Know What a Win Looks Like – Meaningful Apprenticeship Quality

More than 3m starts, 372 days in learning & 20% off the job

Our apprenticeship reforms will support an increase in the quality & quantity of apprenticeships …

so said the ‘Government’ in May 2017 when they launched the ‘new’: Apprenticeship Funding system

We will have to wait and see if the increase in quantity will come…..but what does an increase in quality actually mean and would we recognise it if we saw it.

If we have 3million people all doing 20% ‘off the job’ training on apprenticeships that last a min of 372 days, will this mean that we have cracked it?

Clearly not; a long and weighty apprenticeship could still be of poor quality. On its own size measures only signify compliance – not Quality or even value for money.

The minimum duration rule came in as a response to the decline in average duration that was prompted by the last government apprenticeship target (dangerous things targets…).

‘20%’ is designed to ensure that the new 3million target doesn’t result in similar issues.

But the ‘rule’ has caused much debate and it is clearly both challenging and helpful in equal measure:

- Helpful in ensuring that an apprenticeship is a ‘weighty’, meaningful, course (as well as a job) and in articulating how ‘doing an Apprenticeship’ is more than just ‘doing a job’ as it requires dedicated time set aside for learning

- But it is unhelpful if it means that providers, employers and especially auditors start counting hours, and we then start doing things just to ‘make up the 20%’ – if this happens we will have all completely missed the point and taken a step backwards

As the 20% rule isn’t going away anytime soon (famous last words!) I think we all need to move on and start to exploring and debating what are the more meaningful measures of quality.

The key quality questions

The recent IFA Quality statement and strategy are really helpful way to start this debate and should prompt us as ‘employers and providers’ identify the fundamental questions:

- What impact should good quality apprenticeships make

- How do you deliver good quality

- What is good quality (beyond 20% & 372 days)

1) What is good quality in terms of apprenticeship?

The opening text of the Quality Statement defines an apprenticeship as:

….a job with training to recognised standards. It should involve…. a substantial programme of on and off-the-job training…

This key sentence provides a helpful continuation of policy and definition, stretching at least back to 2013 and Unwin and Fuller (surely our leading Apprenticeship academics).

They proposed that a high-quality apprenticeship is one that is ‘expansive’:

“Expansive Apprenticeships stretch apprentices …they are given the opportunity to acquire skills and knowledge that will help them progress in their occupation and their developing expertise is seen by their employers as central to success. This requires structured and substantial training, and rigorous assessment. Importantly.., apprentices have a dual identity as workers and learners.”

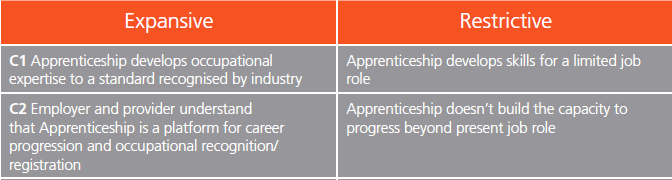

Unwin and Fuller also really helpfully produced a tool for assessing apprenticeship programmes against this definition. Their work helps us move beyond a linear assessment of apprenticeships as being either ‘good’ or ‘bad’ – compliant or not. By introducing the concepts of ‘Restrictive’ and ‘Expansive’ they gave us a quality gauge against which to assess an apprenticeships’ real value and thus its quality.

- Restrictive Apprenticeships – may meet the rules but don’t have a meaningful impact

- Expansive Apprenticeships – create real and profound change and benefits

Their guide contained 11 ‘challenges’ for identifying a good quality apprenticeship. The first two of these still stand out as being particularly valid and important in differentiating between compliance and quality and importantly they also fit well with the recent IFA definition.

They are also a helpful starting point for anyone charged with ensuring their new levy-fuelled programme is of ‘high quality’:

Do the new ‘Standards’ help ensure new quality?

The IFA statement focuses clearly on new standards and the government clearly still hopes that the majority of apprentices will be on new standards by 2020 (we shall see).

The new standards have within them three core elements:

- Knowledge: what must you know to become classed as a professional

- Skills: what must an apprentice be able to prove they can do consistently well

- Behaviour: how should a professional in that occupation act and interact

The first of these elements ‘knowledge’ should be the biggest differentiator between Frameworks and Standards (and is also the biggest cost and stretch for providers). It necessitates a well prepared and meaningful curriculum, a core theoretical base of information that underpins the apprenticeship academically. This is not ‘on the job’, but classroom (virtual or actual) learning.

The knowledge element of each Standard also provides an opportunity for employer groups to renew definitions of professional competence and opens the door to a common curriculum amongst all Apprentices undertaking the same Standard – irrespective of the differences in their employment.

So for example every Assistant Accountant apprentice will need to acquire the same level of knowledge regarding ‘Book keeping’ and ‘Financial Regulation and Compliance’, regardless of their own age, education and experience, their exact job role and their employer’s size or sector. This gives common Knowledge base gives the apprentice portability and a platform for recognition and progression – and helps to distinguish the apprenticeship from ‘doing the job’ training.

It is the quality and consistently of this knowledge-teaching that can move apprenticeships forward and this should surely be the main focus for internal quality teams and for Oftsed.

2) How do you deliver good quality?

According to our new FE Apprenticeship teaching standard (developed by providers with expert support from the ETF)

“Learning and Skills Teachers (LSTs) are responsible for planning and delivering learning that is current, relevant, challenging, and that inspires learners to engage and achieve their full potential”

This fits well with the Unwin & Fuller and IFA definitions. The LST standard also requires that they should have ‘relevant industry experience’ and I think it is this industry experience which distinguishes our tutors from School teachers for example.

There is also a new standard for Assessors and Coaches

“ACs coach and assess vocational learners, usually on a one-to one basis, in a range of learning environments. These skills are also integral to assessing learners’ competence in-relation to work-related/industry standards and life skills.”

These two distinct roles highlight the two key pillars of apprenticeship training Knowledge acquisition – and Practical application (hence the term dual-learning for apprenticeships).

It is the complimentary nature of these two aspects of an apprenticeship which combine to make it such a powerful form of learning – ie if academia is all theory and on the job training is all assessment – a high quality apprenticeship provides both elements.

So to deliver good quality you need to teach the theory and assess the competence.

3) Measuring the impact of good quality

Of course the person who is best placed to appreciate the impact of a good quality apprenticeship is the person who has actually undertaken it. With an advancement in their career prospects ultimately being the most important evidence of its impact.

Beyond this how can we measure the impact on employers and the wider economy?

Those countries with long term, large-scale, successful Apprenticeship programmes (i.e. Germany and Switzerland) have focused on two things, as the core measures of programme success:

- The Return On Investment (ROI) achieved by employers with apprentices (Warwick did a great job of this in the UK here) &

- Total demand for apprenticeships amongst school leavers : as this shows the relative value assigned to apprenticeships by society (compared to HE)

Those countries do also have guides for min learning hours and min practise hours (on the job practise hours) but these aren’t seen as quality indicators, our outcomes.

These two measures (A&B) don’t work easily for us, as we have an all-age, all-level programme where the majority of apprentices are already employees, making it almost impossible to isolate programme level cost-benefits and demand levels.

However they are surely key things for any employer to measure when assessing their own programme:

- Has the money we have spent on the apprenticeships been worthwhile – what is the ROI for each £ spent &

- Are our apprenticeships attractive to potential and existing employees (demand)

So how can we measure the impact of good quality apprenticeships at a macro programme level?

The most commonly used measures of ‘quality’ here are Oftsed grades and Success rates.

Oftsed grades are a good indicator of overall organisational effectiveness and its attention to Oftsed guidelines – but there could easily be a large difference between an organisation’s Oftsed grade and the quality of their Apprenticeship programme – which may be only a small component of their overall offer.

Success rates show how many people complete an apprenticeship. However not many Apprentices ever failed their apprenticeship – they just ‘dropped off’, moved on, or gave up. The introduction of End Point Assessment might change this, and allow us to measure retention / completion rates (of the training) separately from EPA pass rates.

This is important as EPAs might also give Apprentices another reason for not completing (as not doing so saves them work and saves their employer money).

The current success rates measure the perseverance of all parties involved but they could be a real issue going forward if EPAs do provide a reason not to complete, so the IFA introducing an ‘up to EPA’ retention measure is to be welcomed I think.

Other programme level assessment measures such average durations and participation numbers are useful, but they are as much a reflection ‘funding’ rules and availability as they are indicators of actual experience and value.

So as well as the macro indicators in the IFA statement, it might be an idea to also try and measure some of the following in order to more fully understand the impact that good quality apprenticeships should make:

- The background of apprentices – who aspires to an apprenticeship

- Skills shortages – do apprenticeships lead to a reduction of skills shortages

- Longer term employment impact – do apprenticeships provide sustainable employment platforms

- Productivity impact – do apprentice employers experience productivity benefits (ROI)

- Consumer voice – how satisfied are apprentice employers and apprentices themselves

- Annual External Quality Assurance – do EPAs have an impact

As we seem to have bet the FE ‘house’ on Apprenticeships, we need to make sure we all know what a win looks like.

Richard Marsh, Apprenticeship Partnership Director, Kaplan Financial

Responses