The UK’s Shrinking Workforce

The UK is the only OECD Member country, except for Switzerland, to have seen a sustained rise in economic inactivity since the start of the pandemic. The rise in people who are not working and not looking for work has led to significant labour shortages, with impacts for the businesses struggling to recruit and a low growth economy. The Chancellor highlighted this weakness in his speech on economic growth last week. So what’s happened and how might the Government support people to move back into work?

It is important to say that economic inactivity isn’t particularly high in the UK, compared to other developed countries, and many countries are facing widespread labour shortages. The difference is that, while participation rates have bounced back to pre-pandemic levels in many other countries, the UK workforce continues to shrink.

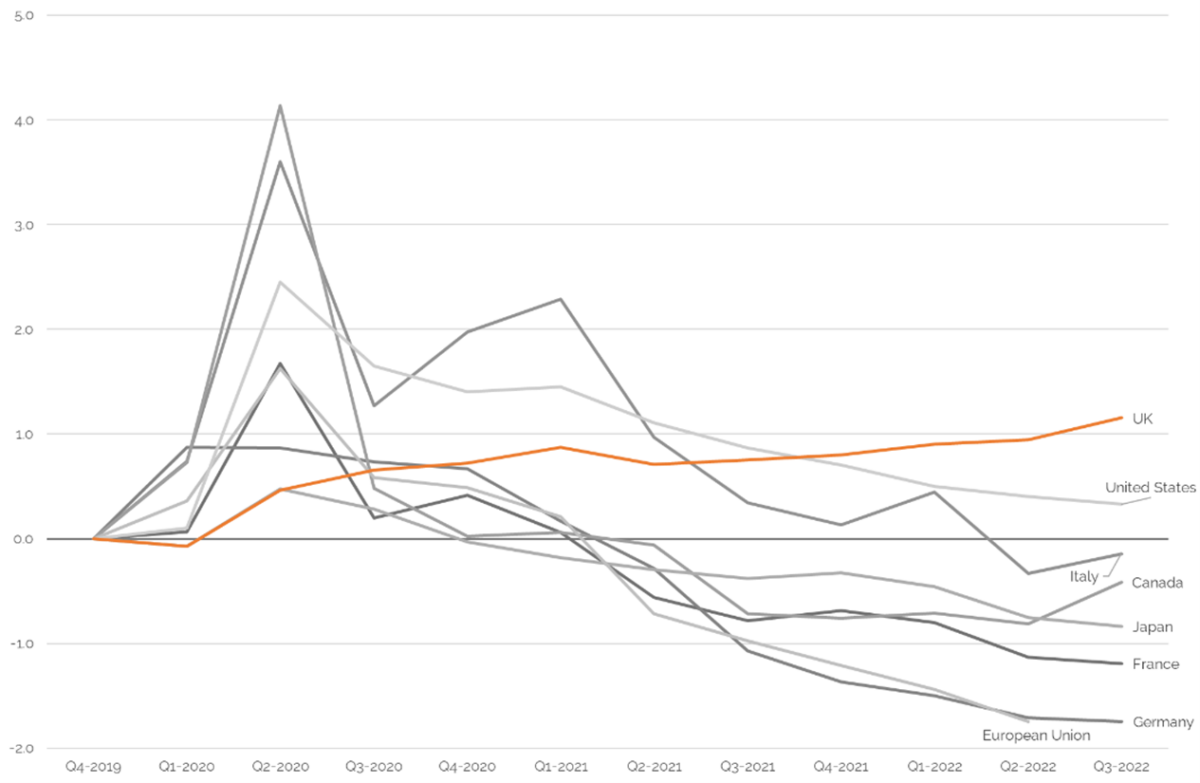

While many countries saw large peaks early in the pandemic, economic inactivity rates are now lower in most other OECD countries compared to pre-pandemic, and in nearly all compared to the highest peak during the pandemic. By contrast, the economic inactivity rate in the UK is at its highest point since the pandemic started. Overall, the number of people economically active in the UK is around one million lower than if pre-pandemic trends had continued.

Percentage point change in economic inactivity (cumulative) since Q4 2019 (G7 countries and EU)

Much of the rise in economic inactivity has been driven by older workers leaving the labour market. The latest figures show there has been a 9.5% increase in people aged 50-64 who are economically inactive, up to 3.5 million, and there are 635,000 fewer over 50s in the labour market since the pandemic started.

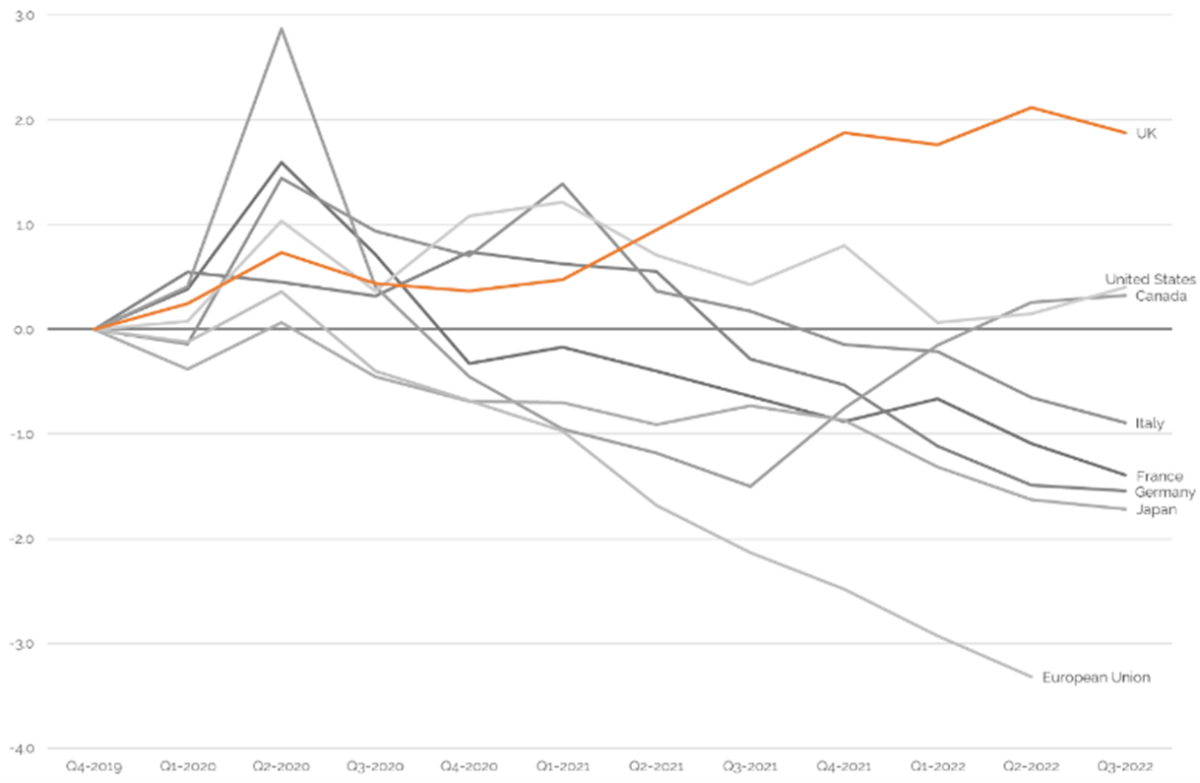

The rise in economic inactivity rates among older people is the opposite to what we’ve seen in other countries. The UK is one of just eight OECD Member countries where economic inactivity rates among 55-64 year olds remain higher compared to pre-pandemic levels, ranking fourth behind Chile, Colombia and Costa Rica and first among G7 countries.

Percentage point change in economic inactivity for 55-64 year olds (cumulative) since Q4 2019 (G7 countries and EU)

There’s been a lot of debate about why economic inactivity has continued to rise in the UK, particularly when it’s falling elsewhere. Much of the debate has focused on two broad schools of thought: one is that more people are deciding to retire early and the other is that more people are too sick to work.

IFS analysis, looking at flows of people in and out of the labour market, shows that the biggest driver in people in their 50s and 60s leaving the workforce is retirement. At the same time, more economically inactive people are reporting ill health as the main reason they are not working. People economically inactive due to ill health has risen by 15% since the start of the pandemic – compared to a 0.7% increase in 16-64 year olds inactive due to retirement. So while people may not report ill health as the main reason why they’ve left the labour market, it is a barrier to going back to work for many.

The reality is that people’s lives are complex and decisions around work are likely to be driven by multiple factors. Much of the analysis to date has focused on people’s main reason for being inactive, while there are likely to be several. Alongside people’s personal circumstances, their experience of work will weigh into their decisions too. Phoenix Insights have found that people in the UK were significantly more likely to have negative attitudes to work and that the views had changed more profoundly since the pandemic than those other countries.

So how can we support people back into work? And support more people to stay in work?

- Expand access to employment support. Regardless of the reason why people have left the labour market, 1.7 million people would like to work. Yet employment support is focused on those who are unemployed and claiming benefits, and only 1 in 10 out-of-work disabled people and older people get help to find work. The potential £2 billion underspend on Plan for Jobs could be used to widen eligibility for programmes such as Restart and the Work and Health Programme to include groups that are economically inactive. Reaching those beyond the narrow group that is in contact with Jobcentre Plus could be achieved by working with the organisations, such as Housing Associations, local authorities and community groups, that people are already in contact with.

- Integrate work and health. A growing number of people are not working due to ill health, with a sharp increase in mental health conditions. There is strong evidence on the effectiveness of Individual Placement and Support (IPS), involving intensive, individual support, rapid job search and in-work support to help those with mental health conditions find and retain work. Integration between employment support and health is a critical success factor. Finding ways to build on successful models, such as IPS, and more fully embed the underlying principles is critical if we’re to address barriers to work. We also need to help people stay in work. Access to Work has worked well in this respect, but the Government needs to ensure applications are processed swiftly and think about how to expand awareness, take-up and support.

- Better support for people in their 50s and 60s. For over 50s considering returning to work, finding a job that offers flexibility (in hours and location), pays well, and suits their skills and experience are top priorities. High quality, tailored employment support can help people find the ‘right jobs’ but it often falls short, particularly for older people. One way to improve support for people later in their working lives, whether they’re in or out of work, is through mid-life reviews. We piloted Mid Life Career Reviews, delivered by employers, careers advisors, trades unions and others, ten years ago. They were highly successful, with the evaluation finding that they supported people to return to work, better understand opportunities to change job, negotiate appropriate working conditions, find appropriate training and make realistic decisions about extending working life. They also improved people’s health and wellbeing, and were consequently taken up by pensions providers, Jobcentre Plus and others.We’d like to see this type of support being made more widely available and promoted to more employers.

- Work with employers. Employers have a key role to play, thinking about where and how they recruit, and how they design jobs that offer quality, flexible opportunities. Employers groups have established a range of different initiatives, such as the CBI’s Work Health Index, to spread best practice. The Government should look at how it can partner with these groups and local chambers of commerce to build on and broaden the reach of campaigns focused on recruitment and job design. We also need to look at how to engage employers more effectively in employment support programmes and increase the types of training for managers, including workplace mental health training, found to be effective in supporting job retention and reducing sickness leave.

- Work with local leaders. The most effective way to achieve the above is to work with local leaders and partnerships. We often talk about the UK labour market as if it’s one homogenous thing but there are a multitude of local, overlapping labour markets with different characteristics and challenges. For example, 1 in 7 people in parts of Merseyside are economically inactive due to LT sickness compared to 1 in 100 in parts of Surrey. Local leaders are best placed to understand what’s happening in the labour market, join up provision and work closely with employers. The Government could work with local areas to agree plans to engage and support people who are economically inactive, as part of the next round of devolution deals. It could also increase local employment support by bringing forward UK Shared Prosperity Fund employment and skills support, currently scheduled to begin in 2024-25.

Responses