Learning From England’s Apprenticeship Expansion

President, Transatlantic Apprenticeship Exchange Forum (TAEF), Tom Bewick’s presentation to the 3rd Annual Transatlantic Apprenticeship Exchange Forum 14th November 2017, Urban Institute, Washington D.C.

It is a real pleasure to be here during National Apprenticeship Week. I would like to thank Dr. Robert Lerman and the Urban Institute for hosting my organization here once again.

The Transatlantic Apprenticeship Exchange Forum is now in its third year. We’re past our formative stage. From this year, I’m delighted that we have attracted world-class support in the form of Britain’s iconic institution, The Open University (OU) – a leading provider of degree level apprenticeships and distance learning, both in the UK and overseas. In particular, I’d like to thank David Willett of the OU and his team for their ongoing support.

As an international skills consultant, I’ve dedicated all of my professional career to the campaign to grow more high-quality apprenticeships. It’s a great pleasure once again to lead a trade mission of UK apprenticeship training organisations; nearly 20 people and organisations have made the journey across the pond.

Each of them have something of real value to offer your system since they have all played a major part in England’s apprenticeship story. Today, I want to tell you about this story; and what kicked off two decades of apprenticeship expansion.

In 1997, apprenticeships had all but died out. A youthful Tony Blair was swept into Number 10 Downing Street. Cool Britannia was all the rage; that year the UK even managed to win the Eurovision Song Contest!

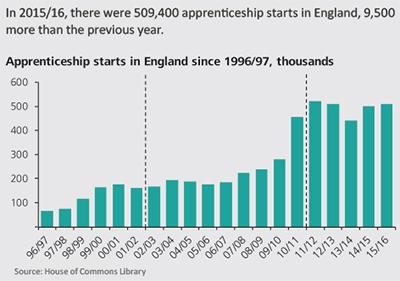

The new government, of which I was a part, committed itself to a ‘skills revolution’. The plan included the revitalization of an old idea – Apprenticeships. I want to tell you about the story of England’s expansion effort in 3 charts. In five years from 1997, the number of apprentice starts per annum had more than doubled… by 2016, the number of annual starts had increased four-fold again; with over half-a-million individual apprentices commencing on program in the last year alone. That compares with just 75,000 in 1997.

England’s expansion story

England’s latest apprenticeship ‘starts’ is a similar number of US registered apprentices; except of course, in relative terms, this has to be measured

against a British workforce of less than a quarter of the size of the US.

So, what were the main factors that drove England’s expansion success?

I would point to four key things:

- The importance of a national conversation on apprenticeship, e.g. business leadership, bi-partisan commitment and exhortation,

- The case for public investment in the off-the-job-training element of apprenticeship was made to the Treasury and won;

- Employers were placed in the driving seat of developing the content of apprenticeship programs;

- Government’s role has focused on being the guarantor of quality (which it has not always got right); as well as acting initially as the main funder of the off-job-training element of apprenticeship.

The commitment to publicly invest in the off-job training element was the gamechanger in expanding apprenticeship. Back in the 1990s, community colleges were the main players. By 2017, they account for just 25 per cent of the apprenticeship market share; even if many colleges still play a significant role in their local communities.

Over the past decade, a lot of innovation has occurred. It has seen the creation of nearly 1000 workforce intermediary training providers. Software and technology companies, like OneFile, have helped reduce the perceived bureaucracy for firms; not least by providing employers and apprentices with smart e-portfolios.

In the UK, we’ve seen the growth of credentialing and assessment organizations that help to underpin a more portable and higher quality system of apprenticeship. As a result, completion rates are as high as 90 per cent in some sectors, compared to an average completion rate of 46 per cent in

US Registered Apprenticeship.

The English model is driven by competency based standards and what Americans might call “stackable credentials”. These are transferable skills and qualifications the industry itself recognises as the requirements the apprentice needs to fulfil to effectively carry out their role.

I’m not saying that everything the English apprenticeship model has achieved has been perfect. As with any ‘dash for growth’, there will always be a temptation for some players in the market to cut corners.

For a few years, both the quality and integrity of the growing English apprenticeship system suffered. But crucially, government and industry got a grip of the problem. Since 2012, legislators have passed laws to protect the brand of apprenticeship. It is illegal for UK firms or indeed anyone to pass off a program as an “apprenticeship” unless it is part of the formally approved system. A six-month internship program, for example, cannot be badged as apprenticeship.

Since April 2017, the custodianship of England’s apprenticeship system – in terms of quality assurance – has passed to a new Institute for Apprenticeship. The Institute’s role is to ensure that programs stay relevant and deliver world-class skills to British industry. It has the power to close down schemes that are not considered highquality enough.

Today, England is spending nearly USD$5 billion per annum on the training component of apprenticeship; two-thirds of that sum is now raised directly from employers via a 0.5% payroll tax or Levy that firms can only get back if they take on apprentices.

Only 3 per cent of firms pay the Apprenticeship Levy, although 60 per cent of British employees work for Levy paying firms. The UK government is leading by example with the roll-out of new civil service apprenticeships; including a legally enforceable commitment to ensure the public sector hires at least 2.3 apprentices for every 100 workers.

Shifting perceptions

As a result of the investment and growth in apprenticeship perceptions have shifted about who the scheme is for. Two-thirds of current English apprentices are aged over 25. More than half are women.

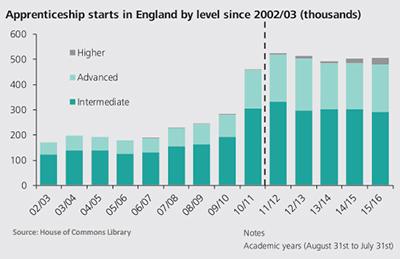

The skills profile is changing too. In the past apprentices were learning at the level of a high school diploma student. Now it is possible to do the equivalent of associate and degree level apprenticeships. Many of the big banks; IT companies and law firms are providing young adults with a completely debt-free way of earning and learning for a degree.

Did you know there are more applicants each year to the Rolls Royce engineering apprenticeship program than apply to Oxford and Cambridge Universities?

Workforce intermediaries like the Open University are leading the charge, with degree-level apprenticeships that can be delivered in the workplace and online.

As the chart shows, the number of advanced and higher-level apprenticeships has been growing in recent years. This of course is a welcome development, particularly if our societies are to challenge some of the negative and frankly outdated views about who apprenticeship is for.

Growth in non-traditional areas

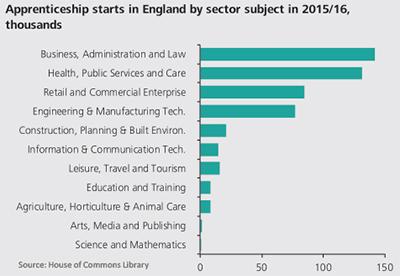

We still need to train more plumbers, electricians and construction workers. But perhaps what makes England’s evolving apprenticeship system the most expansive in the world, is the extent to which it is active in so called ‘nontraditional’ industries.

For example, there are apprenticeships in:

- Golf Course Manager

- Pest Control technician

- HR advisor

- Teaching assistant

- Geospatial survey technician

- Cyber intrusion analyst

Apprenticeships in these roles, from entry level positions right up to management and leadership roles, is helping to challenge wider cultural perceptions that somehow apprentices are relatively low-skilled, or available only in the manual trades.

Matching England’s performance

American has embarked on another epic journey. According to Marc Benioff, CEO of Salesforce, your nation should set a moon-shot goal of 5 million apprenticeships over the next 5 years. Your President and his adviser, Ivanka Trump, appear to agree with the need to massively scale-up.

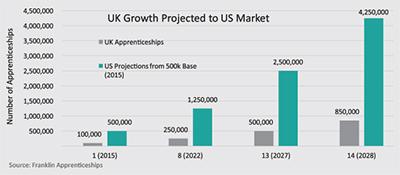

The chart above shows the scale of growth required over the next 10 years if the U.S. were to match England’s growth performance – equivalent to about 4 million apprentice starts every single year from 2028.

Taking the benchmark figure of the current 500,000 registered apprenticeships, it would require that by 2022, American apprenticeships would have to more than double to 1.2 million starts per annum; and by 2028 perhaps more than treble.

It is possible, provided:

- You learn from England’s mistakes – the ‘dash for growth’ is a road paved with unintended consequences;

- Focus rigorously on quality, as well as quantity (protect the brand and set up an independent challenge function, like an Institute for Apprenticeship);

- If you do regulate, try and regulate the intermediaries and the ecosystem, not the employers;

- Redirect and rebalance traditional post-secondary education spending towards employer incentives to take on and train more apprentices;

- Remember that government and the public sector have a key role to play to lead by example.

I will close my remarks by revisiting something a famous Anglo-American once said:

“You can always count on Americans to do the right thing – after they’ve tried everything else.” – Winston Churchill

Given the fact students face $1.3 trillion of debt; the skills gap is widening and four-year college is no longer the passport to prosperity it once was;

clearly now is the time to expand American Apprenticeships.

Responses