The return of exams: the Sutton Trust view ahead of results day 2022

Results day is fast approaching for students who sat A levels and GCSEs this summer, who are the first students to sit formal exams since before the pandemic.

While the return of exams is a positive step back to normality post-crisis, the impact of the pandemic is far from over, and is likely to cast a long shadow on results day this year.

Exams and university admissions this year

2022’s GCSE pupils haven’t had a full ‘normal’ school year since they were in Year 8, while A level students last had the same when they were in Year 10. Since then, these students have faced two sets of school closures, and a sizeable amount of disruption even when schools were open, with high rates of both staff and student absences due to covid infections. And as exams were cancelled back in 2020, this summer’s year 13s missed out on sitting formal exams for their GCSEs, meaning the tests they sat this summer were their first ever formal examinations.

Mitigations were brought in to attempt to account for the pandemic’s disruption, with the main change being the pre-release of topics covered in papers in advance. Whilst the changes can take classroom-level learning loss into account, they do not account for individual-level learning loss, which students from the poorest backgrounds are more likely to have experienced.

There have also been early warning signs that there may be fewer places available at university this year, particularly at the most competitive institutions and courses, after universities took on additional students in the last two years following pandemic grade inflation.

Young people from poorer homes, who suffered the worst disruption during the pandemic, may be in a difficult position in what looks to be a very competitive market.

New research

Recent findings from the Sutton Trust have been able to dig deeper into the pandemic’s continued impact on students sitting exams this year, looking at the scale of ongoing disruption and the views of both students and teachers on the mitigations in place.

Our research looks at results from polling of 4,089 teachers (either teaching A levels, GCSEs or in their school’s senior leadership team) surveyed via TeacherTapp just after students headed off for study leave, as well as 434 students who have applied to university this year surveyed via Savanta, polled just after they had taken their exams this summer.

The continued impact of the pandemic

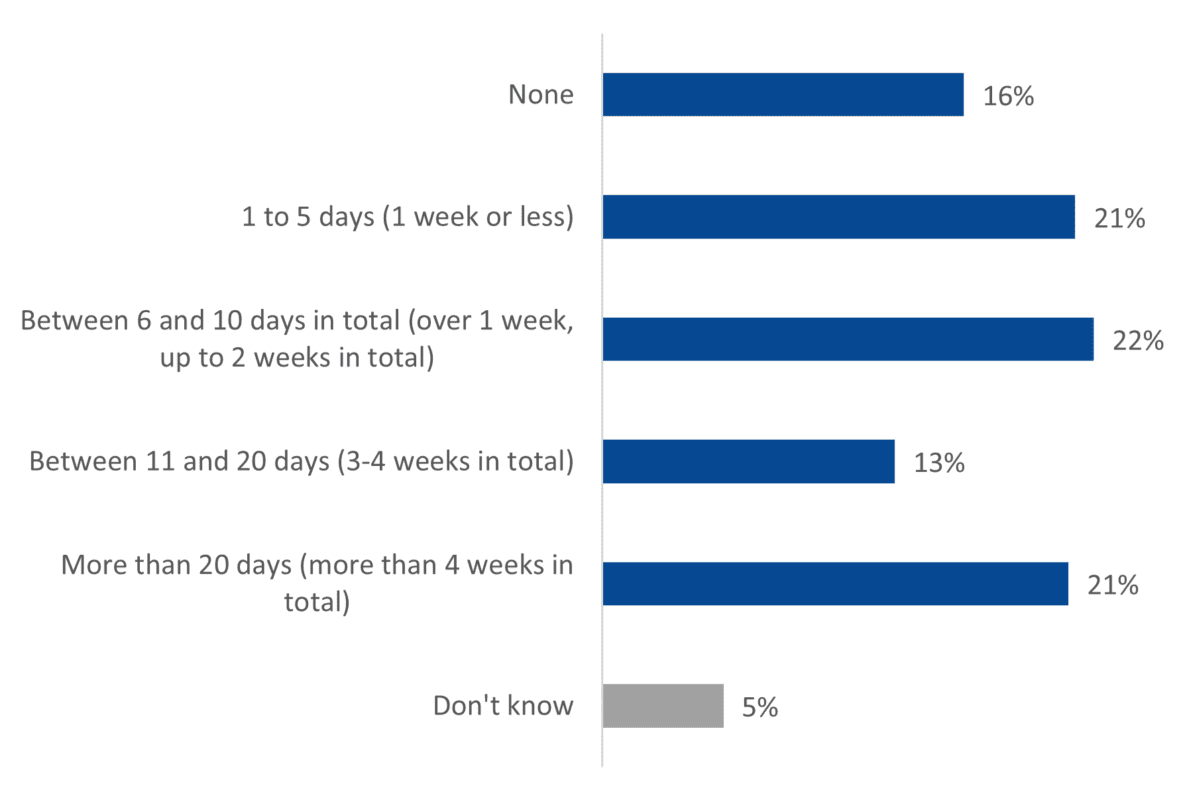

The report found that many year 13 students missed a considerable amount of learning time over the past academic year. Over a third (34%) of this year’s university applicants have missed 11 or more days of school or college over the last academic year due to covid related disruption, with 21% missing more than 20 days (shown in Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Days of school or college missed due to covid related disruption during the 2021-2022 academic year

Source: Savanta survey of university applicants for the Sutton Trust, 1st to 5th July

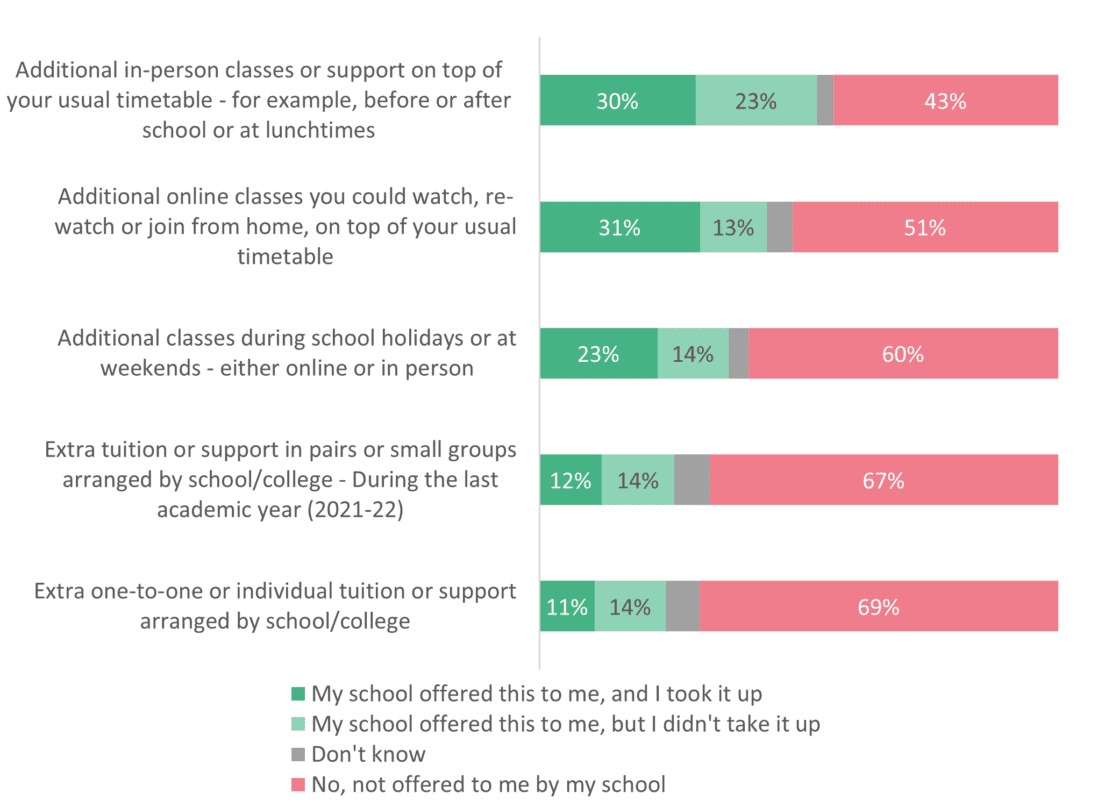

Looking at the catch-up provision offered to year 13s this year, 74% of state school applicants said they were offered at least one of the catch-up activities we listed (which included additional in-person support, online support and weekend classes outside of the usual school timetable), but a smaller proportion, 56%, had actually taken up at least one (as highlighted in Figure 2). 36% reported being offered some type of tutoring (either one to one or small group), and 19% reported they had taken part.

Figure 2: Catch up support offered to and taken up by applicants in state schools this year

Source: Savanta survey of university applicants for the Sutton Trust, 1st to 5th July

62% of this year’s applicants felt they had fallen behind their studies compared to where they would have been without the disruption of the pandemic, only slightly lower than last year, when 69% said the same. This figure was higher for students in state (64%) than in private schools (51%).

Teachers are worried too, with nearly three quarters (72%) believing the attainment gap between the richest and poorest students in their school will have widen when this year’s grades come in. Nearly half (45%) of the teachers involved with exams this year thought the exam mitigations in place (such as advance information on the topics featured in exams) did not go far enough to account for the pandemic’s disruption. This was 46% for those working in state schools, compared to 38% in independent schools.

The views of students were similar, with only 52% saying the arrangements for exams this year had fairly taken into account the impact of the pandemic on students’ learning and 39% saying that the arrangements had been unfair. And considering only those who said they received early information on topics ahead of their exams, working class applicants were 7 percentage points more likely to say that the early information was not useful, at 30% compared to 23% of applicants from a middle-class background.

Concerns from students

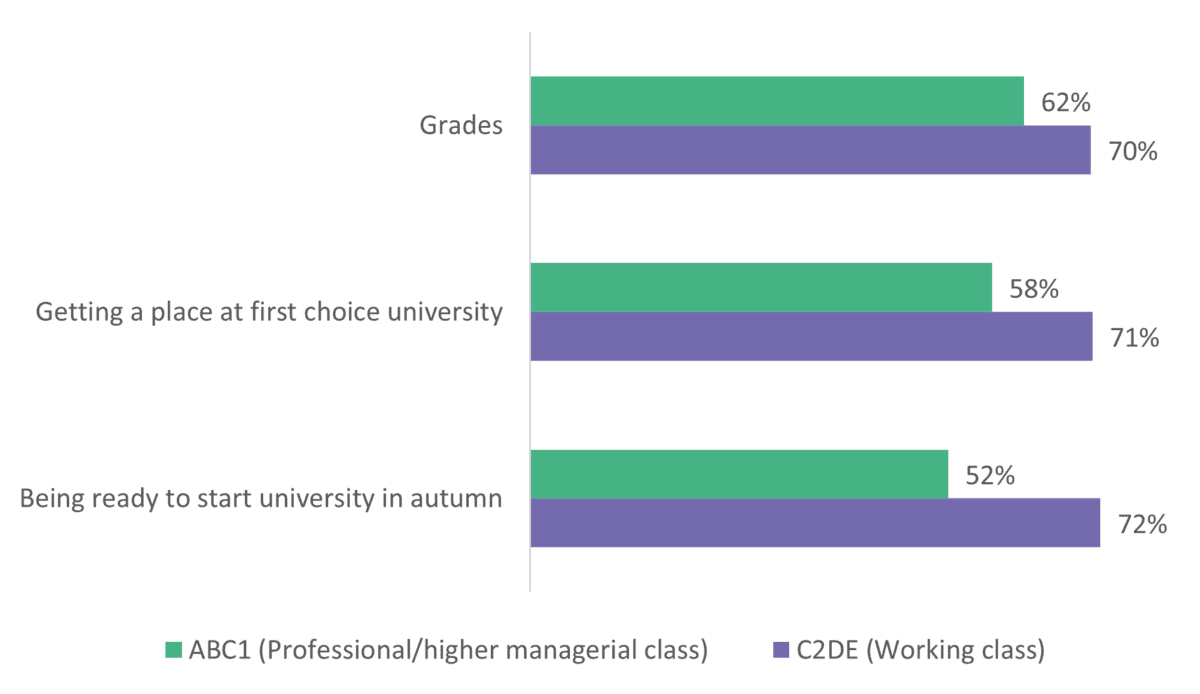

As results day approaches, it is understandably a stressful period for many students. Indeed, as seen in Figure 3 below, 64% of applicants said they were worried about their grades, a proportion which is 8 percentage points higher than the 58% of students who said the same last year. Students from working class backgrounds were 8 percentage points more likely to be concerned about their grades, at 70%, compared to 62% of those from middle class backgrounds. Working class students were also almost twice as likely to say they were very worried, at 41%, compared to 23% of those from middle class backgrounds.

Figure 3: Whether applicants were concerned over particular issues, by socio-economic group

Source: Savanta survey of university applicants for the Sutton Trust, 1st to 5th July

60% of students polled are also worried about getting a place at their first-choice university (13 percentage points higher than the 47% who said the same last year). 71% of working-class applicants expressed concern about getting a place, 13 percentage points more than those from middle class backgrounds (58%). Working class students were also almost twice as likely to say they were very worried, at 41%, compared to 23% of those from middle class backgrounds. And perhaps unsurprisingly, given the reported increase in competition this year, students who applied to a Russell Group university as their first choice were more likely to be concerned about getting a place, at 67%, compared to 56% of those applying to a Pre-1992 institution and 50% to a Post-1992 institution.

Furthermore, just over half (56%) were worried about being ready to start university in the autumn, (compared to 53% last year) with 19% saying they were ‘very worried’. A large proportion of those from a working class background said they were concerned, at 72%, compared to a smaller (but still sizable) 52% of middle class applicants. A third (33%) of applicants from a working class background were ‘very worried’ about starting university – just over double the figure that said the same from middle class backgrounds (15% reported this). Taking these findings into account, it seems likely we could see another stressful results day.

Moving forward

Whilst a return to relative normality has allowed students to sit exams again this year, the effects of the pandemic on their education have remained, with mitigations in place this year unable to fully reflect individual-level learning loss.

Universities, employers, colleges and other training providers making decisions on students’ next steps should take this context into account when making final decisions on the basis of grades from this year. Particular care should be taken when making decisions on students from disadvantaged backgrounds, who on average have experienced the most disruption throughout the pandemic.

After results day passes, and thousands of students arrive on university campuses, institutions should also look to provide additional wellbeing support for the incoming cohort. Many students are worried about starting university this year, and they are likely to need additional support for their wellbeing and mental health. Key gaps in learning should also be identified at an early stage, ideally in the first term, to ensure support can also be given to students who have missed out on learning in key areas necessary to succeed in their course.

The pandemic’s impact is still ongoing, and the impact will be felt by students taking exams next year too. Considerable measures have been announced for catch-up so far, including a recovery premium for school-aged children of £1 billion running until 2024, but the scale of these measures has not gone far enough – with the government’s “catch-up Tsar” resigning after saying the government’s plans were not of the scale needed. A 16 to 19 tuition fund was also announced, but eligibility for this has been criticised for being too narrow.

To support students who have missed a considerable amount of learning, the government should fund additional catch-up support for school and college students. A renewed catch-up plan, with a scale of funding at a level to meet the need caused by the crisis should be put in place by government for future year groups, including those in 16-19 education. This should include extending the pupil premium to students in post-16 education.

Whatever happens on results day, it will mark a key stage in many young people’s lives as they move on to pastures new. We must ensure that no young person is locked out of their next steps because of the unequal impacts of the pandemic, and ensure all have every chance to fulfil their potential.

Responses