Investment in the round

The UK is in a period of stagnation, with our economy defined by the toxic combination of low productivity growth and high inequality. Years of underinvestment is one of the things contributing to the UK’s productivity slowdown.

If the UK is to escape this trend and become a richer, more productive and less unequal nation, we must reverse this trend and make the 2020s a high-investment decade.

We have explored these issues in more detail in the interim report for the Economy 2030 Inquiry – ‘Stagnation Nation’ – a collaboration between the Resolution Foundation and the Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics, funded by the Nuffield Foundation.

The UK is in a period of stagnation

The UK economy has been declining since the financial crisis. This has real impacts for people and businesses up and down the country. For example, labour productivity grew by just 0.4% a year in the UK in the 12 years following the financial crisis – half the rate of the 25 richest OECD countries, which saw growth of 0.9%.

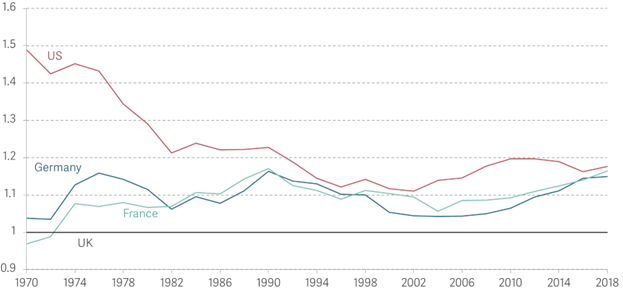

In Figure 1, we compare the UK to some countries we tend to think of as similar (the US, France and Germany). We see that while productivity in the UK was similar to France and Germany at the turn of the century, the UK’s relative performance has been declining since the mid-2000s.

This weak productivity growth has real implications for people’s wages; while real wages grew by an average of 33% a decade from 1970 to 2007, this fell to below zero in the 2010s. This meant that by 2018, typical household incomes were 16% lower in the UK than in Germany and 9% lower than in France, having been higher in 2007.

Figure 1: UK productivity has fallen further behind France, Germany and the US since the early 2000s

Ratio of GDP per hour worked compared to the UK, current Purchasing power parity (PPP)

(Notes: Data shown is two-year rolling averages. Purchasing power parity (PPP) is used to compare labour productivity between countries. PPP is a theoretical exchange rate in which you can buy the same amount of goods and services in every country. These data are current PPP rather than constant prices measured in a base year. Current PPP is the correct measure when comparing relative levels. See Feenstra, R et al., The Next Generation of the Penn World Table, American Economic Review, 105(10), 3150-3182, 2015. Source: Analysis of OECD, Level of GDP per capita and productivity dataset).

Whole economy Investment in the UK has been persistently low

Whole economy investment – or Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) – includes public and private sector investment, and encompasses investment in fixed assets such as buildings, machinery, Information and Communication Technology (ICT) and Research and Development (R&D). Public and private sector investment across all of these areas is important for raising productivity and reducing inequality.

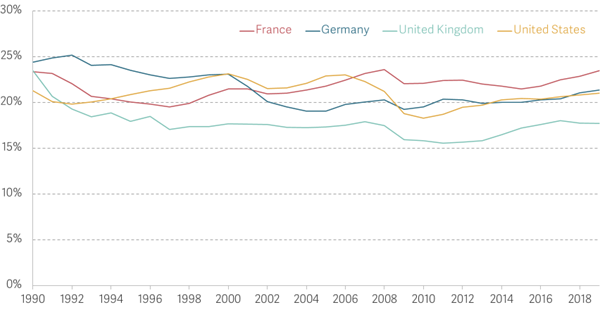

Figure 2 shows Gross Fixed Capital Formation as a share of GDP, in the UK, the US, France and Germany. On this measure, not only has the UK been investing less than its peers as a share of GDP since the early 1990s, but investment in the UK has been falling since 2017 while rising in these other countries.

Figure 2: Investment in the UK lags behind the US, France and Germany

Whole-economy investment as a share of GDP

(Notes: Gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) as a share of GDP. Ratio of series in current PPP USD.) Source: Analysis of OECD data.

UK performance in business investment is particularly poor

Both public and private sector investment matter for productivity. However, when looking ahead, the private sector is where the big challenge lies. After decades of underinvestment, the public sector has started to turn the corner, with public sector net investment at its highest sustained levels since the 1970s. On the other hand, private sector business investment remains poor; in the UK it was only 10% of GDP in 2019, far behind the average of 13% in France, Germany and the USA.

Investment in human capital is also needed

Alongside increasing investment in capital and ideas, the UK must increase its investment in human capital, where progress has slowed and outcomes are very unequal. This is true when we look at outcomes for young people leaving school; in the UK, the gap in numeracy skills between 16-20-year-olds who do not have a parent that attained an upper-secondary qualification (A Level equivalent) and those that did is the third largest in the OECD.

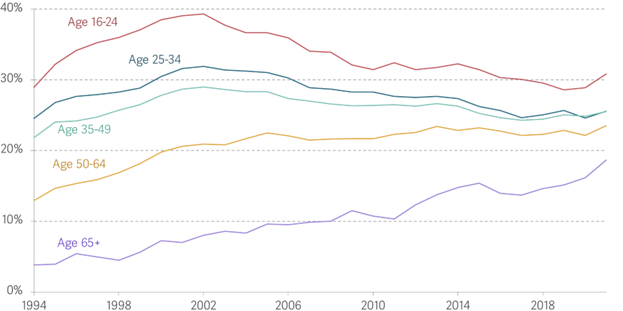

But we should not just focus on schools and colleges – there has also been a slowdown in workplace training, with the proportion of workers who report that they have received work-related training in the past three months falling from 29% in 2002 to 24% in 2020. Concerningly, this slowdown in workplace training has been most pronounced among younger workers. Between 2002 and 2020, those aged 16-24 saw their training rate fall by over a quarter (by 27%, falling from 39% to 29%), as shown in Figure 3. This fall in training amongst young workers has happened across occupations and is not the result of young workers becoming more represented in jobs that are less likely to provide training.

Figure 3: The fall in workplace training is concentrated among the youngest workers

Proportion of those in employment receiving work-related training in the past three months, by age group: UK

Source: Analysis of ONS, Labour Force Survey

Recommendation 1

Policy makers need to be serious about boosting productivity growth in the 2020s to improve living standards for low-and-middle income households across the UK.

Recommendation 2

There needs to be an increase in capital investment, particularly in the private sector, to close the gap between the UK and countries such as France, Germany and the US.

Recommendation 3

There needs to be greater investment in human capital to both improve outcomes for workers and boost productivity in the UK

By Louise Murphy, Economist, Resolution Foundation

This article is part of Campaign for Learning’s series: ‘Driving-up employer investment in training – pressing the right buttons’.

Part One: Employer investment in context

- Louise Murphy, Economist, Resolution Foundation: Investment in the round

- Dr Vicki Belt, Deputy Director, Enterprise Research Centre, Warwick Business School: UK enterprises and investment in capital and training

- Becci Newton, Director, Public Policy Research, Institute of Employment Studies: Employer investment in training in England

Part Two: Drivers of employer investment in training

- Neil Carberry, Chief Executive, Recruitment and Employment Confederation: Derived demand, British management and employer investment in training

- Ewart Keep, Professor Emeritus, Education Department, University of Oxford: Strategies to drive-up employer investment in training

- Sam Alvis, Head of Economy, Green Alliance: Transitioning to net zero, green skills and employer investment in training

- Dan Lucy, Director of HR, Institute of Employment Studies: Job quality, job design and driving-up employer investment in training

- Natasha Waller, Policy Manager, LEP Network: Local inward investment, business support and employer demand for training

- Jovan Luzajic, Acting Assistant Director of Policy, Universities UK: Universities, R&D, business innovation and meeting employer skills needs

- David Hughes, Chief Executive, Association of Colleges: FE colleges, business innovation and meeting employer skills needs

Part Three: Increasing employer investment in training

- Paul Bivand, Labour Market Consultant: Why should employers invest in training in a flexible labour market?

- Aidan Relf, Skills Consultant: Why should employers invest in training with large net worker migration into the UK?

- Stephen Evans, Chief Executive, Learning and Work Institute: Raising employer investment in training

- Robert West, Head of Education and Skills, CBI: Increasing employer investment in training

- Lizzie Crowley, Skills Policy Adviser, CIPD: Encouraging employer demand for training

- Anthony Painter, Director and Daisy Hooper, Head of Policy and Innovation Chartered Management Institute: Increasing employer demand for management training

Part Four: Raising employer demand for publicly funded post-16 education and skills

- Jane Hickie, Chief Executive, AELP: Increasing employer demand for post-16 apprenticeships in England

- Mandy Crawford-Lee, Chief Executive, UVAC: Increasing employer demand for level 4-5 technical education in England

- Ian Pryce, Principal, The Bedford College Group: Increasing employer demand for higher technical education in England

Part Five: Raising employer demand for work placements

- John Widdowson, Board Member, NCG: Increasing employer demand for work placements for level 3-5 vocational courses in England

- Stephen Isherwood, Joint Chief Executive, Institute of Student Employers: Increasing employer demand for undergraduate work placements in England

Responses