It’s time to bring back Skills Accounts to kick start Lifelong Education and Training

The UK has a longstanding problem with low levels of productivity and skill utilisation. Adult Skills Accounts, done properly, could stimulate demand for education and training among the working population.

Skills accounts have been around, in one form or another, for a long time. In the UK Individual Learning Accounts were introduced by the Labour government in 2000 and subsequently withdrawn a year later under a cloud of administrative incompetence and accusations of provider corruption. Scotland and Wales have since reintroduced them but in England they have been piled on the prodigious ‘tried and failed’ scrapheap of badly implemented policy.

Lessons from Singapore’s SkillsFuture Credit system

The OECD’s review of learning accounts identified renewed attention from policy makers in many developed countries as the rise in non-standard work and the fragmentation of careers present new challenges for both re-skilling and upskilling. Among the international evidence Singapore’s SkillsFuture Credit is the most commonly cited. This programme was implemented nearly 10 years ago and provides $500 (equivalent to £300) for every adult aged 25 and over, to be used for eligible skills-related courses. The credit, effectively a ‘voucher’ scheme, can be ‘topped up’ and carried forward from year to year.

Adult Skills Account

Our recent paper, supported by Staffordshire University, develops the concept of an Adult Skills Account to help stimulate participation in education and training among the working population. To provide a pathway to continued and higher education, including the take up of loans such as the Lifelong Learning Entitlement.

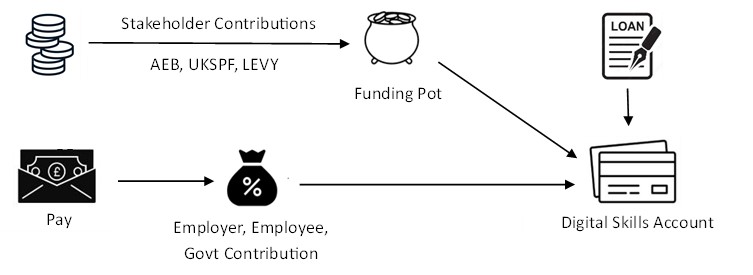

We make the case for a contribution scheme, similar to National Insurance or workplace pensions, and administered through a payroll enrolment system that can help share the cost of training between employee, employer, and state. This would provide a digital record of learning and accumulated credit, as well as financial contributions. The account would be portable – tracking the individual from one job, or education institution, to another.

It could also be topped-up with additional funds, including loans and grants, as well as other sources of public funding. The potential to ringfence or pool local funding sources (such as LSIF Funding, the Shared Prosperity Fund, Adult Education Budgets, and a reformed Apprenticeship Levy) could also be considered. Implementing such a scheme at the regional level would be within the gift of a Mayoral Combined Authority.

Based on the median salary of £26,000 per annum, an employee would be expected to pay Class 1 National Insurance of approximately £1,343 in the tax year 2024/25. An education contribution of 1% on the total annual wage would deduct a further £260. If this was matched on a pound for pound basis, by both employer and state, this would equate to £780. This is broadly equivalent to the cost of a 10 credit microcredential – assuming fees for 10 credits are proportionate to a full bachelor’s degree, of 360 credits, with tuition fees of £27,750 in England. This would be within the price range of many microcredentials currently on offer, via FutureLearn or the Open University.

Bite-sized training at a bite-sized price

This relatively small amount of funding could be sufficient to help employers and employees purchase quality assured bite-sized training at a bite-sized price. Enabling workers to build and stack credit over time, while stimulating demand for loans and larger units of learning. This is not a systemic solution to the problems of student finance or funding for the wider tertiary sector. Rather it is a modest form of bridging capital that can kick start lifelong education and training among the existing workforce, while allowing more employers to start investing in skills. This said, a tripartite funding mechanism could feasibly be scaled up to help fund the repayment of loans for full qualifications including degrees.

There are approximately 30 million people aged between 25 and 65 in England. A universal entitlement of £300 per person for this age group would cost £9bn. Given the state of the public finances and Labour’s commitment to stick within current spending plans, if elected, investment on this scale is unlikely. However, with an opt-in scheme not everyone will choose to take up the fund, while focussing on priority sectors and occupations will limit the scope and make skills accounts more affordable to Government.

The evidence from Singapore is instructive. Last year just 10% of all eligible employees choose to use their credit, the majority citing a lack of time and the opportunity cost of training rather than earning. If 10% of England’s workforce were made eligible for such a scheme it would cost the state less than £1bn and pump-prime an adult’s skills revolution, as the Skills and post-16 Education Act was meant to do. It could provide the necessary stimulus for a new market in adult education and the pathway towards the Lifelong Learning Entitlement, which as it stands makes no provision for microcredentials or any unit of learning below 30 credits.

UK also has a growing problem with skill utilisation

The facts are stark. Since the financial crisis economic growth has flatlined while productivity continues to lag other nations. The compared to other European countries. A third of all graduates are in low-skilled jobs reflected in a falling graduate wage premium. Meanwhile underemployment is an increasing concern in a changing labour market as growing numbers are working on zero-hour contracts. Employer investment in training has fallen by nearly 30% over the past 20 years as adult participation in education and training has plummeted.

We need a flexible skills system that can respond to these challenges and drive productive growth through the whole economy not just in selective industries or in the southeast corner of England. We need something that can meet the skill needs of the whole working population. And we need a funding mechanism that can facilitate this. Adult Skills Account could be an important step in this direction.

Mark Morrin, is a Research Associate with the Lifelong Education Institute

Responses