A proven model for a new vocational system and pedagogy

In my last piece ‘How must FE change to be a successful tool to solve the Skills Gap Problem in the UK?’ I mentioned that there was a model already in existence which shows us the way forward for new vocational training systems.

It is called Leerpark and I was able to work with its founder Max Hoefeijzers to understand what it is and why it has succeeded.

Two recent reports by McKinsey and The Centre for Economic Inclusion 2015 UK starkly highlighted two associated problems, which are a blight on our society and economy, a large number of unemployed young people and a shortage of people qualified for jobs which employers have.

In their report of 2012 ‘Education to Employment: Designing a System that Works‘, (reissued in 2017)

McKinsey conducted research worldwide studying a sample of;

‘more than 100 approaches in 25 countries. As a result, we have developed a truly global perspective on what characterizes successful skills-training systems. To build a strong empirical base, we also surveyed more than 8,000 young people, employers, and education providers in the nine countries that are the focus of this research.’

Their conclusions were;

‘high levels of youth unemployment and a shortage of people with critical job skills. Leaders everywhere are aware of the possible consequences, in the form of social and economic distress, when too many young people believe that their future is compromised. Still, governments have struggled to develop effective responses-or even to define what they need to know.’

In their report “Realising Talent: employment and skills for the future“, published in July 2014, The Centre for Economic Inclusion gave a definition of this problem for the UK.

“The consequence of not meeting this challenge by 2022 will be:

“9.2 million low skilled people chasing 3.7 million low skilled jobs – a surplus of 5.5 million low skilled workers with an increasing risk of unemployment

“12.6 million people with intermediate skills will chase 10.2 million jobs – a surplus of 2.4 million people

“Employers will struggle to recruit to the estimated 14.8 million high skilled jobs with only 11.9 million high skilled workers – a gap of 2.9 million.

“This could restrict economic growth if employers cannot recruit the skills and capabilities they need. We have calculated that in 2022 between 16% and 25% of growth could be lost by not investing in skills. This means that up to £375 billions of output is at risk.”

What if we could solve this problem, not only in the UK but also all over the world by building a skills-based vocational education system driven by learners’ needs, make it self-funding and infinitely scalable?

Here is what Max Hoefeijzers the man who created a solution for this supposedly impossible task has to say about it;

An example of a new type of FE college

“In the early 90’s youth unemployment in the Netherlands was at 30%, and a dropout rate in vocational education of between 30% and 50%.

“Dordrecht is in an area of 250 sq. kilometres with 300,000 inhabitants. At the time the college opened, it was an old industrial area with a poorly educated population where, since the early 20c, 45% of the working population had worked in shipbuilding and steel works.

“The region had high youth unemployment, low skills and had a deep-seated negative view of education. Many young people in the area considered themselves to be at the ‘bottom of the labour pile’ and had a negative view of education from which they just wanted to escape as soon as possible.

“Intrinsically connected to this, was a job shortage of technically trained personnel at mid and higher levels.”

Max Hoefeijzers and his team took over The Da Vinci College in Dordrecht, in 2004 creating a new learning environment designed according to the principle of living, learning and working.

Construction started in 2004 with a budget of €180 million, partly funded by the Da Vinci College, local government and commercial investors, such as property developers, building companies, investment funds and local businesses.

The innovations were many

- Housing learners on campus in their own accommodation with a social contract that rewarded them if they continued to study successfully

- Buildings which were built by local businesses or developers and rented to other businesses producing revenue

- Using the assets of the learning environment to borrow on commercial loans from banks

- Using the revenue to fund teacher’s salaries from the local education department

- Using social housing grants to develop property and facilities

- Offer reduced rentals to public services like the fire service to induce them to relocate and then pay rent towards developing the campus

Significantly, all the buildings and future developments have a relationship with learning because they provide construction internships for students undergoing vocational training at Leerpark.

The architecture and building standards are of a very high quality and the large campus has retained an intimate and cosy feel. Before the redevelopment, the old schools were poorly maintained and were covered in graffiti, the new Leerpark buildings look brand new after nearly 10 years of use.

A survey amongst students showed that buildings contribute to feelings of being valued and secure, and by making students communally responsible for the learning environment, individual ownership and motivation increase.

The principle of integrating learning into the fabric of the site extends beyond its construction and buildings. Learning and work areas are not classrooms, but real places of employment, bringing state of the art professional best practice into the vocational courses.

There is a hairdresser, a shop, a garage, a restaurant, a fire station, a department in a hospital and a sustainable factory, or FABLAB, (built on the same principles as Massachusetts Institute of Technology), which cost 10m euros.

Notably, the FABLAB is oversubscribed and has paid for itself in 10 years!

Living on campus is part of students’ personal development and the direct reward of living in a beautiful new apartment in return for continued achievement and progress in training is a powerful tool to create motivated responsible citizens working for their own futures in their local communities.

The courses are competency-based and assessed by government standards for vocational qualifications in conjunction with employer’s assessment criteria.

The two unique components are that the student can find their own path through the course by carrying out tasks for companies in any order required by real workflow governed business requirements.

The assessment of skills is then matched against the curriculum standards and statements, so the learning paths can be personalised for each student and company commercial situation.

The most successful experiment was making a three-sided rotating floor for football stadiums.

Students from a technical university, higher education, and vocational education worked together managed by staff from the contracting company to deliver the project.

Science students developed the concept of a floor for football stadiums that has three surfaces, grass for football, a hard floor for concerts and events, and when not in use for sport or entertainment, one side composed of solar panels to generate energy.

Higher education students produced the drawings and detailed calculations and the vocational students made the prototype and then worked together on the prototype testing and final modifications.

This example perfectly illustrates how learning is conducted at Leerpark. Students learn cooperatively to develop individual and team skills in multi-level learning spaces and real business tasks. You can also see how the courses are integrated with commercial projects companies and how students following their own learning paths.

Multinationals and small local companies are all involved like L’Oréal, Siemens, IHC Holland Shipbuilding, Krone Altometer, Damen Shipyards.

The core pedagogical principles are

- A real-life learning situation with real jobs, real customers, time pressure and real money ensuring that the student does not want to disappoint the customer and does everything to ensure the success of the mission

- The philosophy of acknowledging and building on the successes and developing competencies of the student increases their motivation to continue. The student is encouraged to take responsibility for creating their own curriculum and to reflect on the learning process, which focuses them on achievement

- There is no timetable

- Learning paths are coordinated so students can take skills acquired to new courses or higher education.

What are the results

12 years later

- 14,000 students have been through its gates since it started

- Employment rates from courses are 97%

- Local employers list Leerpark as their preferred source of talent

- The student dropout rate is still reducing and is less than 4%

- The local environment is now virtually crime free and property prices have increased

- 40% of students go on to higher education

- Rotterdam University has placed various departments on the campus

- The pedagogical model is now being tested to be replicated throughout the Dutch education system

So, what if we could replicate this model in the UK?

Could failing FE colleges be converted to this model to regenerate socially and economically disadvantaged areas?

Max Hoefeijzers is working on supporting similar initiatives in Holland where they are setting up pilot schemes in vocational education and schools to explore the integration of technical subjects and competency-based personalised learning paths.

How could it be done?

This successful model could be replicated in two ways.

Physically and as a cloud-based solution for existing FE colleges to plug into with minimum expenditure and disruption.

The experience and knowledge of Max and his team could be applied to a process inspired by Leerpark bringing interested parties together with a view to creating a public/private partnership.

A local national philanthropic organisation independent of government could act as a catalyst if their focus was innovating solutions in vocational training and could attract partners through its events and fellowship network.

Regions with the right economic and social profile of high unemployment, low skills and low land value located close to major conurbations could be approached with an outline regeneration plan and the Leerpark model as proof of concept.

The first stage would be promotional and exploratory involving discussions about local problems and showing examples of how the Leerpark model solved similar issues.

Stakeholders like local landowners, property developers, commerce, local authorities, local education departments and the community could be identified and approached.

My company, Vivagogy is developing an information system based on these principles and a consultancy model to deliver the knowledge exchange to build a project with this model.

We already have expressions of interest for a number projects including one or two in the UK.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could utilize this knowledge to solve one of the biggest education, social and economic challenges of the 21st century?

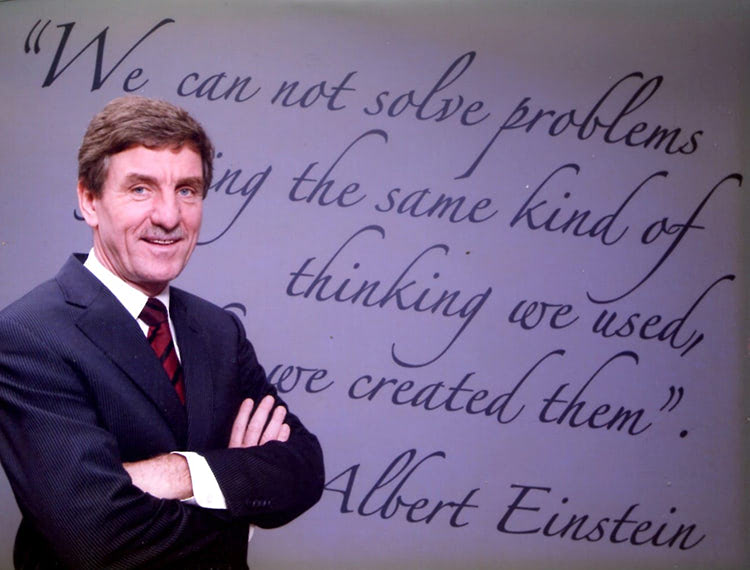

As you will see from the photograph above, Max Hoefeijzers used this famous quote by Einstein as his guiding principle.

‘We cannot solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.” Albert Einstein

Chris Heron FRSA, Cert Ed, CELTA, CEO of Vivagogy

For the last three years, Chris Heron has been researching education and learning models, including vocational education, around the world to build a new learning system.

His conclusion after three years is that further education is the solution to many of our most complex economic and social problems most notably youth unemployment and the skills gap.

Welcome to # Part 2 of a three-part series were Chris explains:

- What FE should be able to do, and why it is not doing it?

- What is the Dutch case study and why is it successful?

- How should FE work?

Responses