Mending the Gap: Are the needs of 16-18 year olds being met?

At a time of great political and economic change following the decision to leave the European Union there is widespread recognition that the need for a workforce equipped to operate in a high skills economy has never been greater.

Changes to the qualification structure including the introduction of new T Levels, reform of the funding of apprenticeships with the introduction of an apprenticeship levy and legislation to increase the diversity of the higher education sector are collectively expected to play a major part in making this a reality.

It is therefore more than ironic that young people aged between 16-18, about to enter the workforce at this crucial time, who should be expected to be at the heart of any strategy, remain neglected, under resourced and at the mercy of volatile policy change with every change of government.

A significant proportion of young people still find their needs for the education and training provision which is right for them unmet and their voice unheard.

The often-quoted sub text of the Kennedy Report in 1997, ‘If at first you don’t succeed, you don’t succeed’ risks remaining true for too many 16-18 year olds.1 It was not intended to be so.

At age 18 after participating in education and training, young adults would be ready to progress into higher education – typically full-time – a job with an apprenticeship, part-time vocational education or skilled employment.

Enabling young people to continue in education and training

Successive governments have turned a blind eye to the participation age, focusing instead on a smaller group of 16-17 year olds who are ‘not in education, employment or training’ (so-called NEETs).

They have also looked away from the need to enable young people to continue in education and training – especially full-time education – until the end of the academic year when they reach 18. A gap still remains and it must be mended.

Over a decade ago, the then government announced that the age of participation in education or training was to be raised. The time is now right to review the impact of increasing the participation age to the 18th birthday and indeed to go further and extend it to the end of the academic year in which they turn 18.

Such a review will cause Westminster and Whitehall to evaluate what needs to be done to ensure a full range of education and training opportunities are available to the 66% of 18 year olds who do not enter full-time higher education and the 50% of 18-30 year olds who do not do so.

The history of participation until the 18th Birthday

In 2007, the then Secretary of State for Education and Science Alan Johnson announced in a Green Paper ‘Raising Expectations: staying in education and training post-16’ that the age of participation in education and training should continue until the age of 18. This was confirmed by legislation and was widely referred to as ‘Raising the Age of Participation’ or RPA.2

Participation was tightly defined, with only three alternatives identified as satisfying the requirement. They were Full Time study, Full Time employment with training, or an Apprenticeship.

No other options such as study on a less than full time basis, jobs without training or remaining inactive were to be permitted, with very few exceptions.

Significantly, the Labour Government planned a range of enforcement measures on 16 and 17 year olds to participate and on employers to offer jobs with training but these were not introduced.

The Coalition Government confirmed its support of the policy in 2011, stating ‘We owe our young people the very best support on their journey from school or college into the world of work’.3

The ‘compulsory’ age of participation was raised to the eighteenth birthday in September 2015. However, accountability for the success of the policy was kept deliberately vague. Overall strategy remained with the central government department whilst local authorities were responsible for compiling participation data and supporting measures to increase participation but from existing budgets.

This was alongside their existing duty to monitor those young people ‘Not in Employment, Education or Training’ (NEET). Other government agencies including the then Education Funding Agency were also to play their part. Again, no enforcement measures and no additional overall coordination were introduced.

This inevitably led to confusion over which young people are covered by the RPA policy and those who are considered NEET.

The majority Conservative Governments led by David Cameron and Theresa May have followed in the footsteps of the Coalition. The result is an uncertainty where ultimate responsibility and accountability for the success of the RPA policy lies.

Assessing participation to 18

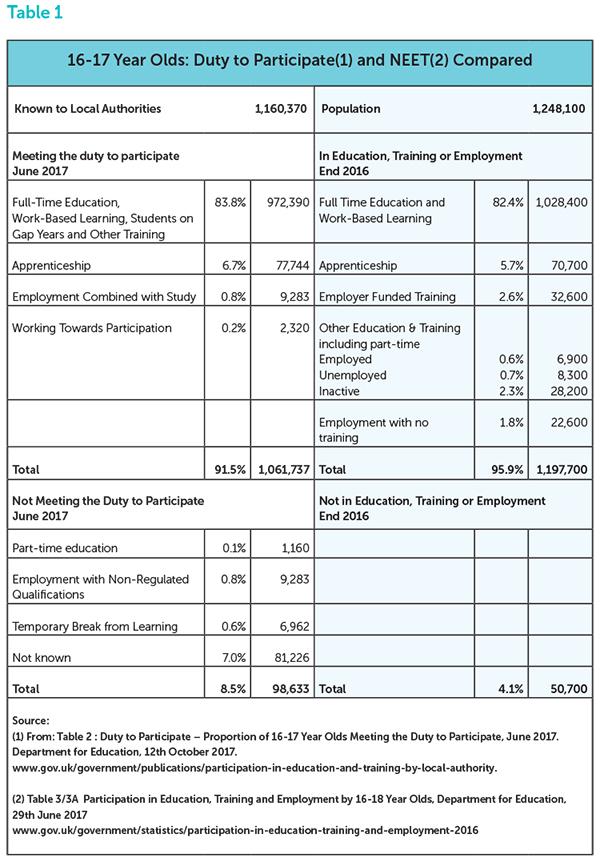

As indicated above, it can be very easy to confuse measurement of success in RPA with measures of individuals who are NEET. For example, the duty on local authorities to provide participation data is well monitored.4

From the data available for July 2017, it would appear that 8.5% of 16-17 year olds are not participating, equating to around 99,000 individuals. However, the definition applied to membership of the NEET group is not the same as that applied under RPA. As indicated above, the RPA criteria are specific and allow only three prescribed types of participation.

The definition of NEET includes these but also covers any type of employment, full or part time, and any participation in education, again on a full or part time basis. In measuring NEETs, the emphasis is clearly on participation alone, including participation with non-regulated training (which may not lead to a recognised qualification).

This wider definition means that there is no effective measure of the success of RPA, other than to conclude that nearly 100,000 young people are not involved in activities which would satisfy the RPA criteria. Given the more rigorous definition under RPA, the real figure is undoubtedly higher (see Table 1).

The table is based on statistics prepared by DfE to illustrate compliance with the RPA duty and data collected from local authorities to measure NEETs.

It has been amended to include a calculation for the ‘Not known’ category assessed by local authorities. It can be seen that although the two ‘mainstream’ pathways, Full Time Education and Training, and Apprenticeship, engage just over ninety per cent of the group, with a further one percent on other provision within the RPA measures, eight and a half per cent of the cohort still remain uninvolved, with a relatively large number of ‘Not knowns’, quantified to around 99,000 individuals.

The disparity between the measure of NEET used in the second comparison table and the measure of compliance with the RPA Duty used in the first could not be more marked. It clearly illustrates that achievement of the latter has proved to be far more difficult than envisaged and in many respects has not advanced in the last ten years.

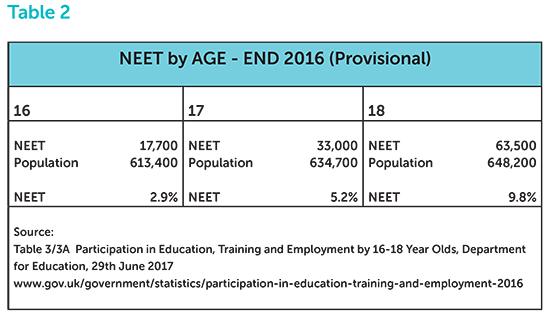

To be fair, it seems that the participation age has had some relative success in reducing the number of young people considered NEET at age sixteen but there is almost a doubling in the subsequent year at age seventeen, a pattern which is repeated in each successive year (see Table 2).

It is not unreasonable to conclude that despite the success in persuading the vast majority of 16 year old school leavers (and their parents) that continued participation is required, it soon becomes apparent either because of the lack of opportunities or the lack of enforcement young people are increasingly unable or unwilling to participate.

Even so, this measure of young people who are considered NEET appears to offer some comfort that RPA has worked at least in the first year. However, this may be misleading. Too many young people may still find themselves in jobs with little chance of developing worthwhile skills or gaining recognised qualifications.

Although successive governments have shown proper concern at the number of young people classified as NEET, the more demanding challenge set by the original RPA legislation has not been monitored with the necessary rigour and may not have been achieved.

Although successive governments have shown proper concern at the number of young people classified as NEET, the more demanding challenge set by the original RPA legislation has not been monitored with the necessary rigour and may not have been achieved.

Given that the ambition of RPA was to ensure not only that all young people were engaged, however worthy an aim that might be, but that they be engaged in one of the three prescribed high quality pathways, more must be done to establish the true baseline and then devise strategies to make the promise of RPA a reality for all. The difficulties in establishing accurate data have been identified above.

They are further complicated by the lack of a clear recognition that 16-18 represents a phase of education in itself, where the constraints of the school curriculum are removed but, in theory at least, the requirements and duties of RPA must be followed. Much of the available data either ignores the RPA criteria or uses other definitions of participation such as 14-19 (e.g. for University Technical Colleges) or 16-25 (for participation data and NEETs).

Young people aged 16-18 years have often found themselves at the centre of short lived educational reforms, with high aspirations but only partial impact. RPA is one of those and has been compounded by additional shortcomings in student funding, transport and support for issues such as mental health.

The time is right to review not the underlying principle of RPA which remains as valid and necessary now as it did eleven years ago, but the effectiveness of the measures in place to make it a reality.

The rise in NEET at 18

For many young people, this final phase of compulsory participation can be the last chance for them to build firm foundations for their future lives and careers. It is also potentially the last time when a cost-effective intervention can be expected to succeed, as once the compulsory phase has ended, tracking individuals and their progress becomes increasingly difficult.

The increase in NEET for every year post 16 provides a clear illustration (see Table 2). In addition to the rise in NEET by age 18, we also know that too many young people do not achieve a Level 3 by age 18. By age 18, just under 50% still do not have a Level 3 – the minimum to boost productivity and earnings – and even by age 19 40% do not do so. Furthermore, by age 18, nearly one in five do not have a Level 2 and this only falls to one in six at age 19.5

What needs to be done

If we are to equip all our young people to meet the challenges ahead, four things need to be done:

- the duty to participate should be extended to end of the academic year in which a young person turns 18

- in parallel funding needs to made available to allow providers to deliver high quality provision for all pathways – full-time academic and technical education, and apprenticeships offered by levy and non-levy payers until the 19th birthday

- financial support must be extended to enable 16-19 year olds to participate in full-time education and apprenticeships until their 19th birthday, and

- sanctions should be introduced as a last resort to ensure young people and parents support the duty to participate, not to criminalise young people – as the intention is not to get to that stage – but to ensure cases of non-participation are highlighted to Ministers to stimulate the necessary policy change to offer young people the opportunities they deserve

To do right by our young people we will need to widen the opportunities available alongside the introduction of sanctions to enforce participation, with an emphasis on the former in the short-term and the latter in the medium-term.

A single statement of duties and responsibilities

Young people, parents, teachers and prospective employers need to know the nature and extent of their entitlement. A single statement of the duties, responsibilities of all parties is essential for clarity and accountability.

Communicating the existing free tuition entitlement to young people to 19

More will be said about levels of funding to providers in the next paragraph. However, it should not be forgotten that tuition fees for young people in the RPA group are not charged. Apart from the need in most cases to pay for any costs of travel, courses are ‘free’.

Study after the age of 19 is likely to require the individual to find at least some of the funding required. This makes it even more important to ensure that young people are fully aware of the consequences on non-participation for their future careers and the likelihood that they will have to pay via loan or other means for any qualifications they wish to pursue later in life.

More must be done to get this message across to young people and parents. The year on year doubling of the NEET group shown above suggests that different measures are required for those who become disengaged after leaving school. Difficulties can arise in tracking individuals, even in determining residence.

These problems increase with each succeeding year, as do the costs of re-engagement. Effective intervention during the RPA phase is the most cost effective solution for young people and for the state.

The price of success: fair funding for 16-18 year olds to providers

Nothing can be achieved without the funding to do it. Young people aged 16-18 are discriminated against compared with pupils in secondary education up to the age of 16 (Key Stage 4) and students studying full time at a university on completing education at 18.

In the case of the former, core funding amounts to £4,800 per pupil, plus additional allowances for students from challenging backgrounds (including Pupil Premium funding).

Although a matter of growing contention, most universities have chosen to set a tuition fee at the maximum level of £9,000.

In contrast, core funding for 16-18 year old students whether in school sixth form, further education college or sixth form college is set at £4,000, a sum which although guaranteed in cash terms to 2020 represents an real terms reduction in funding when taking into account other unavoidable inflationary pressures and employers costs.

The situation is compounded when the reduction in funding of 17.5 % following the student’s eighteenth birthday is taken into account.

Although not covered by RPA duties at the moment, many of the young people who have been least successful at school require more than two years to reach their highest standard.

A significant proportion will have continuing additional needs which although not necessarily triggering formal additional support funds demand additional expenditure on the part of the provider.

This will include those with continuing support needs to develop literacy and numeracy and also young people whose education has been affected by health issues, including mental health.

Given that RPA sets a new higher limit for compulsory participation, young people engaged in RPA activities should be treated fairly and with providers delivering provision to 19 year olds funded at least the same level as those under sixteen.

A curriculum for the future: ensuring a skilled and motivated workforce

Level 3 T Levels are unlikely to help those not meeting the duty to participate

Reform of the vocational education system has been a focus for successive governments. The main driver has been a desire to provide clarity for young people, employers and policy makers. One unfortunate result of this has been to subject successive generations of 16-18 year olds to new qualifications and structures which have often been untested, introduced at short notice and short lived. They have included a multiplicity of awarding bodies competing for the same groups of learners offering essentially the same qualifications, a range of new qualifications such as General National Vocational Qualifications, Diplomas, Applied General awards as well as further changes to GCE A Level.

The recently concluded review of vocational qualifications led by Lord Sainsbury6 aims to provide some much needed clarity around the issue, with the proposal to introduce new ‘Technical’ Levels (T Levels) in a range of disciplines. There is also the promise that the vocational qualifications followed by a large number of 16-18 year olds will be afforded the same recognition and value attached to established academic pathways, principally A Level. Welcome though this may be, a number of questions remain to be answered.

Not all vocational disciplines are covered by the proposals raising questions about what will be the future for qualifications in these areas. Perhaps of more structural significance is that T Levels will only be offered at Level 3 (equivalent to A Level).

Critically, whilst T Levels at Level 3 might offer more choice for those able to follow a Level 3 route at 16, many of those not meeting the duty to participate will struggle to achieve a Level 2 by age 19.

Beyond the Transition Year

Many young people leave school at sixteen without the examination success needed to study at Level 3. For some, the academic school curriculum has not allowed them to acquire the practical or applied skills they have the potential to develop, whilst others seek to enter the world of work at the earliest opportunity. Proposals for a ‘transition’ year to meet the needs of these young people have yet to be worked out in any detail.

It would be unfortunate if uncertainty or delay led to poorly thought out provision for a group of students most at risk of failing to meet the requirements of RPA and most in need of additional support and guidance. Since the transition year is about assisting 16 year olds to be able to join a Level 3 T level later on in their 16-19 career, it might not assist those 16 year olds who will do well to achieve a Level 2 by age 19.

The decision by DfE to review Level 2 and below provision for 16-19 year olds is, however, to be applauded and must be used to good effect.

Alongside this review, DfE should conduct an analysis of the highest level of qualification held by 16 and 17 year olds not meeting the duty to participate.

It is likely that many of those failing to meet the duty to participate do not have a Level 2 qualification by age 18 given that 20% of 18 year olds have not obtained this level of qualification.

With T Levels set at Level 3 – and the transition year positioned as assisting 16 year olds who have the potential to achieve a Level 3 by age 19, there is a danger that the reforms to technical education for young people, important and welcome as they are, might not help 16 and 17 olds not in education and training to achieve the basic minimum of a Level 2 by age 18.

It is crucial that the same amount of political interest in developing Level 3 technical education for 16-18 year olds is applied to young people needing to participate to achieve a Level 2 by age 18.

Competition between Level 3 T-Level work placements and Level 2/3 apprenticeships

It may rightly be argued that any vocational education system worth the name should contain not only the knowledge and personal development to produce effective members of the workforce but also experience of the real world outside school or college. This is essential to develop those skills which cannot be acquired inside the classroom.

These include most of the attributes sought after by employers, including punctuality, team work, initiative and resilience. The proposals for the new T Levels include a significant element of work experience, amounting to over forty days. Whist this may appear to be a laudable objective, there are a number of potentially fundamental flaws in the approach. Consultation with employers appears to have been minimal.

It is thus not certain that in what promises to be an even more pressured time for businesses, they will have the time or capacity to make available the thousands of placements this will require. There may be differential geographical impact, particularly in rural and coastal areas where large employers may not have large scale operations.

Expecting the small and medium size enterprises which make up the bulk of most local economies to pick up the burden is challenging. Further resources will have to be devoted to establishing, managing and monitoring work experience schemes. Given the ambitions of T Levels, it will be necessary for placements to be in industries directly related to the area of study. In some, for example Construction or high tech manufacturing, there may be real commercial or legal restrictions which will prevent the placements giving participants the anticipated experience.

It also likely that the pressure to create placements will have an adverse impact on the availability of apprenticeship opportunities for younger people as employers are pressured to provide placements rather than apprenticeships. Opportunities for students especially those at Level 2 may become even more restricted. This would surely be a negation of the underlying philosophy of RPA and the curriculum reforms heralded by the Sainsbury Report. By default, apprenticeship could only become a realistic option at eighteen and probably at higher levels.

Of course, this may be ultimately a desirable aim in an economy which aspires to be based on high skills and high productivity. It does, however, raise questions about the employment prospects of young people who choose not to follow an academic path and who will provide the backbone of skills at Level 2 and 3 still needed across all industrial and commercial sectors.

Alternatives to GCSE resits

The curriculum for 16-18 year olds is further complicated by the continuing requirement for those who did not pass GCSE Mathematics and English on leaving school at sixteen to work towards achieving that standard whilst studying post 16. This inevitably places a greater burden on young people who may have the highest of motivations to succeed in the vocational discipline of their choice but who see little relevance in repeating an academic qualification which they have failed at least once already. Not only does this represent poor value for money as demonstrated by the low levels of pass in both subjects, it also takes up time which could be spent acquiring the skills and knowledge needed in their chosen trade or profession. Whilst it cannot be denied that good levels of literacy and numeracy are essential for virtually all skilled professions, for students who have already made a choice of career, those skills are best fostered in a context recognisably relevant to that career. The experience of repeating failure perhaps on multiple occasions can be a major de-motivator, undermining confidence and leading to dissatisfaction amongst students at a crucial time in their career preparation. Robust alternatives to develop the required skills in context are urgently needed.

T Levels and GCSE resits

A further unintended consequence may be to restrict the opportunities for meaningful work experience for students undertaking the Transition year with the aim of entering employment at the earliest opportunity. No assessment has been made of the impact of a longer period of work placement on two other facets of the post 16 curriculum.

The preceding paragraph has set out some of the issues surrounding the policy of compulsory re-sits for English and Maths GCSE. It is likely that at least some students studying T Levels will need to take these examinations. A period away from school or college on work experience is unlikely to be helpful in maintaining continuity of study or assisting examination preparation. Finally, a number of students have part time jobs, often in areas unrelated to their chosen study either because opportunities don’t exist in those areas locally or service sector employment is more readily available on a part time basis.

The income generated by these jobs is often needed by less well-off families and young people are unlikely to sacrifice the income earned for an unpaid work placement which may not only require additional expenditure on transport but also put their existing employment at risk. It would be ironic if a policy aimed at making young people work ready discriminated against those who have the initiative to obtain employment alongside study, earning income and at the same time acquiring the very skills employers seek.

Developing our young people

The aim of the work placement component is to equip young people for employment with both the knowledge and the personal skills to make an early positive contribution in their chosen employment. If placements cannot be found for all students, there are other alternatives which, although not vocationally relevant (and work placement should undoubtedly figure across all programmes) can develop the same skills.

These include institution based realistic work environments which reflect not just the high levels of technical and specialist equipment needed (often described in the over used phrase ‘state of the art facilities’) but also the those of a modern working environment including ‘normal’ working hours including unsocial hours, robust quality control and industry relevant approaches to discipline and working ethos. The next section will consider aspects of the need for a broader curriculum post 16.

Participation in activities designed to encourage personal development in areas such as resilience, working with others, making a contribution to the community and taking responsibility are given scant attention in the assessment of post 16 Study Programmes and are often considered marginal.

This is despite the fact that employers’ organisations and individual employers consistently identify the lack of such skills as a major failing across all phases of our education system. At a time of radical curriculum review, the time is right to reconsider how these vital aspects of post 16 education can be placed at the centre of the offer, regarding young people less as empty vessels to be filled with skills and knowledge and more as young adults preparing for a future which will make demands on them to learn new skills, adopt new habits and solve problems in new ways.

Examples of the kinds of activity which should be given more weight include participation in community activities including school or college based fund raising or other charitable work, commitment to a structured scheme such as the National Citizenship Service, the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award Scheme or formal youth organisations. Credit should also be given for part time employment monitored against robust standards.

Supporting students to succeed: more than just skills and knowledge

The relatively low levels of funding applied to post 16 students has a number of consequences.7 In addition to the reduced contact hours when compared with other European countries,8 the pressure to achieve GCSE English and Maths further reduces time spent on the vocational elements which motivate many students to participate in the first place.

Inadequate funding also reduces the resources available for personal development activities which not only foster employability skills but also help to form the citizens of the future. So-called ‘enrichment’ activities have either been drastically reduced or disappeared altogether from the 16-18 curriculum.

Initiatives such as the National Citizenship Service whilst very welcome have so far failed to replace the vital elements which made a post 16 education more than simply passing A Level examinations or acquiring a set of skills. The qualities of maturity, confidence and resilience valued by employers are the same as those which make good citizens.

Expanding apprenticeships for the RPA group

In addition to the academic and vocational routes, young people also have the option to undertake an apprenticeship. Unfortunately, following the introduction of the apprenticeship levy, employers have shown a reluctance to offer apprenticeships to young people. Statistics published in November 2017 show a significant and continuing decline in the number of apprenticeships taken up by young people aged under nineteen years of age.

Whilst it may be too early in the life of the new levy system to reach firm conclusions, apprenticeship is the right choice for many young people. However, for them to succeed employers must be willing to provide the necessary jobs. That they are failing to achieve this ambition on leaving school is a serious flaw in the system which must be addressed.

The solution to the problem can only be found if employers, providers, funders and government make a concerted effort to not only promote the value of apprenticeship but to ensure that it has the necessary prestige and status to sit alongside the other RPA alternatives.

It should go without saying that young people choosing this demanding route should receive the same treatment in terms of support, access to benefits etc as their peers choosing to study full time. Most importantly of all the Treasury and the DfE must introduce a ring-fence to cover the 100% of the training costs of apprenticeships to all levy and non-levy payers wishing to take on 16-18 year on apprenticeships up to Level 3.

Maintaining benefit payments for apprentices

A further series of questions arise when dealing with young people choosing the apprenticeship route. The current difficulties in apprenticeship recruitment amongst this age group have been referred to above.

Although covered by the RPA umbrella, these young people are rarely considered when dealing with the broader issues affecting their full-time student peers. For example, the protections offered by Safeguarding procedures and Prevent apply equally to all learners, including apprentices.

Given the nature of some apprenticeships, for example those with small businesses, it is unlikely that the young people concerned will benefit from any structured personal development.

Young apprentices are likely to be paid at the minimum level permitted at least in the early stages of their career (currently £3.50 per hour). Coupled with the loss of any entitlement to family benefits which goes with an apprentices ‘employed’ status, the cost of essentials including transport can actively discourage young people from less well-off backgrounds from considering an apprenticeship.

Duties, responsibilities and entitlement: helping our young people to succeed

The original RPA policy was clear in its ambition to make sure that no 16-18 year old young person was left behind whatever their ability or aspiration. Exceptions were few and intended to reflect very special circumstances affecting a small minority of young people. It is therefore not unreasonable to view the RPA as entitlement for the target group, with consequential duties on that group but also on parents, education and training providers and employers.

The enforcement measures to be given to local authorities proposed in the original concept have not been enacted by any administration. It has been stated that the system is intended to positively support young people to participate rather than coerce. It is understandable that such measures should be seen as a last resort. Seeking to criminalise young people or their families is to be avoided, especially given the difficulty of taking such action with children under the age of sixteen.

The limited range of post 16 opportunities under RPA presents difficulties for enforcement, for example in situations where a young person wishes to undertake an apprenticeship but no vacancy exits with a local employer. Compulsory attendance at some form of full time education or training may be seen as an unsatisfactory alternative with even more difficulties of enforcement.

However, enforcement measures should still remain an option and used in those circumstances where a range of alternative provision is available even if that provision is not the individuals’ first choice, as in the circumstances outlined before. Without effective enforcement measures, the whole approach to RPA risks losing credibility.

Other measures short of court action could include more rigorous enforcement of benefit rules and continued engagement with projects aimed at hard to reach individuals and communities such as those available under the European Social Fund supported Youth Engagement Initiatives.

More positive actions could include removing the barriers to participation which currently exist, certainly for the around ten per cent of young people who currently fail to participate. These include better targeted advice and guidance, especially where parental support may be limited, financial support with travel to study or work and assistance in acquiring equipment and clothing needed for the chosen pathway.

Employers of young people on a full time basis but not following an apprenticeship are obliged to provide suitable education or training. This has not been enforced due to a wish to reduce bureaucracy and prevent any disincentives to employing young people in the first place.

Again, however laudable each of these objectives may be, the unintended consequence may be that the small number of young people following this route are further disadvantaged. Any training given may be short term in nature, necessary for compliance such as health and safety training or not transferable such as skills needed for a very specific low skill task. Given the apparent decline in the number of 16-18 year old apprenticeships and the availability of funding via the levy, employers choosing to go down this route should be obliged to place any young person employed for more than twenty hours per week on an apprenticeship programme wherever one of relevance exists.

Clearly, it would be both unrealistic and unreasonable to require employers to create jobs simply to provide opportunities for 16-18 year olds. However, the apprenticeship levy opens the door to an approach which can incentivise making at least some of the new job vacancies employers may have available to young people.

Provision for this group is already ‘free’ to the employer. Further incentives could take the shape of support with travel on public transport, wage compensation for supervision in the workplace (especially for small firms) or, for the young person, a completion bonus on achieving agreed milestones, including improvement in English and Maths attainment.

Afterword

The original intention for RPA as set out in 2007 was bold and inclusive. It recognised that while most 16-18 year olds would continue in some form of participation post 16, a hard core of around ten per cent would remain difficult to engage. Despite the efforts of the last ten years that ambition remains unrealised.

The challenges and opportunities post Brexit coupled with the need to sustain a high skill economy give the pressure to achieve an inclusive society an added economic imperative. Effective implementation of RPA must be one of the most important responses.

Once successful, and with successive generations of 16-18 year olds making an increasingly valuable contribution to the success of the nation, there must be a debate as to whether these vital and energetic young people should be given a real say in their futures by enabling them to take part in our democratic processes and vote.

John Widdowson CBE, Principal, New College Durham

About John: He began his career as a lawyer but has worked in Further and Higher Education for over thirty years, the last nineteen of which have been as Principal of New College Durham. The College was graded “Outstanding” by Ofsted in 2009. New College Durham is lead sponsor for two Academies in County Durham.

In 2011 the College became one of the first two nationally to be granted Foundation Degree Awarding Powers by the Privy Council. John is Chair of the Mixed Economy Group of Colleges and was President for the Association of Colleges from August 2015 to July 2016.

John has published papers and articles on a range of education subjects and has spoken regularly at national and international conferences, focussing in recent years on the challenges of widening participation in higher education and developing college based higher education.

John was appointed CBE in June 2010 for services to Further and Higher Education.

Author acknowledgements: Thanks to Mark Corney for his advice, support and enthusiasm in putting this document together. Any errors that remain and the opinions expressed in the paper are my own.

References:

1. Learning Works: widening participation in further education, Further Education Funding Council, 1997

2. Education and Skills Act, 2008

3. Building Engagement, Building Futures: Our Strategy to Maximise the. Participation of 16-24 Year Olds in. Education, Training and Work, HMG, December 2011

4. Level 2 and 3 attainment in England: Attainment by age 19 in 2016, Department for Education, Statistical First Release (SFR) 16/2017, 30 March 2017 SFR16_2017_V2.pdf

5. e.g. see Participation in education and training: local authority figures participation-in-education-and-training-by-local-authority

6. Report of the Independent Panel on Technical Education, Department for Education, April 2016 Report of the Independent Panel on Technical Education.pdf

7. Costing the sixth form curriculum, Sixth Form Colleges Association, March 2015 SFCA Costing The Sixth Form Curriculum(web version).pdf

8. The Structure of European Education Systems 2016/2017, European Commission Structure of education systems 2016 17.pdf

About NCFE and the Campaign for Learning Policy Papers: The purpose of this policy paper is to encourage debate on key issues for post-16 education, skills and labour market policy, They are intended to inform policy makers at Westminster, Whitehall and stakeholders in the education and skills system. This paper is the fourth in a series that examines current and emerging policy from a learning and skills perspective.

Previous papers are:

- Earn or Learn for 18-21 year olds: New Age Group, New Policies (November 2015)

- University or Apprenticeships at 18: Context, Challenges and Concerns (April 2016)

- Reforming Technical and Professional Education: Why should it work this time? (February 2017)

Responses