The Problem with Further Education and Apprenticeship Qualifications

World Skills Medal Winner, Plumbing Apprentice Dan Martins, is a shining example of what Further Education (FE) students can achieve. Indeed, FE offers many people chances to transform their lives and attain better wellbeing – so what is the problem?

2017 World Skills Medal Winner, Plumbing Apprentice Dan Martins

Behind this thin veneer of success and status in Further Education, there are some significant problems which could pose a risk to public health.

I attended a parliamentary hearing to give evidence as part of the Gas Engineer Training Standards Inquiry (GETSI). It was conducted by All Party Parliamentary Carbon Monoxide Group (APPCOG), which commissioned Policy Connect to conduct the research.

The inquiry is a response to a significant rise in reports of poor quality training of Gas Safe Registered Engineers.

My 2014 empirical study of full-time courses and apprenticeships in plumbing included observations of gas training in three mainstream FE Colleges and five workplace sites. The research showed significant problems with the quality of Further Education courses.

While my study celebrated the compassion and quality of FE teachers, it was apparent that they were under immense pressure to retain students and ensure they passed the exams.

Although many tutors liked online multiple-choice tests as a way to assess subject knowledge, others regarded them simply as memory tests. Many tutors doubted whether multiple-choice tests were suitable for testing the problem-solving skills and analytical abilities demanded of plumbers in the field.

Tutors were despondent at the process of allowing students to continually re-sit online assessments until they achieved the pass mark:

‘I think the online testing and keep on going back until you pass the exam is not a very satisfactory way of doing it.’ (Tutor Den College 2, cited in Reddy, 2014: 227)

There were structural pressures on tutors to meet externally-imposed targets and, judging from the majority of tutors’ responses, the credibility of the assessment process was highly questionable.

Indeed, teachers across the three college sites in my study were equally sceptical about the quality of practical plumbing assessments:

‘…there are a lot of tasks that are nothing to do with plumbing. Making a square of plastic pipe means nothing…there are a lot of board exercises, a lot of measuring, which needs to be done, but in those exercises there is nothing real about them. I don’t think you walk away from it thinking that you know a lot about plumbing.’ (Tutor Matt College 2, cited in Reddy, 2014: 155.)

Tutors in the study were unanimous in their judgements about college-based training and assessments failing to adequately represent the reality, problems and experiences of plumbers operating in the workplace:

‘College exercises in the workshop are not real-life exercises; they are simulated. Everything is nice and level and flat. There are no problems, it‘s all there. It‘s like I said, when you get into the real world and you get into someone‘s house, it’s completely different.’ (Tutor Darrel College 3, cited in Reddy, 2014: 156.)

While many of my findings in relation to the inadequacy of competency assessments support the existing literature on vocational education and training, my research brings about new insights in relation to health and safety.

My study reinforces growing concerns from the Gas Industry Safety Group (GISG) and the Institution of Gas Engineers and Managers (IGEM) (2016), who reported an increase in unsafe gas work by recently qualified engineers; from 1% to 5% (Gas Safe Register, in GISG/IGEM, 2016: 1).

They highlighted an over-emphasis on classroom theory and a dependency on online multiple-choice tests, with novices sitting gas safety exams who ‘were allowed to keep re-sitting the tests until they passed’, GISG/IGEM (2016: 20).

These findings build on the earlier work of the Unite Union (Unite 2012: 10), which stated that college-based courses can create ‘under-qualified individuals, who have the misconception that they are then able to undertake safety-critical work’.

Where did it go wrong?

In order to assess the deviation away from the original NVQ rules, it is important to understand the work of Gilbert Jessup, who was the Architect of UK competence-based qualifications.

Jessup (1991: 27) emphasised ‘the need for work experience to be a valid component of most training which leads to occupational competence’. Moreover, he asserted that occupational competence ‘leads to increased demands for demonstrations of competence in the workplace in order to collect valid evidence for assessment’.

However, the need for work experience has been ignored by awarding institutions for gas qualifications and other types of college-based full-time occupational courses. Owing to the findings in my empirical study, it has now become apparent that occupational competence assessments conducted in College contexts only lead to occupational competence in that particular College context – not the real world.

In consequence, nearly all practical assessments for plumbing, conducted in a College environment are invalid – this is because assessments cannot adequately accommodate variations between college and work contexts which may result in a significant variation in performance requirements. Jessup (1991:122) considered knowledge transfer problematic when variations in contexts existed.

Work and College present two unique social practices, and being in College requires a noticeably different behaviour, activity, performance and social interaction than is required in the real workplace (Reddy, 2014: 2017). For example, you may install a shower in College but not learn that, at work, there are job processes and technical issues, like knowing where to turn the water off. Similarly, there are health and social issues, such as respecting that people still need water to drink and to flush the toilet while the job is in progress.

Quality

Some of these problems in apprenticeship training were also reported more recently by the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR). Dromey, McNeil and Roberts (2017) argued that, in the absence of employer demand for skills, providers have come to rely on funding and regulatory systems set by a central government. In that case, the provision has been shaped by a government, rather than by employers and, according to Dromey et al, (2017:8) ‘it too often fails to meet the needs of either employers or learners, and labour market outcomes tend to be poor’.

These dubious qualifications are then administered with institutional convenience in FE Colleges e.g. delivering practical activities in the workshop and theory separated to a distant classroom (Reddy, 2014). It was stated in my study that such separations of subject matter allowed the college to get twice as many students onto plumbing courses because they spent more than half of their time in the classroom.

Thus, contexts for practical and theory learning of plumbing were separated. Though, it may be important to note that, on occasion, workshop models and simulations can be useful for tutors to explain theoretical aspects of the curriculum, but tutors report being unable to do so because workshops are typically oversubscribed.

In contrast, my study of plumbing training in Hong Kong (Reddy, 2017) revealed that classrooms for plumbing were always directly adjacent to the workshop, giving tutors the opportunity to create high-quality learning experiences for students. These involved hands-on skills training, modelling, high-fidelity simulations (good work replications) and theory-related activities, all of which were mediated by an expert tutor to help students derive meaning from practise.

This, of course, is also dependent upon having a meaningful curriculum design in College – the College may now become a place for apprentices to collaborate and share knowledge. Tutors can scaffold the relevant occupational learning, to underpin and extend apprentices’ competent performance at work.

However, the Further Education sector faces challenges in developing this type of learning culture because providers have tended to take simplistic economic approaches, delivering large numbers of qualifications at or below NVQ level 2. Ultimately, these qualifications offer poor labour market returns to students.

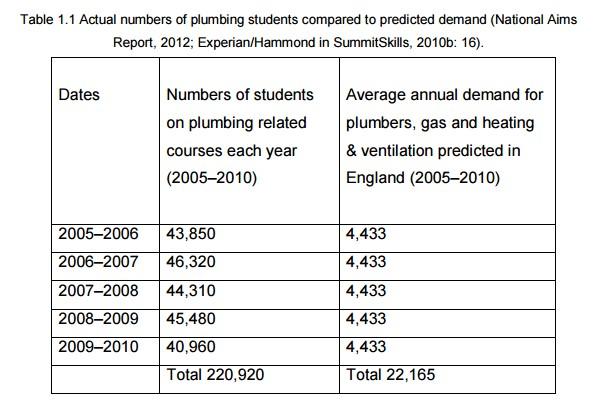

My empirical study of plumbing training revealed the real scale of this problem:

(Reddy, 2014: 23)

(Reddy, 2014: 23)

Along with the GISG/IGEM (2016) findings, the plumbing courses in my study were also theoretically biased and, with the (in)efficiencies in the assessment procedures, were economically beneficial to all the FE colleges concerned. Few tutors in my study had trust in the assessment procedures and methods – according to most of the tutors, the courses were detrimental to the students’ learning of plumbing and their welfare and opportunities for progression.

Tutors’ subjection to institutional pressures to participate in dubious qualification procedures, along with their above-cited unease about full-time plumbing courses for young people, led them to feel uncomfortable about the situation. The tutors’ doubts about the plumbing qualifications were further compounded by the poorly simulated nature of the practical curriculum and the invalid assessment methods – described by both apprentices and teachers in my study as ‘not real life’.

Such occupational assessments have left people working in the gas and plumbing industry with very little trust in the point, purpose and validity of the measurements.

With NVQs and competency courses, the assessment tasks were taken over by government-funded awarding bodies, which developed a complex hierarchy of assessors, and internal and external verifiers, in an attempt to guarantee quality – but now nothing could be further from the case.

Young (2011) argued that the old qualifications, prior to NVQs, were based on trust between people such as masters and apprentices and teachers and students. However, current competency qualifications do not create a basis for the same trust or quality.

In summary, the APPCOG inquiry into standards of gas engineer training will provide a much-needed snapshot of the problems with technical training and assessment, and possible ways of addressing them.

My next FE News article will discuss my evidence submission to the UK Industrial Strategy Commission in regard to ‘digital pedagogy’ and moving forward in Further Education with valid methods of Apprenticeship training and assessment.

Dr Simon Reddy, Education Professional and Master Plumber, leadinthewater.com

Follow Simon on Twitter: @reddyplumbing

References:

Dromey, J., McNeil, C. and Roberts, C. (2017) ‘Another Lost Decade? Building a skills system for the economy for the 2030s, Institute of Public Policy Research’, [Online], https://www.ippr.org/files/2017-07/another-lost-decade-skills-2030-july2017.pdf [30 Jan 2018].

Gas Industry Safety Group and Institution of Gas Engineers and Managers (2016) ‘Gas Engineer Training Report’, [Online], [20 Feb 2017].

Jessup, G. (1991) Outcomes: NVQs and the emerging model of education and training, London: The Falmer Press.

Reddy, S. (2014) ‘A study of tutors’ and students’ perceptions and experiences of full-time college courses and apprenticeships in plumbing’, University of Exeter PhD thesis, [Online], [10 Nov 2016].

Reddy, S. (2017) ‘World Plumbing Council Scholarship Report: A comparative education study of plumbing and training: Hong Kong and England’, [Online], http://worldplumbing.org/assets/uploads/2016/11/2015-WPC-education-and-training-scholarship-report-Simon-Reddy.pdf [30 Jan 2018].

Unite (2012) ‘Unite the Union response to the Department for Business, Innovation & Skills and Department for Education – Richard Review of Apprenticeships’, Executive summary, [Online], [2 Nov 2012].

WorldSkills (2017) ‘Image Dan Martins’, [Online], [29 Jan 2018].

Young, M. (2011) ‘National Vocational Qualifications in the United Kingdom: Their origins and legacy’, Journal of Education and Work, vol. 24, nos. 3-4, pp. 259-282.

Responses