

What we have found and what we would like to see

The best local safeguarding arrangements are developed from a shared vision and shared values. It is about all agencies involved being ambitious to secure the very best responses to children at risk of harm in their community. Local safeguarding arrangements work well when there is a clear line of sight on both the operational and the strategic response locally. Agencies need to know the quality of their frontline practice. They must understand the direct experiences of children and their families in their local area.

Without good leadership, safeguarding arrangements will fail. This means that each of the 3 lead safeguarding partners must step up to the task in hand: the police, health and the local authority. It means working together to ensure a joined-up local response to reduce the risk of harm to children. This is about leaders who understand their local context. Children and their families do not live in silos, so it is critical that leaders create an environment in which multi-agency working can flourish.

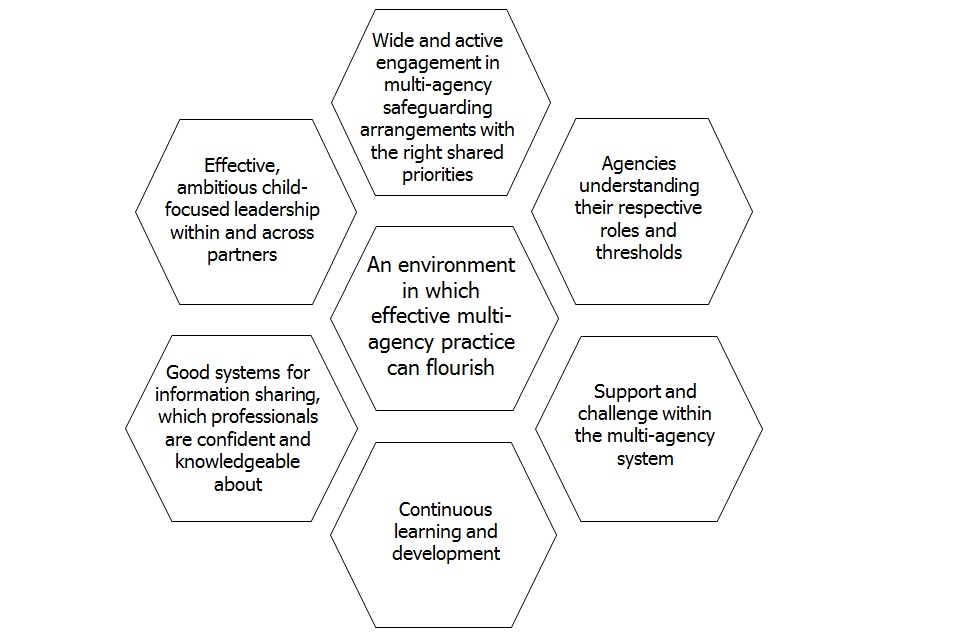

Components of successful partnerships

The JTAIs have helped identify what the components are for good multi-agency working. I will go into each of these in more detail throughout this commentary.

Effective, ambitious child-focused leadership within and across partners

It is important that the lead safeguarding partners articulate and communicate a clear vision across the local partnership. This should include the message that child protection is everybody’s responsibility. They need everyone involved to commit to a joined-up approach to improving the response to vulnerable children. All partners need to have a clear vision for multi-agency practice, which is shared with all staff.

Understanding local need and using information to protect children

We have found that the LSCBs that influenced practice most effectively receive the right information from across different agencies, including from multi-agency audits. They then analysed this information to:

- understand local need

- get an understanding of frontline practice

- develop well-informed priorities

- decide what action to take to improve frontline services

Some areas have used performance data, qualitative information and their local strategic needs analysis exceptionally well to identify their priorities and take action to protect children. It is important that lead safeguarding partners ensure that they have access to the right information to enable them to take effective action.

For example, in Camden the board noticed a clear correlation between children who self-harm and parents who have mental health problems. This led to a multi-agency audit on parental mental illness. As a result, it became a priority work area for the board.

It is not just about knowing what is happening on the frontline but responding to it effectively. There are 2 other good examples from Camden to illustrate this:

- When there was a high incidence of hate crime near a particular school, information was quickly shared with the LSCB. It was seen as a multi-agency responsibility. This good network and strong communication enabled swift and clear messages to be given to parents, along with advice on how to access support.

- When it became evident from a high number of referrals from a specific school that child sexual exploitation was a particularly prominent issue, Camden promptly used its resources to organise additional training and support for school staff.

We also found some excellent examples from other areas.

In Cheshire West and Chester, the LSCB and the local authority have worked collaboratively to develop a set of ‘neglect indicators’. This has enabled them to map early help and children’s social care activity about neglect and to assess demand and need across the area.

In Lincolnshire, strategic arrangements for managing and overseeing work to combat domestic abuse are well developed. They are based on a strong understanding of the extent and nature of domestic abuse and are having a good impact across services. Our report said:

There is good awareness and ownership of the domestic abuse joint protocol by frontline staff across agencies. There has also been a strong focus on equipping frontline staff.

Strategic action plans are well considered and comprehensive, and are underpinned by a strong shared vision and ambition to reduce incidents of domestic abuse and prevent their re-occurrence. Senior leaders across the range of Adult and Children’s Safeguarding Boards, the Public Protection Board and the Community Safety Partnership have a detailed understanding of the prevalence of domestic abuse and the impact on children in their area.

The partnership in Lincolnshire has an effective domestic abuse strategy and a comprehensive joint protocol to guide all professionals working with those affected by domestic abuse. The Adults’ and Children’s Safeguarding Boards and the Domestic Abuse Strategic Management Board developed this protocol. Hundreds of frontline professionals attended its launch at a learning event. This, together with a wide range of training, means that many staff across agencies now have the knowledge and assessment tools required to better understand and manage risks related to domestic abuse. We found that practitioners across the partnership were aware of the protocol and that many were using the resources to good effect. For example, routine enquiries about ‘domestic abuse, stalking and honour-based violence assessments’ are now well embedded in frontline staff’s practice across all three NHS trusts. Multi-agency risk assessment conferences help to maintain a vigilant approach to managing high risks.

Wide and active engagement in multi-agency safeguarding arrangements

It is essential that the lead agencies ensure that there is wide and active engagement in multi-agency safeguarding arrangements by other partner agencies, including in the voluntary sector, education and adult services. Otherwise, partners across other agencies do not own, understand or implement multi-agency strategies and the strategies will not have the required impact for children.

For example, at a strategic level there may be lots of work to develop neglect strategies and tools. But if frontline staff across all agencies, including adult services, do not understand or use the tools the strategy will be ineffective. In Cheshire West and Chester, we saw a wide range of agencies including youth offending services involved in developing a neglect strategy and in providing the training. The impact was that their staff owned and used the tools to good effect, increasing recognition of children living with neglect.

Getting the priorities right.

Challenges will be different in each local area.

The best LSCBs have not been over-reliant on the local authority’s information, but use information from across the partnership. The information enables them to:

- ask the right questions

- identify the right priorities

- take the right actions

For example, in Camden the board’s priorities are clear. They are based on a thorough analysis of local needs and reflect learning from serious case reviews, both locally and nationally. All board partners are able to explain the board’s priorities and give examples of how they work collaboratively to deliver them.

Not being clear about the priorities can lead to poor practice. When LSCBs are judged to be inadequate, they have often not prioritised child protection sufficiently or do not understand important aspects of it well enough. It is important that the partners maintain a very clear focus on the protection of children, including early help and protecting those who are looked after or care leavers.

Ensuring a joined-up approach

Local safeguarding arrangements need to be closely aligned with the priorities of other strategic bodies, such as the adult safeguarding board (ASB), health and well-being board and the community safety partnership. ‘Working together’ makes it clear that in the new arrangements the leaders must make and maintain these links.

Good strategic links between partners’ objectives and priorities and those of other decision-making bodies are essential. You need the right connections to deliver effective multi-agency working.

In our JTAI about children living with domestic abuse, this was very apparent. We found that it was vital to have clarity of roles and to share information between the community safety partnership, LSCB, ASB, and health and well-being board. This should lead to shared priorities, a shared ownership of work and a joined-up approach to commissioning services.

We saw this working well in Islington, where the LSCB has worked with the Youth Justice Management Board to revolutionise the local response to gangs and youth violence.

Agencies understanding their respective roles and thresholds

Involving all partner agencies

While the new safeguarding arrangements focus on the local authority, the police and health, it is essential that other safeguarding partners such as the voluntary sector, education and adult services are involved and have ownership of multi-agency working to protect children.

For example, the importance of schools and early years settings is explicitly referenced in ‘Working together’.

Their role in identifying and supporting vulnerable older children is significant. We found some very positive examples of schools supporting children experiencing multiple forms of abuse in the JTAI about children living with neglect.

In Bristol, we found that the partnership prioritises and supports schools’ role in safeguarding children. There is very good engagement with and support for schools through the safeguarding in schools team. Early help managers have helped schools to identify and respond to neglect effectively.

Bristol’s strong work in schools to support children who are identified as suffering from neglect means that concerns about individual children and families are identified at an early stage. The report noted:

… work of the learning mentors, family support workers or home-school workers is, in many cases, highly effective in identifying and monitoring older children who suffer from neglect. School budgets also fund therapies such as art and play, which can help to meet the needs of children and so prevent the need for a referral to children’s social care. The good relationships between school staff and children’s social care staff mean that support and guidance is available to support the referral process. School staff’s knowledge of children and their families in their community is a great strength in enabling support for older children experiencing neglect.

Understanding professional practice and valuing professional disciplines and expertise

In partnerships that have a strong grounding in professional practice and a shared commitment to protecting children, it is likely to be more straightforward to agree priorities and work together.

In my view, there needs to be a good understanding of professional practice to enable good quality decision-making at a strategic level. The challenge is how this is achieved while making sure that the arrangements allow timely decision-making. We have seen a number of ways that LSCBs have achieved this. But the important message is that the best multi-agency strategic arrangements are based on a very good knowledge of professional practice.

An example of this issue is in the multi-agency front door (the initial point of contact when someone has concerns about a child). Here, multi-agency decision-making can happen virtually or through co-location. Different agencies and professionals always have a variety of expertise. Valuing that range of expertise and difference in perspective and focus is critical. Bringing it all together leads to better decision-making.

However, simply sitting in the same room as one another is not enough. Inspectors have found instances of agencies located together but still missing opportunities to share information and make joint decisions. All agencies must understand their own and each other’s roles, no matter where they are located.

Understanding of thresholds and different roles and responsibilities across agencies remains a significant challenge across all aspects of children in need and child protection. For example, in the recent neglect JTAI some professionals were not aware of the role of community rehabilitation companies (CRC) and the national probation services (NPS). Therefore, they did not always share appropriate information or seek information about children linked to adults involved with these services. We are finding this lack of understanding of thresholds in emerging areas of concern such as ‘county lines’ and criminal exploitation.

Good systems for information sharing which professionals are confident and knowledgeable about

We are still finding examples of confusion and poor practice when it comes to information sharing. This is directly impacting on children.

Examples include:

- a school that reported to an inspector that they could not share information about domestic abuse unless they had the parents’ permission

- different health professionals working with older neglected children not sharing information about the same child so that each one does not have the most up-to-date information about all aspects of a child’s well-being, health and sexual health

- nurses not always sharing relevant information when there are indicators of child sexual abuse

- information not always being shared with CRC and NPS, and information about children linked to adults involved with these services not being requested

Better examples of information are also evident. In Hampshire, ‘IT systems ensure that agencies can access and share information. For example, multi-agency safeguarding hub (MASH) health practitioners have access to the children’s social care records. The recent facility for health services to have access to a number of GP summary care records for adults and children has been helpful, both in enhancing initial information gathering and the quality of risk assessment within the MASH.’

In Wiltshire, MASH practitioners hold a daily domestic abuse conference call to discuss domestic abuse cases and share information in a timely manner across multiple agencies.

Strong support and challenge within the multi-agency system

We know that high support and high challenge can create an environment in which practice can flourish. This includes good quality training and supervision and needs to be in place for the whole multi-agency partnership.

Building trust and confidence between partners is complex. But we have seen agencies that are able to challenge each other and professionals who understand the processes for escalating concerns about children or for challenging decisions about children. In many of these cases, we have seen better outcomes for children. This is often an indicator of a healthy partnership. In a recent JTAI, some schools told us that because they knew they understood the escalation process and knew they would be taken seriously they felt confident in challenging decisions. We saw that this made a difference for children. The three lead partners will need to think carefully about how they build that culture of healthy challenge.

The importance of independent scrutiny is summed up well in the Stockton-On-Tees JTAI report:

The LSCB has a strong and independent identity. This means that challenges to agencies that arise from the board’s monitoring and scrutiny role carry a sufficient degree of authority to ensure that the agencies respond positively and work to address areas of weaker practice.

Section 11 audits have really made a difference in terms of scrutiny and challenge when they are carried out well. They can provide good evidence about work at both strategic and practice levels and can enable agencies to be held to account. Inspectors have seen that ‘challenge days’ can make a positive difference. This is when agencies come together to discuss the findings from Section 11 audits and to be held account for taking timely and appropriate action to address any gaps in their safeguarding response.

An environment in which multi-agency practice can flourish

All the components described in this commentary lead to an environment where multi-agency practice can flourish. Building this sort of environment should be at the heart of any new arrangements.

I have already mentioned the importance of a common purpose and understanding across partner agencies. Other important ingredients for this environment are:

- training and learning being multi-agency, where appropriate

- multi-agency auditing and subsequent ownership and action planning

- developing multi-agency tools to enable a common approach to and understanding of child protection

Cheshire West and Chester is a good example of having the right environment for multi-agency work to thrive. Its inspection report stated:

The Cheshire West Local Safeguarding Children Board (LSCB) has taken the lead in developing and promoting the use of evidence-based tools to support practice, and there is a cycle of continual review and sharpening of responses to tackle neglect. For example, learning from audit is leading to a further refinement of these tools, including the development of an assessment tool for older children. A wide range of agencies are involved in LSCB audits and the findings are widely disseminated across partner agencies, leading to improvements in practice.

Practitioners across all health services use a range of risk assessment tools provided by the LSCB, alongside specific health assessment tools, to support them in assessing the risk of neglect and to inform decisions to refer on. This was seen, in cases, to help practitioners understand the specific needs of children and the impact of neglect on children across age ranges.

Having a line of sight to practice

Multi-agency partnerships need an effective system to monitor and evaluate the impact of their work on the progress and experiences of children in their local area. They also need to act on any areas of practice that need improvement and monitor what happens next.

There needs to be a clear understanding of what is happening in frontline practice. Only then can you improve the quality of services and appropriately influence the planning and commissioning of services to help and protect children. Having a culture of scrutiny and challenge that leads to improvements in safeguarding will maintain a focus on the right issues. In our view, multi-agency audits can be a real driver of getting it right.

We know that there are points in the system where to take your eye off the ball is more risky. For example, leaders should never lose sight of the quality of referrals and decision-making at the front door. Keeping a grip on the quality of practice here is key to getting it right for children. Robust auditing activity gives senior leaders the insight that they need.

The importance of multi-agency auditing

While most areas have multi-agency audits in place, the quality is highly variable and evidence of impact as a result if not always clear. Not all partnerships are involving service user feedback in audits and not all feed back directly to staff. Therefore, learning is limited.

When multi-agency audits are done well, they enable significant insight into both individual agency practice, multi-agency practice and the impact on the lives of children and families. They act as a driver for improvement. During the JTAIs, we have found that agencies can learn as much from good practice examples as they can from identifying lessons learned from deficits in practice. Engaging staff in audits is more effective in improving practice, as is ensuring wide dissemination of the learning.

Derby uses auditing effectively to make a difference to the lives of children. When it carries out an audit and completes a review of progress, staff plan a further audit to make sure that the desired improvements happen. Derby has used this approach well when tackling the issue of neglect. When the board members recognised that improvement was happening too slowly, they acted swiftly. They more than doubled the number of training courses on neglect available and introduced a specific neglect element in mandatory multi-agency safeguarding courses. Derby then planned a further audit to assess the impact of this additional training on improving practice.

Creating a culture of continuous improvement and learning

Part of creating the right environment for multi-agency working to flourish is to create a learning culture.

A good example of this is one I am very familiar with, in Merton:

The board promotes a culture of continuous development. Learning from SCRs and learning improvement reviews is used to improve safeguarding practice and in the development of multi-agency policies. The routine and innovative use of single- and multi-agency case file audit means that the board can assure itself of the quality and impact of frontline social work practice and take decisive action to drive improvement. The collaboration of partners at both strategic and operational level allows for alerts and trends to be identified and acted on swiftly.

Multi-agency training that makes a positive difference to practice

Training helps. We think multi-agency training is even more important. Helping practitioners to have a shared understanding and be better sighted in each other’s roles can make a positive difference to frontline practice.

For example, in Wokingham we saw direct examples of multi-agency training on neglect leading to improving practice in casework with children living with neglect.

South Tyneside also has a comprehensive training offer, which the board develops through consultation and analysis. Training is evaluated to ensure that it is raising awareness and improving practice. Our report said:

The training offer is well aligned to the strategic priorities of partnerships to improve working practice in safeguarding children and improving outcomes. A strength of the workforce development group has been its merger with the training group from the Safeguarding Adults Board. This supports coordinated working on the ‘think family’ approach, especially in response to children in families in which alcohol, substance misuse, domestic abuse and mental ill health are prevalent.

In Stockton-On-Tees, we found more good learning opportunities:

[With] the LSCB conference, statement of intent, neglect training and roll-out of the evidence-based tool for identifying neglect, individual agencies are focused on enhancing the knowledge and skills of frontline staff to tackle neglect.

Recent initiatives include the local authority’s ‘topic of the month’ focus on adolescent neglect in August and September, neglect training delivered in termly forum meetings with school-designated safeguarding leads and quick awareness-raising measures, such as Cleveland police’s child neglect screensaver. Alongside the roll-out of the neglect assessment tool, the ongoing adoption of the family work model across agencies is beginning to support a sharper focus on both neglect and the lived experiences of children.

Engaging children in strategic developments.

The views and engagement of children should play a pivotal role in the work of the partnership. They should influence service developments. I would ask that as you think through how you are going to work together, you think about how the views of stakeholders can influence what you do and how you do it.

In Derby, staff have engaged children well in the process of creating and disseminating learning materials that have directly led to greater awareness and the prevention of harm, such as the short film ‘Alright Charlie’. A group of Year 6 girls used their learning from watching this film to protect themselves from harm and to provide evidence to the police that supported the successful prosecution of a perpetrator.

North Lincolnshire involves children in all areas of the board’s work, such as learning from serious case reviews. A group of children, dedicated to promoting positive emotional well-being and mental health, produced a ‘positive steps’ leaflet. They organised a conference to raise awareness of children and professionals. Children have also been at the forefront of developing the North Lincolnshire Children and Young People’s Emotional Health and Well-being Transformation Plan.

Summary

I want us to continue to debate how strategic arrangements for safeguarding children can improve multi-agency working so that children in need and their families get a joined-up, effective and proportionate response at the frontline.

As I have said before, no one agency can create an effective child protection system by itself. Only a joined-up approach at a strategic level will mean that vulnerable children receive a better response.

To test the effectiveness of strategic arrangements, we must always ask: ‘How is joint working making a positive difference to the lives and experiences of individual children and their families?’ At their very best, local arrangements show that ambitious, joined-up strategic partnership while also having a clear line of sight on practice, on the experiences of children and on the impact of that direct work.

My experience has highlighted the importance of scrutiny and challenge in partnership arrangements, for which there needs to be an independent element. I want to continue to ask the question about how independent scrutiny works best in improving multi-agency working combined with local mutual scrutiny and challenge.

We all have a responsibility to maintain a relentless focus on improving the multi-agency response to children in need of help and protection and their families. We will continue to share examples of where this has been done well, and collaborate closely with our colleagues in HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services, the Care Quality Commission and HMI Probation to monitor and raise any areas of concern. We will continue publishing our JTAI reports, which will continue to focus on multi-agency arrangements through specific themes.

‘Inspecting multi-agency safeguarding arrangements’ provides guidance on how Ofsted, the Care Quality Commission and Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, Fire and Rescue Services inspect safeguarding arrangements.

Responses