Effective learning for the next generation

The annual EdTech Summit is always a thought-provoking event. This year’s edition, which takes place at the NEC in Birmingham on 17 November, promises to be no exception.

The session the ETF is hosting – The Effective Learner: How the Next Generation Will Learn – aims to cut straight to the heart of the very important debate about how learning will happen in the future. That’s a fundamental consideration for all providers, who must seek to understand the expectations their learners have of how they will learn, how those expectations change as learners progress from school through their lifelong learning journey, and the role EdTech plays in influencing what they expect.

Understanding learners’ expectations isn’t necessarily straightforward, of course. There is sometimes a difference between what students might say they want of their learning and what they actually need to be effective learners, and it is for us to understand that and strike a balance that serves their needs.

The concept of the independent learner

I come at this debate from a start point of thinking about the concept of the independent learner, which has become increasingly important within education. Although it is not new, it is not always understood or defined consistently. As Stephanie Mckendry and Vic Boyd pointed out a decade ago, when it is discussed expressions such as ‘self-regulated,’ ‘independent,’ and ‘lifelong learner’ are all used interchangeably.

We are fortunate in having many learned opinions around which we can coalesce our understanding of what independent learners are. The main issue with the concept is that it implies isolation; in 2010, Maggie Leese even identified a link between the concept of the independent learner and student anxiety and progression issues. As Knud Illeris points out, learning is not only a cognitive activity, it is also an emotional and social one. This observation is nothing new; over a century ago John Dewey was describing education as “a social process”, and nearly two-and-a-half millennia ago Aristotle observed that “Man is by nature a social animal”.

If we take the Oxford Dictionary’s definition of learning – “the process of gaining knowledge and skills through studying” – we see it is an activity of construction; the construction of knowledge. Our ability to learn, however, depends on several factors. Some are intrinsic, such as our motivation and confidence, and others are extrinsic, such as our social and cultural backgrounds. This ability is also influenced by a range of other factors and motivations, such as whether we are employed or unemployed and what kind of resources and support we have access to. One perspective, which has been explored by Daniel Susskind, is that some people see learning to a capital investment, an activity we might engage with at the beginning of our lives but forget about once they get a job.

What has changed?

The world has changed though. Digital technologies are now part of our lives and they are not going away. It is time for us to make the most of them to enhance learning and teaching.

We have entered the fourth industrial revolution. The impact of this digital revolution is already evident, and change is now established as a constant state. The journey ahead is one that will be characterised by constant upskilling and reskilling. Learning provides the answer to this state of constant change; its reward is our continued capacity for growth, a fact noted by Dewey over a century ago.

But does the way we teach reflect this? Before the Covid pandemic there was sometimes a tendency to teach the way we were taught, and the way we have taught in the past, assuming learners would be engaged in the same way we once were.

The pandemic prompted a profound change in teaching of course, with a switch to remote and blended delivery as a matter of necessity. But we need to ask ourselves whether this redefining of pedagogic approaches means we are delivering our teaching effectively; are our techniques preparing our learners to live, work and study in a digital world, or are they just getting enough knowledge and skills to stick so that learners can pass an exam?

A new approach for a new era?

The responsibility of all of us working in education is to equip learners with the knowledge and skills they need to secure a place at a university, start an apprenticeship or find a job, but the purpose of education is, of course, far broader. As Alison Gopnik pointed out in 2017, “Educators, pedagogues and practitioners need to be gardeners rather than carpenters” – our role is not only to make knowledge and skills stick, but most importantly, to nurture the development of independent thinkers, whatever their age may be.

Although we shouldn’t forget that some members of society are subject to the limitations of digital poverty, facing challenges accessing devices or data, the internet facilitates what Chandra Orrill describes as a “shift from thinking about teaching as providing information to thinking of learning and creating learning environments.” This in turn creates a relationship shift between teachers and learners. Although the teacher remains the subject expert, they are no longer the sole information holder, and their roles as guide, coach and facilitator come to the fore. That, as Orrill points out, is an “evolution toward inquiry-based learning and toward the development of a learner-centred environment.”

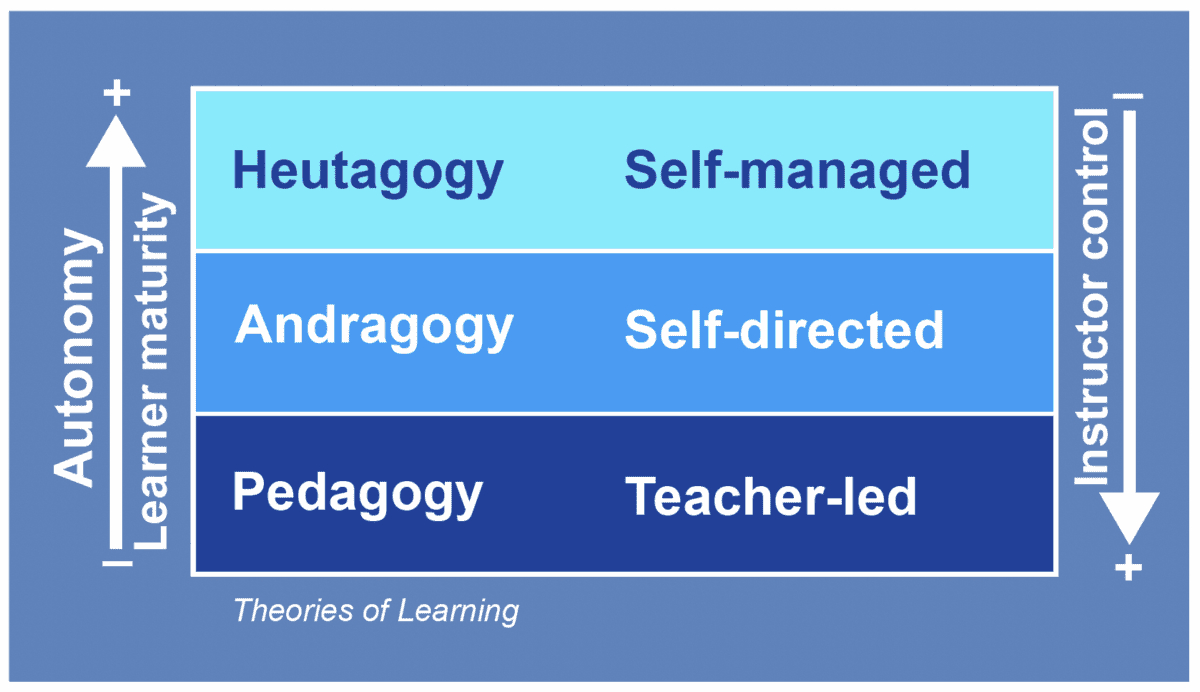

That’s a different type of learning. While pedagogy is teacher-led, andragogy is self-directed learning, with students in such environments using the teacher as a mentor or guide. The key difference Knowles identified is that children’s learning (pedagogy) is motivated by the acquisition of knowledge and training (they are receivers), whereas adults’ learning (andragogy) is motivated by self-actualisation, through the organisations where they live and work, in which they aim to find solutions to the teacher’s tasks independently. Heutagogy takes a different approach. It is the management of learning for self-managed learners.

The way forward

And it is that thinking that underpins the session we will be leading at the EdTech Summit. That it will address the effective learner, rather the independent one, is of course a conscious decision. As Rick Wormeli has explained, we need to be thinking about the skills associated with effective learning, and how passive consumers of learning become active ones.

I’m pleased to say that the session will welcome an array of expertise in the form of guest speakers Amy Hollier (Director of Blended & Online Learning, Heart of Worcestershire College), Deb Millar (Executive Director of Digital Transformation, Hull College), Hannah Mathias (Head of Digital Education Services, University of West England), Laura Dickinson (E-learning Lead Practitioner, North Tyneside Learning Trust), and Nishy Lall (Head of Young People, Sky). We look forward to hearing their insights into how we can help to ensure the new generation of learners learns effectively.

Responses