How well is post compulsory education preparing people for the distributed future of work?

Kitchen conversations, car parks and office keys no more.

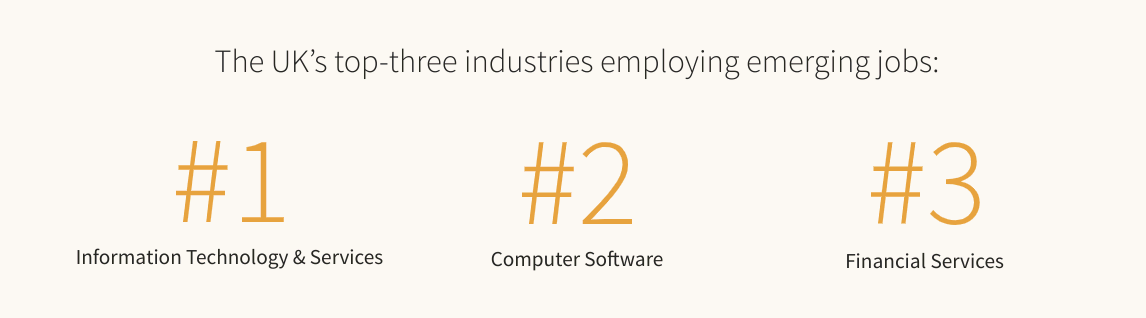

According to the LinkedIn Emerging Jobs Report for the UK, the top three emerging roles are:

- ‘Artificial Intelligence Specialist’

- ‘Data Protection Officer’

- ‘Robotics Engineer’

Whilst the top three industry sectors for growth are:

- Information Technology Services

- Computer Software

- Financial Services.

Additionally, as at the time of writing there are a total of circa 30 million companies active on LinkedIn with circa 20 million vacancies looking for a candidate.

There’s a common theme running through all this and it’s not just the obvious one in regard to their technology focus.

Rather, my contention is that they are all untethered location independent activities and industries, and they reflect strategic shifts that have been underway for quite some time, arguably back to 1991 when this thing called the internet arrived (at least the Sir Tim Berners-Lee version did).

When you mix the digital forces shaping our world with the Covid 19 pandemic we can see a seismic shift taking place and it’s having profound implications for how we live, learn and work. My contention is that the pandemic hasn’t caused many of these trends in itself but rather it’s accelerated trends that were already taking place (hence the fastest growing roles on LinkedIn were already location independent long before the Covid 19 pandemic arrived). So in a digitally connected location independent world where people don’t travel to find work because the work travels to find them, the question for educators is how well are we preparing students for the distributed and hyper connected industries they will join?

I suspect 2020 is one of those years that will, in time, become the stuff of legend.

I suspect 2020 is one of those years that will, in time, become the stuff of legend. In the middle of the 2030s parents will tell teenagers stories of how we all stayed inside for a year whilst preserving toilet paper to unimpressed and confused ‘quaranteenies’. On a serious note some of the changes that were accelerated by the pandemic are already clearly sticking. Distributed ways of working in business were already accelerating before the Covid 19 pandemic with the likes of Forbes and Hubspot both reporting that 30% of workers were already remote workers in 2019 and that between 2010 and 2020 there had been a 400% increase in the number of people who work remotely at least once a week. In April of 2020 Google reported that three million new users of its online meeting technology Google Meet were being added daily and for its education technology ‘Google Workspace for Education’ tens of millions of new users were added in months as the world moved online whether it wanted to or not. Some of these changes are starting to become a more permanent feature of the landscape we are in.

Cloud based technologies the world over were providing the freedom and flexibility to learn and teach irrespective of lockdowns (where people had access to the internet, a device and an appropriate space to learn in of course, which many didn’t). My contention is that this rapid change, as is often the case with change, had many unintended consequences. One of the more positive unintended consequences is that students are now far more familiar with the nature of working online as part of a distributed team than they otherwise might have been. Online lessons and meetings have become just part of the normal daily rituals of how we live, work and learn. There are many benefits to this approach from lifestyle, to helping to address some of the challenges of the climate crisis and wider, but purely from an employment perspective this experience may help students more than we currently realise.

In our company the team is distributed globally with colleagues in Finland, Sweden, the UK and wider all working collaboratively through technology to deliver products and services to more than 30 countries. Some of the people in the team may never have met in person yet work together daily on projects that bring together a diversity of people irrespective of location or their ability to travel. This is not unusual. In fact millions of people in the UK work in this way, and working in a distributed way is increasingly moving from the periphery to the core of business models because it makes sense for both the planet and for the financial bottom line. It’s a trend that will only accelerate, just as the internet itself did.

Photo via Markus Spiske

On an almost weekly basis we are seeing news reports of large companies moving to more of a hybrid working model with profound implications for cities as we know them now. My contention is that perhaps a smarter city actually isn’t one? What gave rise to cities as we know them now was, arguably, legacy reasons requiring humans to be in proximity to activities and wider resources but for many roles (and most of the higher value ones) this is no longer a prerequisite.

In the digital age, conventional business models are turning upside down and education is also no different. For example I have recently completed a course at the University of Cambridge yet I never visited the campus. I did pay the university a tidy sum of money for the privilege though, and in return I benefited from the flexibility of studying online in a way tailored to a busy lifestyle that would have prohibited other more conventional ways of studying. Hybrid working is core, not peripheral now, and curriculum design needs to reflect it also.

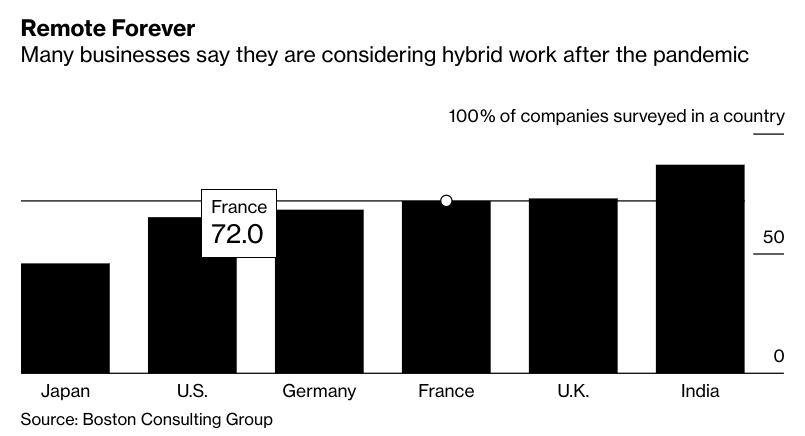

Shift to hybrid working models

For example in a recent survey conducted by the Boston Consulting Group in the UK alone more than 50% of the businesses taking part indicated a permanent, not temporary, shift to hybrid working models. The commercial reality of this is straightforward in some ways. Cloud technology supports more efficiency, lower operating costs and greater productivity in turn supports relatively sustainable competitive advantage when set against those competitors who insist on working in the way they used to. Those who follow the path of the latter will suffer in a relative sense when set against those who do not, not least because organisations offering the best experience will attract the best talent. Going back to the university course I mentioned, most institutions were not offering comparable courses with the same degree of flexibility tailored to the market. They appeared to be systems driven rather than market led. So the money went elsewhere. Agile ways of working are the future.

These trends were brought into stark focus very quickly as the Covid 19 pandemic arrived in early 2020 and to get a sense of how leaders were approaching these challenges we gathered a number of senior leaders from the word of education together to share insights at that time. The output of those conversations was published as a report titled ‘New, Next or Never Normal?’ and one of the key messages back then was the recognition of massive disruption to business models that would be ongoing, not temporary, and with it the need to develop agile business models along with new pedagogical approaches. As the famous sports commentator Yogi Berra once said “it’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future’ but looking back to the disruption of 2020 that one is already starting to feel about right as the commercial sectors are already showing. It’s a permanent shift and the change is accelerating.

Zoom forward to the present day and leaders are now increasingly assessing the extent to which the emerging themes around them are embedding as a permanent change in behaviours and associated expectations. The hybrid world of work and learning has significant implications for offices and campuses and a radical reimagining of their purpose and place and in our world is needed now, along with a review of curriculum design as new pedagogies will be needed also.

Do we need physical campuses in post compulsory education at all?

Perhaps we should ask if we need physical campuses in post compulsory education at all? It’s a hot topic right now. I suspect that financial factors alone will maintain and accelerate the trends shaping our world regardless of whether we like it or not. You can’t un-invent the internet and the competitive advantages it can offer. However my contention is that whilst there is a place for the physical campus, just as with nostalgia it’s not what it used to be. A bold vision is needed to reimagine the role and purpose of the campus so that when people do meet together in a locality it is with specific intent, rather than from habit.

Agile and highly personalised products and services delivered in a sustainable way should dominate thinking about our world of learning and work. Right now, the forces shaping it have been accelerated by the crisis of the Covid 19 pandemic, but in time they will be replaced by another crisis that is shaping our world in the same way but for different reasons, namely the climate crisis. Both of these crises have things in common. Both are radically transforming how we live, work and learn, but where they are different is that only one of them is relatively temporary. The climate crisis will remain long after Covid and with it the necessity to apply insights and lessons from what worked better during the pandemic crisis in a way that helps us to secure a more sustainable collective future to deal with the climate emergency. Audit Committees pondering risk register scores must now contend with the threat of a future pandemic also, so there is no going back since you have no defence against a reasonably foreseeable risk. Having an agile platform on which to maintain and deliver your services in education isn’t optional now. In fact for the compulsory education sector in 2020 it became a formal legal duty imposed by the UK Department for Education (DfE).

As organisations adapt to continual disruption both emergent benefits and risks will of course emerge. On the latter point, cybersecurity will also become an ever greater concern as hybrid working develops. In a report from Cisco called the ‘Future of Secure Remote Work’ a majority of respondents to a survey highlighted the increasing cybersecurity challenges of managing highly distributed teams. Cybersecurity now requires far greater strategic planning and resources than ever to protect both business critical systems and data as workers increasingly transition from the campus to the cloud. Get it right and the benefits can vastly outweigh the negatives.

A recent survey by HR consulting firm Mercer concluded that for over 90% of employees they surveyed productivity was higher when working remotely during the pandemic than before. Of course productivity is one thing, wellbeing and health quite something else. On that point educators across the world have shown the way sharing insights and lessons on wellbeing and health in a world of hybrid learning, but I question whether the same focus is being applied to digital competencies. I recall one educator saying to me in 2020 “we hear a lot about digital natives so we assumed young people could just flip their learning online. That was wrong”. I question whether we are preparing young people to maintain healthy, happy and safe lives in our always online world in the way perhaps we need to. Digital skills in their broadest sense from how to stay safe online to knowing how to source credible information, operate more sustainably and how to be effective as part of a distributed online team are all part of the fabric of our daily lives now, and these factors will only accelerate. Digital literacy is as important as numeracy and literacy now and should be given the same status in our education system.

Image via Matt Ridley.

Post compulsory education system needs to be learning driven, not process led.

From the high street to the campus, the radical amplification of the disruptive forces of the pandemic, the climate crisis and technology is shaping our world and fundamentally changing relationships with learners also. For example I recently asked a number of college leaders what their biggest challenge was and the answer was getting students to return to the campus. My question was, why are you forcing them to? The next challenge I suspect will be convincing students to start in the first place if organisations insist on them travelling to campuses to study in conventional ways. For some that will be the right approach, but for many, it won’t. Our post compulsory education system needs to be learning driven, not process led.

My contention is that the future of post compulsory education may feature less kitchen conversations, traffic jams and time spent searching for a parking space on the way to the office and more time spent teaching and learning. This will be enabled by more flexible, personalised ways of working also aligned to creating a smarter and more sustainable planet. Much of this in turn will be enabled by cloud technology and associated digital disruption arising from AI enabled systems, VR and wider technologies. To make the most of these opportunities many changes will be required and won’t happen overnight as it will require new approaches to investing in digital infrastructure, training and development, as well as radically reimagined workspaces. However, as students progress onto their future destinations it is becoming increasingly essential for educators to have prepared them for the world of work as it is evolving now, not how it once was, because there’s no going back.

Jamie Smith, Executive Chairman, C-Learning

Responses