Young people and jobs: What can we do to help in 2021 and beyond?

Looking to the future

The Covid-19 pandemic is not just the worst global healthcare emergency of the last century, it also represents an employment crisis, particularly for young people. In any recession, young people can expect to be disproportionately hit.

As demand for goods and services falters, the employers respond by halting recruitment and then when things ease, young people find themselves facing tougher competition from older workers. It is a contest that new entrants to the jobs market begin on the back foot: overwhelmingly, they have less experience of work, fewer useful contacts to help get a job, and less know-how about how to find employment.

Concerns over the well-being of young people facing employment is great because evidence shows that they can expect to be scarred by the experience. That is to say, the young unemployed can expect to do worse economically and psychologically over the long-term.

Many worry about the generation that is now leaving education. Not only is it facing a deeply hostile labour market, it is also the most highly educated and most ambitious generation in history to attempt the transition from education to employment. It is a cruel disjuncture.

New work by the OECD is designed to help schools and colleges gain greater confidence that their student are on track to do as well as possible in difficult labour markets. At the end of this article, there is opportunity to find out more and get involved.

Narrow, confused and distorted

Recent work by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) raises still deeper concerns. In January 2020, we published Dream Jobs?, an analysis of the career aspirations of the 650,000 15 year-olds who completed the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA).

The analysis found that in many countries, teenage job ambitions can be characterised as narrow, confused and distorted by social background. We found that many young people, particularly from more disadvantaged backgrounds, underestimate the education they need to achieve their career ambition.

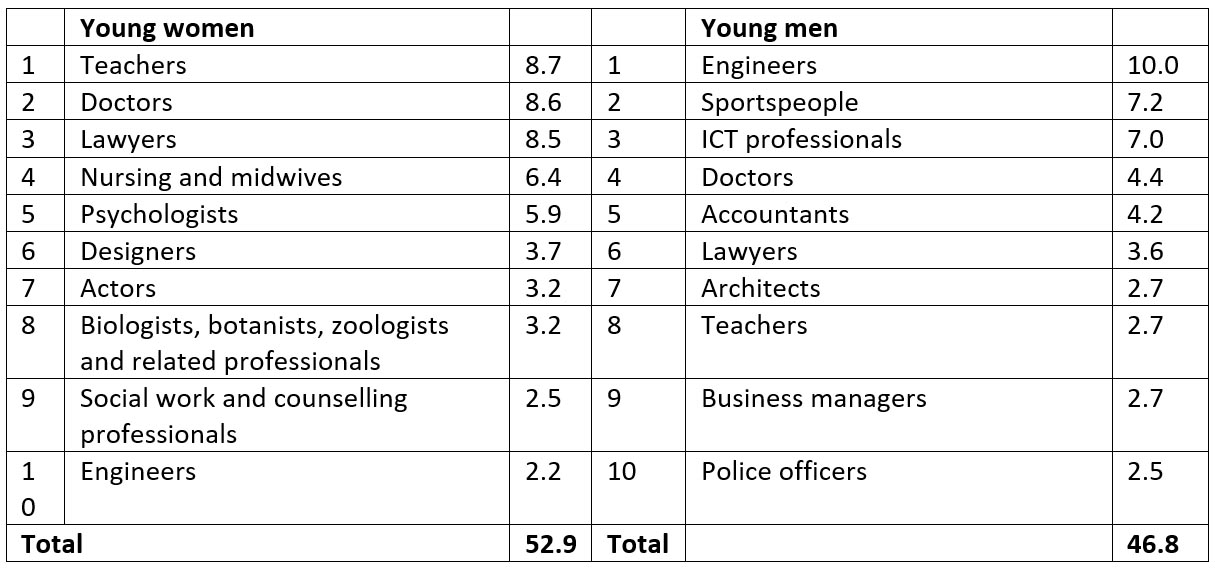

We also discovered very high levels of concentration in teenage aspiration. In many countries, such as the UK, around half of students who have a job ambition aim for one of just ten popular (and very traditional) jobs.

Student occupational expectations, UK. PISA 2018

Interest in the skilled trades

This is a concern because in the UK, as in many other countries, some young people go into full-time work or training at 16 and many make important decisions about how they will specialise in their studies. It also tells us something important about the effectiveness of employers in signalling job opportunities to young people. Perhaps most striking, is the poor representation of jobs in the skilled trades in student choices.

Such jobs which are typically entered through programmes of Vocational Education and Training (VET) can become especially important during a recession. Where employers have a clear self-interest when they participate in VET programmes, they provide confidence that there will be a skilled job at the end of the training programme.

When self-interest in not distorted by excessive artificial incentives and where vocational systems enable responsiveness to changing patterns of employer demand, effective VET systems will enable transitions into employment even in difficult economic circumstances. We saw this in Germany and Switzerland during the Great Financial Crisis. Whereas across Europe (including in the UK), youth unemployment shot up after 2008, in German-speaking countries with strong VET systems this wasn’t the case. The success of Germany and Switzerland has been influential around the world and it is hoped that in this recession, strengthened VET systems in the UK and elsewhere will help young people withstand the worst consequences of the downturn.

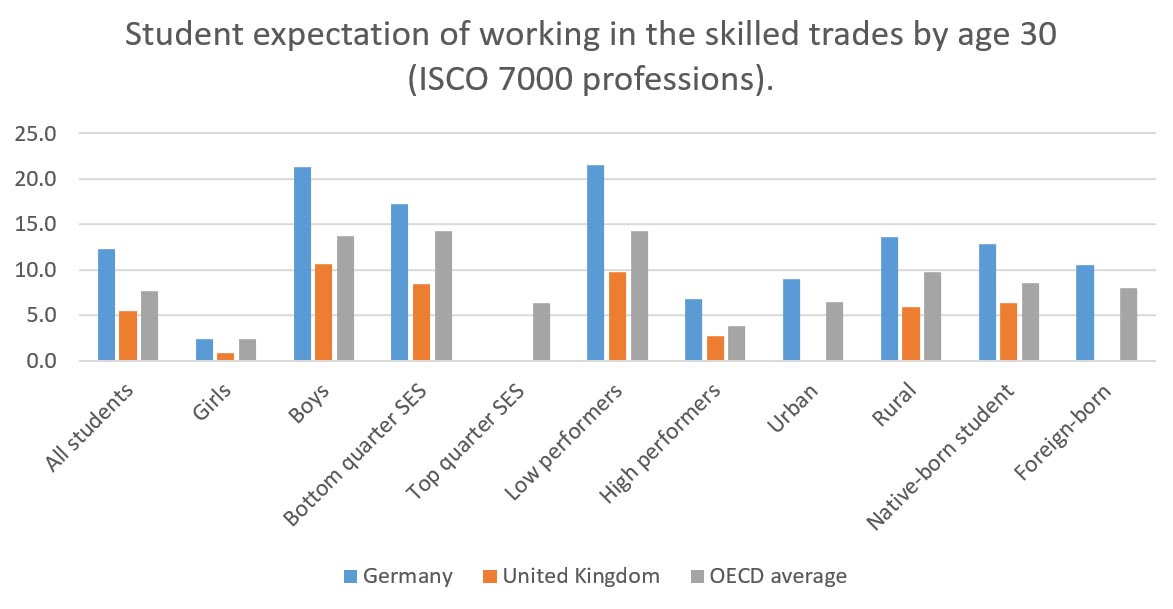

Chastening evidence from PISA 2018 however, shows that young people are still hesitant to pursue VET programmes into skilled employment. The representative survey allows comparison of how many and what types of young people expect to work in the skilled trades at age 30.

These are the International Standard of Classification of Occupations (ISCO) jobs in the 7000 series, like:

- house builders,

- bricklayers,

- carpenters,

- roofers,

- glaziers,

- plumbers,

- refrigeration mechanics,

- painters,

- welders,

- motor vehicle mechanics,

- aircraft engineer mechanics,

- jewellery makers,

- dress makers,

- instrument makers,

- printers,

- electrical workers,

- butchers,

- bakers,

- tailors, and

- cabinet-makers.

As the table below shows, in Germany twice as many young people expect to work in such jobs as in the UK. In the UK, overwhelmingly it is low-performing, native-born young men of lower socio-economic status living in more rural areas who anticipate pursuing such VET programmes.

While students in other OECD countries exhibit similar patterns, they are particularly accentuated in the UK. The data suggest that VET provision linked to the skilled trades remains unattractive to many young Britons.

Indicators of employment success in the pandemic: get involved

Analysis by the OECD and others shows that what young people think about their futures in work and how they explore and experience potential future workplaces makes a difference to their later outcomes.

New research has reviewed analyses of national longitudinal databases from around the world and found consistent patterns. Where students demonstrate engagement in their likely working futures they can expect to do better would be anticipated given their qualifications and backgrounds (see: Career Ready? How schools can better prepare young people for working life in the era of Covid-19).

Over the next year, we will be undertaking further research across a wider range of databases. By the end of 2021, such indicators will serve as the basis for new tools for practice and policy. The project team will be inviting schools and colleges from around the world to get involved.

Anthony Mann, Senior Policy Analyst, OECD

If you would be interested to being kept updated, please email Anthony.Mann@oecd.org to join OECD’s informal project stakeholder group

Responses