Women, employment and childcare

Expanding Childcare: Time for children, parents and family learning

More working women

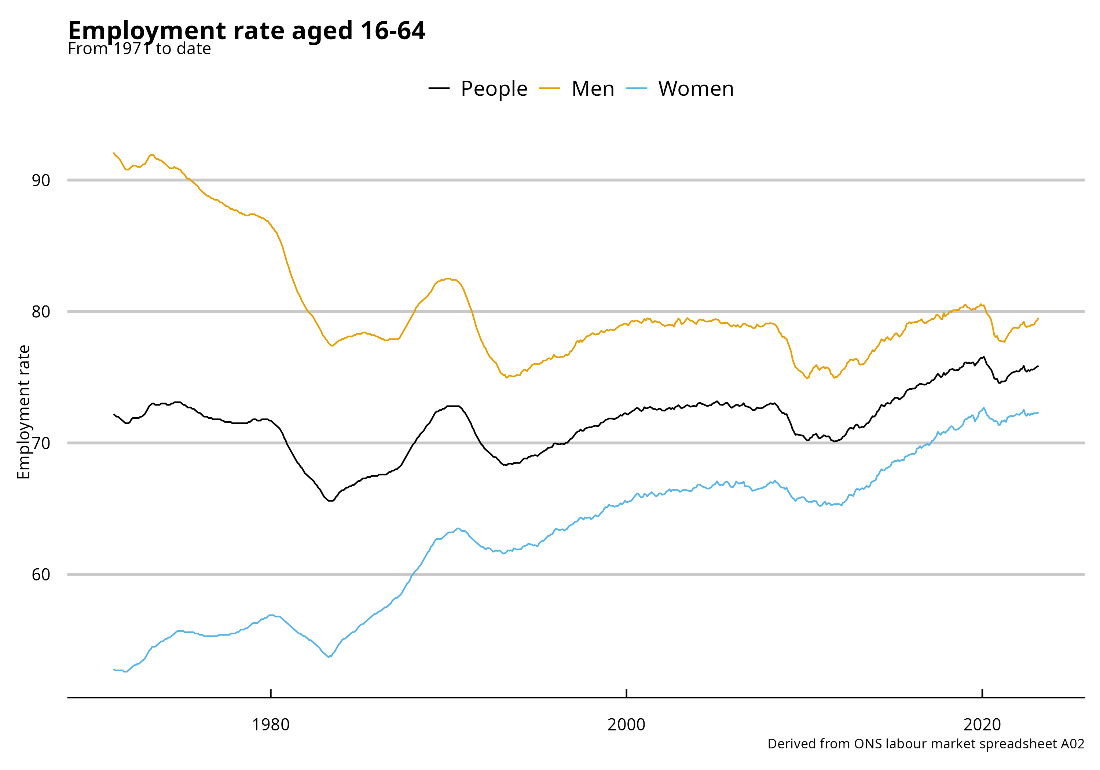

A major social change in Britain has been the re-entry of women with children into the workforce. In 1971, when data was first collected, the female employment rate was 53%. By 2023, it had increased to 72% (see Chart 1). Some 15.7m women are in employment today.

Chart 1

Source: Derived from ONS labour market spreadsheet A02

Households with dependent children

There are 8.24 million households in the UK with dependent children aged 0-18 (see Box 1 for definitions). This is the highest number since these figures were first produced in 1996. They are divided into three groups:

- 59.7% of households with dependent children are working households with all adults in work. This is below, but close to, the highest ever figure. It reached 60.8% just before the pandemic.

- 32.1% of households with dependent children are mixed households with both working and non-working adults.

- A further 8.2% of households with dependent children are workless households with no adults working.

Box 1

| Working and Workless Working means working for at least one hour. Workless means not working even for one hour. Some people who are actually not working are counted as working if they have a job to go back to. A key group for childcare policy is parents on maternity leave and paternity leave. Household Household includes all those living at an address. However, this means there is a very confusing implication: single parent households can be ‘mixed households’ – at least one working – if the household includes a single parent and one or more non-dependent children, with one (or more) working and one (or more) not working. Dependent Children Dependent children include all those under 16 and those 16-18 in further education. Those who are either in employment (but not learning) and those who are NEET get classed as non-dependent, as well as those over 18. So, the age range for children goes up quite a long way. Full-Time and Part-Time Working Full-time working is defined as 30 hours or more per week. Part-time working is defined as below 30 hours per week. |

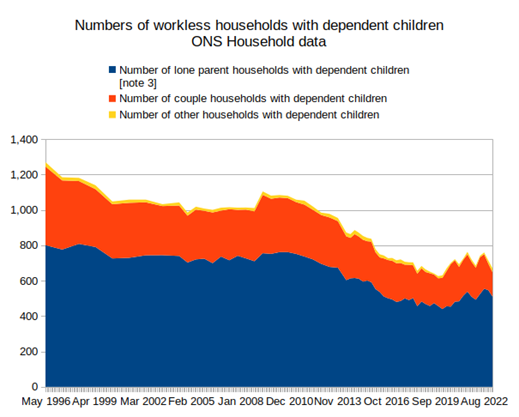

Workless households

The number of workless households is now 669,000 (see Chart 2). This is up from the pre- pandemic level of 626,000 but close to the all-time low. Of these:

- 600,000 are workless couples with dependent children, and

- 69,000 are workless lone parents with dependent children.

Employment patterns for women by dependent children by age of child

Rates

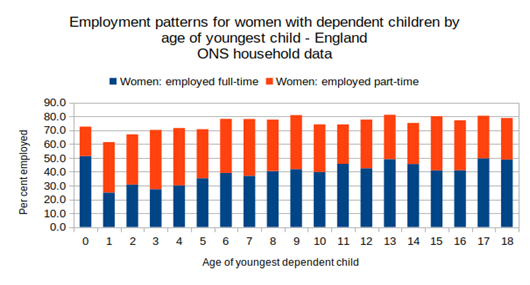

The employment rate of women with dependent children does not fall below 60% (see Chart 3).

For those with a youngest child aged 3 and 4 – where entitlements to free childcare of 15 hours per week for all children, and 30 hours per week for most working parents – the employment rate is 70%.

For those with a youngest child aged 2 – where some parents are entitled to free childcare of 15 hours per week – the employment rate is still 68%.

For those with a youngest child aged 1 – where there are no childcare entitlements – the employment rate dips but only to 60%.

The employment rate of women with dependent children does not fall below 60% (see Chart 3).

For those with a youngest child aged 3 and 4 – where entitlements to free childcare of 15 hours per week for all children, and 30 hours per week for most working parents – the employment rate is 70%.

For those with a youngest child aged 2 – where some parents are entitled to free childcare of 15 hours per week – the employment rate is still 68%.

For those with a youngest child aged 1 – where there are no childcare entitlements – the employment rate dips but only to 60%.

Chart 2

Source: ONS Release – Working and Workless Families 2023

Chart 3

Full-time and part-time working

In terms of women with a youngest child at age 4 and below, more work part-time than full-time (see Chart 3), although this simply means more work below 30 hours per week.

The high proportions of women working part-time (less than 30 hours per week) with the youngest child aged 5 and over relates at least in part to lack of wrap-around and holiday care. In turn, this impacts on the careers of women and gender pay gaps of women who have children.

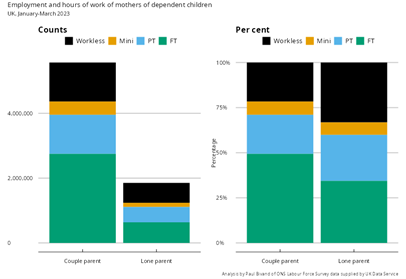

Hours worked by women with dependent children

Turning to hours worked by women (see Chart 4), they can be grouped into three categories:

- Full-time jobs: 30 hours or more

- Part-time jobs up to full-time jobs: between 16 hours and 29 hours

- Mini-jobs up to part-time jobs: up to 16 hours.

Chart 4

Source: LFS Dataset, January-March 2023 UK Data Services

Mothers with dependent children on benefits

An important factor in mothers’ consideration of working or not working is the policies of the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) towards benefit claimants. The extent to which parents will be affected by this depends on their family circumstances, but the DWP benefit rules are that parents should usually be working, with very limited exceptions.

The only group of parents that have no work requirements in Universal Credit are those with a child under the age of one.

If they have a child aged 1, they are expected to attend meetings to plan for work.

If they have a child aged 2, they are expected to prepare for work. This includes attending, and co-operating with, work-focused interviews.

Parents caring for children aged 3 or over must search for work, or more work, if the family earnings are below £617 a month (for lone parents) or £988 a month (couples). This is 15 hours for the lone parent and 24 hours for couples (across both parents) at the National Minimum Wage.

Tougher conditionality

DWP has previously reacted to DfE expanding childcare by increasing conditionality on parents to work if free childcare places are available. The 15 free hours for 2-year-olds from April 2024 may mean parents will be subject to work requirements up to that level, with similar changes when the planned free places from 9 months child age occurs.

Paying the childcare element of Universal Credit in advance

DWP funding for childcare (while working) has now been extended so that it can be paid in advance rather than arrears (a big issue in low-income families) but is not 100% of childcare cost. It is up to 85%, with a cap.

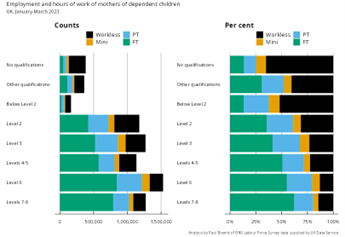

Qualifications for women by dependent children by age of child

Employment rates of mothers step up with each level of highest qualification, with those with no qualifications and those with below Level 2 having employment rates below 50% (see Chart 5).

‘Other qualifications’ in ONS are those that have not been given a formal equivalence, including a range of overseas qualifications. Employers seem to place these between Level 1 and Level 2, on average.

Overall, however, the numbers of mothers with qualifications below Level 2 are low. On the other hand, there are substantial numbers of workless mothers with high qualifications.

Chart 5

Source: LFS Dataset, January-March 2023 UK Data Services

The number of workless mothers with no qualification is 250,000 (200,000-300,000 confidence interval) in the UK. Those with below Level 2 are between 60,000 and 110,000, and other qualifications between 110,000 and 180,000. The numbers with Level 2 are between 320,000 and 420,000.

The relatively small number of mothers with low qualifications is likely to relate to the pressure on schools and colleges over the preceding period to ensure people have at least a full Level 2. The employment disadvantage for the small remaining group persists.

Recommendation 1

DWP should enable parents on Universal Credit, who must plan or prepare for work, to choose forms of skills training that they think would best help them to get jobs that are paid enough to claim in-work Universal Credit or not claim Universal Credit at all.

Recommendation 2

DWP should enable claimant parents to undertake the skills training they need to help them get better-paid work to better combine work and caring.

Recommendation 3

DfE and DWP should recognise that parents of school-aged children are time constrained and combine careers with childcare, and that a vision for wrap around childcare is needed.

By Paul Bivand, Independent Consultant

Campaign for Learning has released a new series of articles, Expanding Childcare: Time for children, parents and family learning.

See below when each article will be published on FE News:

Part One: Childcare the welfare state – 20th July

1. Will Snell, Chief Executive, The Fairness Foundation

Childcare and a new social contract

2. Anneka Dawson, Head of Pre-16 Education, Ceri Williams, Senior Research Fellow, and Alexandra Nancarrow, Research Fellow, Institute for Employment Studies

The childcare sector: Providers and the workforce in England

Part Two: Childcare and time for work – 21st July

3. Paul Bivand, Independent Policy Analyst

Women, employment and childcare

4. James Cockett, Labour Market Economist and Claire McCartney, Policy Adviser, Resourcing and Inclusion, CIPD

The planned childcare entitlements and progression into work

5. Jane van Zyl, Chief Executive, Working Families

Combining flexible working and childcare to solve the childcare crisis

Part Three: Childcare and time for child development – 24th July

6. Janeen Hayat, Director of Collective Action, Fair Education Alliance

Improving childcare quality to support educational outcomes

7. Megan Jarvie, Head of Coram Family and Childcare

Making a step change to child development through childcare

8. Professor Elizabeth Rapa and Professor Louise Dalton, University of Oxford

Childcare, children’s development and education outcomes

Part Four: Childcare and time for parental engagement – 25th July

9. Lee Elliot Major, Professor of Social Mobility, University of Exeter

The childcare revolution: A new opportunity for parental partnerships in child learning

10. Bea Stevenson, Head of Education, Family Links the Centre for Emotional Health

Childcare and parental engagement in child learning

Part Five: Childcare and time for adult skills – 26th July

11. Simon Ashworth, Policy Director, AELP

The new childcare entitlements and skills bootcamps

12. Sharon Cousins, Vice Principal, Newham College and National Association for Managers of Student Services Executive

The new childcare entitlements and access to further education

13. Susan Pember, Policy Director, HOLEX

A thriving society means linking the new childcare entitlements to adult learning

Part Six: Childcare and time for family learning –

27th July

14. Sam Freedman, Senior Fellow, Institute for Government

The childcare revolution and family learning

15. Susan Doherty, Development Officer – Family Learning, Education Scotland

Family learning and childcare: Lessons from Scotland

28th July

16. Susannah Chambers, Independent Consultant

Bringing childcare and family learning together

17. Henriett Toth, Parent

Family learning and childcare: A personal experience

Responses