Of Sugar And Spice And All Things Pay: The Gender Gap Starts At School

The gender pay gap has been in the news a lot recently, mainly driven by the new Gender Pay Gap (GPG) regulations introduced by the Government. These rules have encouraged around 10,000 of the largest employers in the UK to self-disclose their pay gap, which, by publishing this information, shames those with wide gaps into doing something about it. Theresa May has described the gender pay gap as a ‘burning injustice’.

The record holder is Boux Avenue with a ‘gap’ of 75.7%. So, now we know, what are they going to do about it?

The mass hysteria of the media jumping on the bandwagon, with their ‘mind the gap’ headlines, and sex discrimination commentaries, has been both a good and bad thing. There is a lot of awareness about the issue and information out there…. but also, there’s a lot of misinformation being written about the subject and, consequently, a lot of misconceptions about what the gender pay gap is not.

In this article we first want to look at the facts about what the pay gap is and is not; the research that explores the reasons for it; some of the initiatives used to address it, and then; consider how we at Kloodle can offer a solution from our end. Because we believe the roots of the gender pay gap start at school, we think the key to the solution starts there as well.

So, what is the pay gap then?

The ‘pay gap’ is the term which applies to the percentage difference in average hourly earnings between men and women. It is a measure of how much more men earn than women, in general.

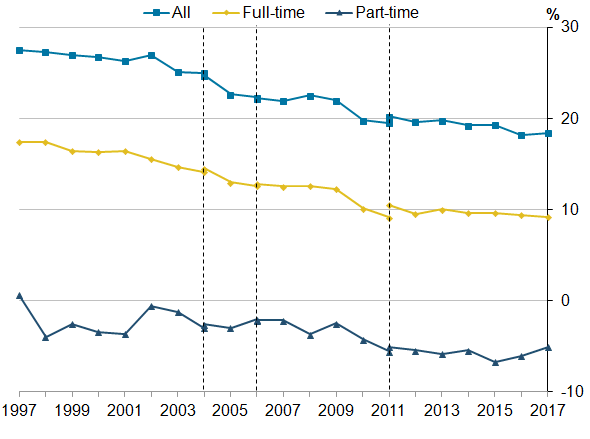

According to the Office for National Statistics, nationally across all industries, the median pay gap in the UK now is over 18%. The graph below shows that the pay gap has been falling over the past twenty years and Deloitte estimate that based on current trends the gap should be eliminated by 2069. For those who think we should get rid of it, this is a long time. But will it close? Is eliminating the gender pay gap the right thing to do?

What the gender pay gap isn’t .… is women getting paid less than men to do exactly the same job. That’s not allowed. The Equal Pay Act in 1970, which is supported by the Equality Act 2010, outlaws pay differentials based on gender.

Hence, the BBC being in the dock recently when it was exposed that some of their top female presenters were getting paid a lot less than their male counter-parts. What they said in their defence is what other organisations tend to say about their gender pay gap: you’re not comparing like with like.

So, the review that PwC carried out for the BBC found no evidence of actual pay discrimination. What it did find, though, when they looked at the pay structure, was that their gender pay gap was due to a “lack of clarity and openness” about how salary decisions were made.

This was then highlighted very publicly when the difference in what John Humphreys gets paid was compared to what Sarah Montague gets. Poor old Auntie struggled to explain this away.

What the gender pay gap is…..is women in society generally earning less than men. The reasons for this are because they:

- work in less well-paid employment, for example, in the health and social care sector

- work part-time, or

- fill the less senior positions that make up the lower pay grades in each sector.

A classic example to show where this happens is the airline industry, which has a relatively wide pay gap because pilots who are mainly male (95% of them) are paid more than the cabin crews who are mainly women. Simples. But, so what?

Well, why do women end up in these roles, why don’t more women become pilots? Not so simples. You can’t just call up your air hostess, however fantastic she may be, and ask her if she fancies flying the plane for a change!

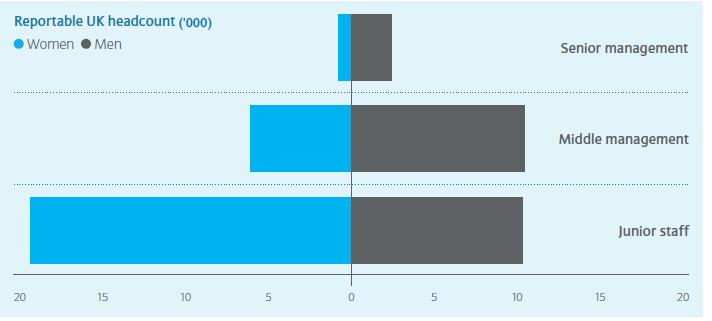

Ok, so now let’s look at banking. Barclays is a classic illustration of how the pay gap is prevalent in large corporations more generally. The graphic below shows the headcount in Barclays and you can see right away there is a skew right across from junior to senior staff of where women sit within the organisation; a higher percentage of women sit in junior positions; much lower in senior positions.

This results in men on average earning more as they occupy more senior posts. Why? Well, presumably this is due in part to ‘sticky floors’ and ‘glass ceilings’. Women get blocked and get stuck en-route to senior positions, or they drop out.

What’s the problem?

Well, this depends on whom you ask. Organisations become very defensive quite quickly on this topic. Ostensibly, scrutiny about the gender pay gap appears to be about fairness, that is it isn’t fair that a person should be paid less in society just because of their gender.

Fair enough. However, the underlying issue is really about career progression and inequality of opportunity. Sticky floors and glass ceilings. Viz: women earn less is because they do not progress as far up the career ladder. That’s not so easy to unravel.

I hate to say this but there is also a strong case for discrimination here. For example, the Equality and Human Rights Commission (ECHR) found that one in nine new mothers were either dismissed, made redundant or treated so poorly they felt they had to leave their job. This results in reduced work experience and lower wages if and when women return to work.

Male-dominated corporate and workplace cultures are on trial here. Beyond fairness and discrimination, companies may be missing a trick as there are positive business reasons why they should encourage women to progress to senior positions.

According to McKinsey, gender-equal companies outperform their unequal competitors by 15%, and EBIT increases by 3.5% for every 10% increase in boardroom equality. Women on boards is good for business!

But why, then, if equal opportunity pays dividends, have we struggled to solve this issue? Many women want to take a hiatus from their careers in order to look after their children and, anecdotally, some women feel pressure to stay at home after childbirth more from their wider family and friends, or in the way they come to a decision with their partner, rather than this being forced on them by employers.

It may mean the pay gap will never close, but if choice is part of the equation, some women will choose family before career. If the analysis and solution is likely to be multi-faceted, then, perhaps one thing that deserves our attention is how to get upstream of all this?

Here, the research gets really interesting.

Children and Gender Inequality: Mum’s the word

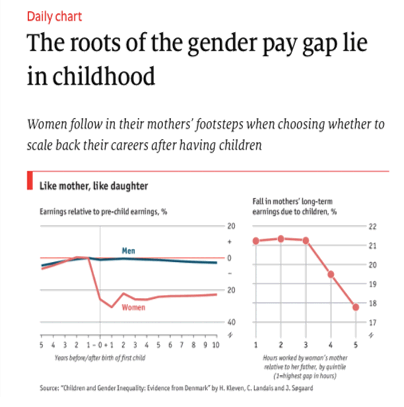

A study published in January 2018 by Kleven, Landais, Søgaard, from Princeton, LSE and the Danish Ministry of Taxation, respectively, found that substantial gender inequality persists in all countries and most of the earnings inequality between men and women over their careers is explained by women having children.

The key conclusions are:

- Having children creates a gender pay gap of about 20% in the long run

- The factors explaining this are labour force participation, hours of work, and wage rates in equal amounts. These issues are described as “child penalties”. The report shows that the fraction of gender inequality caused by child penalties has increased dramatically over time, from about 40% in 1980 to about 80% in 2013

- Key factors are type of occupation, promotion to manager level, sector, and the family friendliness of the firm for women relative to men.

- An explanation for the persistence of child penalties is that they are transmitted through generations, principally from parents to daughters consistent with an influence of childhood environment in the formation of women’s preferences over family and career. So, the daughter of a stay-at-home mum is more likely to be a stay-at-home mum.

The chart above illustrates that the earnings gap is linked to having children and the really interesting part is the causal claim that because women tend to follow in their mothers’ footsteps, the root of the gender pay gap lies in childhood. This is the kind of great social science that raises as many questions as it answers, which is the nature of a complex issue.

What’s the solution? (And who is responsible for it: Government, Employers or Schools?)

So, given that traditional roles of men and women in the family have persisted for centuries, and these cultural norms and expectations place a lot of pressure on women to be the main child carer after birth, we shouldn’t expect there to be a quick fix solution to this. But whose problem is it to solve?

The tendency with this kind of ‘big’ difficult problem is to expect government to solve it. But government’s rarely, if ever, solve issues on their own. In the view of the Fawcett Society, making the problem one for employers and corporations to have to solve is a ‘game changer’. So, from April 2018 making all companies with more than 250 employees have to report their gender pay gap will have the effect, so the argument goes, of ‘naming and shaming’ those who have the widest gap to do something about it.

But to an extent we’ve already seen this policy fail to work when it comes to UK plc. The UK has a relatively wide pay gap compared to some other countries, such as Iceland, Norway Finland and Sweden, who are in the top 5 for the lowest gender pay gaps. In Sweden, for example, the pay differential is 13%. They promote shared parenting and rules requiring mothers and fathers to take three months’ leave each for childcare.

True, Theresa May has called for more fathers to bear their share of parental responsibility and the burden of child care, especially in the early weeks. But if this is the crux of the issue, what kind of nudge would have a real bearing on which partner steps back from work? In the UK, it is women who step back to prioritise the family. We know this. But are we ashamed by it to change it?

Whatever initiatives the Government design, the impact will take a generation to effect. The nurses of today aren’t suddenly going to down tools and retrain as doctors, so the pay gap will persist for some time. Companies too have a supporting role to play.

Clearly, as the example of the Nordic countries shows, government initiatives can make a difference. But whatever policies we design at government level to try to influence cultural norms and expectations, the impact will still take a generation to have effect. The nurses of today aren’t suddenly going to down tools and retrain as doctors, so the pay gap will persist for some time. Companies and employers, then, must also have a vital supporting role to play.

Naming and Shaming the Corporate Bad Boys – will it work?

Is the Fawcett Society right to say this is a game changer? Let’s look at the facts. What’s emerged is that some of the biggest reported pay gaps are at well-known branded companies, such as Ryanair, JP Morgan, Apple, Macquarie and Boux Avenue. These are companies with a reputation to protect, and companies who will not want the next generation of bright young graduate recruits, whether women or men, to get a bad impression. So, lots of companies are now starting to launch initiatives to ‘deal’ with the pay gap.

Examples include:

- Fast-tracking: For example, The Guardian News and Media have promised to fast-track women to senior management positions

- Mentoring programmes; the 30% Club offers mentoring of women into senior positions

- Personal objectives of Board members to deal with diversity and gender pay. Virgin Money match any flexible working arrangements new hires had in a previous job and also raised pay for shared parental leave to the same rate as maternity pay to encourage more men to take it. The bank also found that about half the pay gap was due to an underrepresentation of men at entry level and has renewed its focus on attracting and retaining junior male staff.

- Organisations have set up programmes to help to improve the retention and pull-through of women to senior level, such as Bank of America’s “Pathways to Progression”

- A number of companies have committed to employing more women in senior roles ‘within 5 years’. Who’s going to be checking on that?

Business schools, such as Harvard and INSEAD, have also set up Women in Leadership Programmes to encourage and support women into senior roles in business. So far, so good.

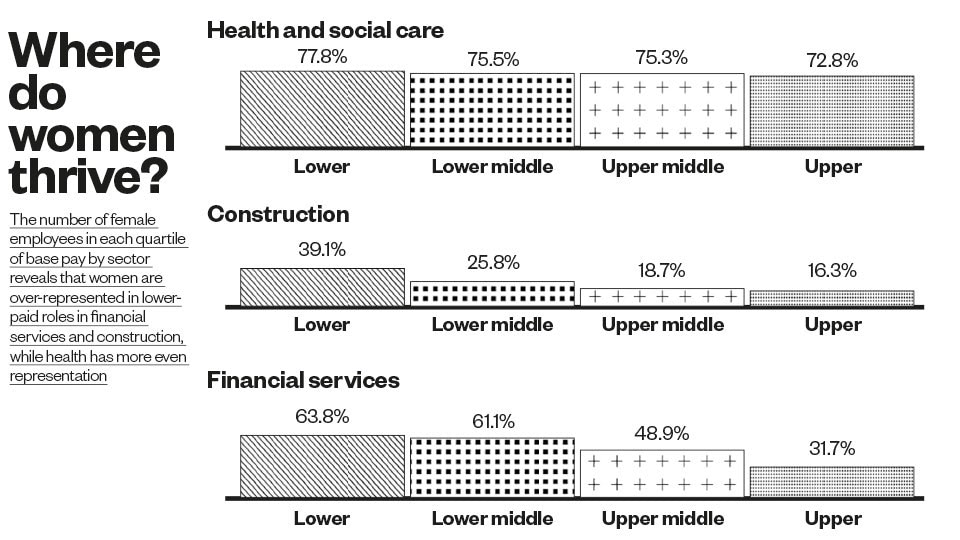

But when we drill down into the stats a bit more, we find that the gap varies hugely depending on the industry. Construction and Financial Services have the widest gender pay gaps. Compared to the Health and Social Care sector, women in Construction and Finance are unevenly represented across the pay scales: as the chart below shows, it’s all downhill.

Another Brick in the Wall; How Kloodle can tackle the Gender Pay Gap at school

The pressure to conform with societal and family expectations is engrained early in life and the gender pay gap starts with education. These influences mould attitudes which are culturally hard-wired, and it is difficult to break that mould especially as it is reinforced by parents, TV and social media. As a result, many women take careers in caring, teaching or part-time roles, partly driven by social norms and pressure to balance work and family life and, although these careers may involve a high level of cognitive and social skills, they are less well-paid.

Yesterday (16 Jul) new research from The Pipeline – which trains women for senior roles – revealed that progress on gender diversity at the top of Britain’s largest listed companies has stalled for the past two years.

Anne Sheehan, Enterprise Director at Vodafone UK, comments on the importance of nurturing female talent in STEM to address gender diversity issues:

Anne Sheehan, Enterprise Director at Vodafone UK, comments on the importance of nurturing female talent in STEM to address gender diversity issues:

“When I think about the lack of gender diversity in businesses today, I don’t think of just senior leadership. If we are to foster diverse talent to reach the top, I think there is a standout opportunity around STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) subjects in particular. I believe we can remove the mystery around STEM subjects for girls and young women still in education; and encourage them to feel more excited and curious about these subjects. This April, we partnered with Girls Talk to launch the next stage of our STEM mentor scheme which provides support, skills development and career assistance to girls studying STEM subjects.

“As Vodafone’s first female UK Enterprise Director, I’m excited to be part of a great movement to encourage young girls and women to explore their professional potential in ICT. Technology sits at the heart of incredible change and opportunity for UK businesses; I think it’s our responsibility to inspire future generations to become technology leaders regardless of gender or background.”

If we want the construction industry to become more gender equal then we need to see how characters like Bob the Builder, for example, instil gender stereotypes early on.

Joanne Frogatt, who plays Wendy, formerly Bob’s assistant, says:

“I think it’s really important for young girls growing up; from pre-school, nursery school and primary school, to be exposed to women in roles that aren’t traditionally women’s roles.

“It’s great for them to see women at the forefront of different positions, and it’s great that in Bob the Builder it’s a building profession and girls can see that women can be electricians as well.”

Here at Kloodle, we agree with Wendy, and support her promotion from assistant to electrical engineer, assistant to business partner, and go further by demanding that whatever pay gap exists between Bob and Wendy is closed!

Despite boys and girls across the country generally having access to the same choices and opportunities, gender stereotyping is already prevalent at age 7, according to the Drawing the Future report published earlier this year. Based on a survey of over 20,000 children, where boys want to go into male-dominated professions, such as engineering and science, girls focus on nurturing and caring professions, like nursing.

We see this reflected in subject choices at GCSE, too, where more girls opt to study ‘art and humanities’, such as modern languages, design and art, whereas more boys opt for STEM and IT. This then flows through to A level, university and ultimately into career choices, which are generally lower paid for women than for men. So, there’s a causal chain linking early years’ gender stereotyping with fewer girls studying STEM or technical subjects at GCSE and A level and women once they enter the world of work gravitating towards less well-paid careers generally, compared to men.

At Kloodle we understand that broadening the horizons of children about their future career opportunities, and the consequences of their choices, needs to start early. Our approach is to try to influence behaviour through early ‘nudges’ that encourage children and young people to develop skills based on their own interests and aptitudes, independent of gender.

This is where the input of the teacher is crucially important and with their guidance the pupils can talk about the subjects they enjoy and record their skills. The skills can be clearly linked to career pathways and give aspirations to young people. So, for example, being good at geography, maths and problem-solving, could be a good combination to be a future pilot.

By creating evidence of different possible career paths open to all children we are helping to reverse engineer gender stereotyping bias, celebrate counter-stereotypical role models, and promote the diversity and social mobility that our economy needs to help us all thrive. And what we aim for this way is for more girls to decide to become pilots rather than cabin crew.

Are we being idealistic? Maybe. But brick by brick, we see our student profiles are helping to dismantle gender stereotypes which underpin the pay gap as it exists at present.

At any rate, our aspiration at Kloodle is that if a future gender pay gap persists among young people who’ve used and benefited from our careers input, it will do so in either direction, not because of a causal link based on inequality, but randomly so, based on positive choice.

Neil Wolstenholme, Chairman, Kloodle

Copyright © 2018 FE News

Responses