The state of higher education at the end of 2023

The end of 2023 is a good moment to be addressing the state of higher education. We have witnessed considerable political turmoil, marked by a major reshuffle and the current rows about migration, plus we stand on the cusp of an election year: the next election has to occur by January 2025 and it will almost certainly occur during 2024.

HEPI, like everyone else across education, has had a particularly busy year.

So let’s try and take stock of where we are on a range of higher education policy areas.

1. The Office for Students

First, England’s Office for Students. We have just had their response to September’s excoriating House of Lords’ Industry and Regulators Committee report. The original report said the OfS’s ‘approach to regulation often seems arbitrary, overly controlling and unnecessarily combative.’ The OfS’s response meets the Committee halfway, committing ‘to continue to reset our relationship with the sector we regulate to improve the effectiveness of our work.’ Time will tell.

The Westminster Government have responded to the House of Lords Committee’s report too, but their response is so carefully worded, it is not worth much of people’s time – even though it does provide yet another reminder that, unlike the general approach towards schools and despite the unfairnesses in higher education access funding, ‘the government is completely clear that we should have the same high expectations for all students, regardless of background or circumstances’.

The lack of substance in the Government’s response tends to confirm, for me, one of the common misunderstandings of modern British politics, which is the idea that Select Committees matter a great deal, when – in general – they do not.

To date, the OfS has appeared to have few friends and pretty much everyone is agreed that it has often got the tone of its communications with institutions wrong. Moreover, its reviews always seem to take far longer than anyone initially expected – we are currently, for example, waiting for:

- the results of the (almost) three-year long investigation of the University of Sussex on ‘whether or not the university has met its obligations for academic freedom and freedom of speech within the law’; plus

- 53 ‘pending’ Teaching Excellence Framework results, which are meant to be out before Christmas; plus

- the reports on many of the ‘boots on the ground’ investigations into quality, originally launched back in May 2022, which were due out in the summer.

But there is another side of the argument too. It was perhaps naïve to think the gentle ways of the old Higher Education Funding Council for England (Hefce) would persist once we had a market regulator. No one expects mobile phone network providers to like Ofcom or the water companies to like Ofwat. So why did we ever expect higher education providers to like the organisation that is still, very occasionally, known as ‘Ofstud’? The answer to that question, of course, is that we expected the Office for Students to resemble more closely the ways of working of its predecessors bodies, like Hefce and the ancient University Grants Commission. But the older bodies were funding bodies that could persuade through ‘the power of the purse’ where as most funding for teaching and learning now comes from the Student Loans Company or directly from international students’ fees.

The number and range of jobs imposed on the Office for Students from on high is, arguably, unreasonable for the level of resources it has. I recognise it is easier said than done, but I urge Ministers to give fewer directives to the OfS and to rank more clearly by importance those that they do give.

Whether this happens or not, the OfS have a tricky year ahead. Perhaps most urgently, they need to clarify what they are expecting from governors, managers and students in relation to the active new duty to promote free speech on campus under the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Act (2023).

Since the new free speech tsar, Arif Ahmed, took up his role, he has performed some skilful positioning on his attitude towards how universities should respond to the IHRA definition of antisemitism and made one wide-ranging and interesting speech. But as the Middle East has flared up, the issue of protecting and promoting free speech in universities has become more challenging and issues are arising on campus right now – as we saw on the other side of the Atlantic in the recent Congressional hearing with the leaders of Harvard, Penn and MIT. Yet institutions are expected to wait who knows how many months for the new OfS guidance. I am not sure that is a sustainable position for much longer because the risk is that people who try to second guess the OfS’s eventual approach may get it wrong.

I know some people think that an incoming Labour Government will wish to sweep the whole edifice of the Office for Students away and there have been voices on the left and the right who have raised the end of the OfS as a real possibility. Perhaps that will happen, but I doubt it will be anything like near the top of the list of priorities for any new government.

When I worked on higher education policy for the Conservative Opposition prior to them entering office in 2010, we were often asked whether we would abolish Hefce. We did not have much desire to do so but we said that, either way, it was the sort of decision best left for a second term of office, after more urgent priorities had been tackled – and, indeed, the OfS was set up in the Conservatives’ second term. Perhaps this precedent does not tell us much but, for now, I am assuming that the OfS is here for a good few years yet. After all, as I have already noted, its make up reflects the way university teaching is now funded and neither major UK-wide political party is currently planning on changing that significantly.

2. Migration

Much of HEPI’s most influential work in recent years has been on international students. Working with others, most notably Kaplan (a HEPI Partner), Universities UK and London Economics, we have considered:

- the impact of Brexit;

- the tax contributions of those international students who stay in the UK to work;

- the expectations of international students in relation to student support services;

- the impact of the Graduate Route visa; or

- the enormous soft-power benefits of hosting so many people from other countries.

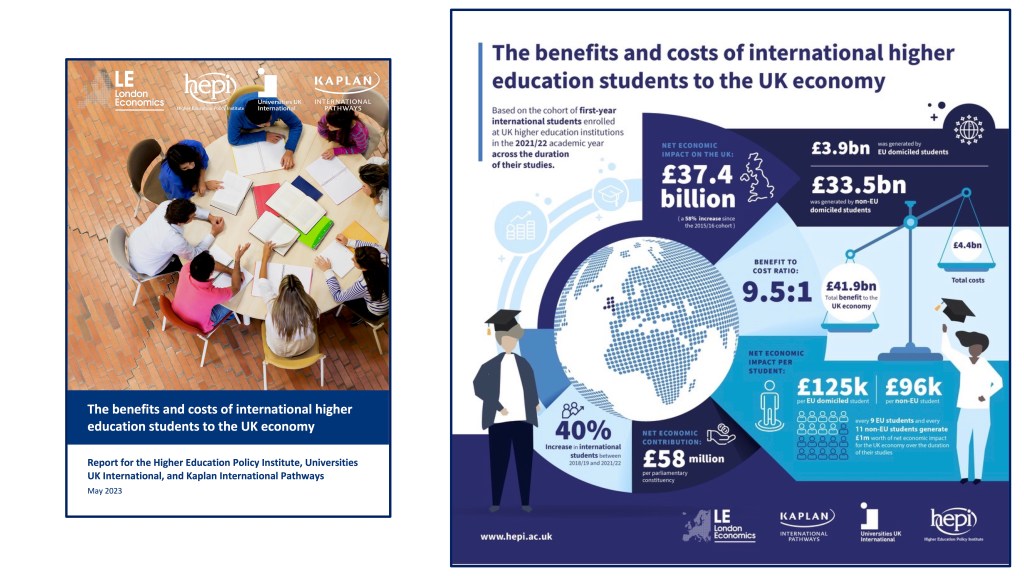

We have also (three times) calculated the economic contribution of international students. The answer is £42 billion and we have broken this down for each parliamentary constituency so that every MP and every candidate at the next election knows how beneficial international students are economically for their local area.

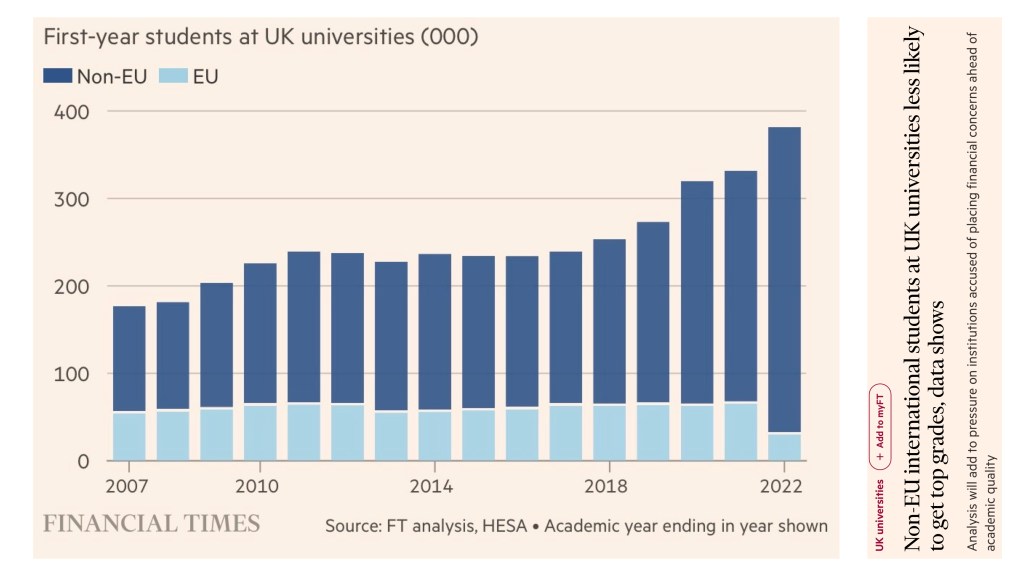

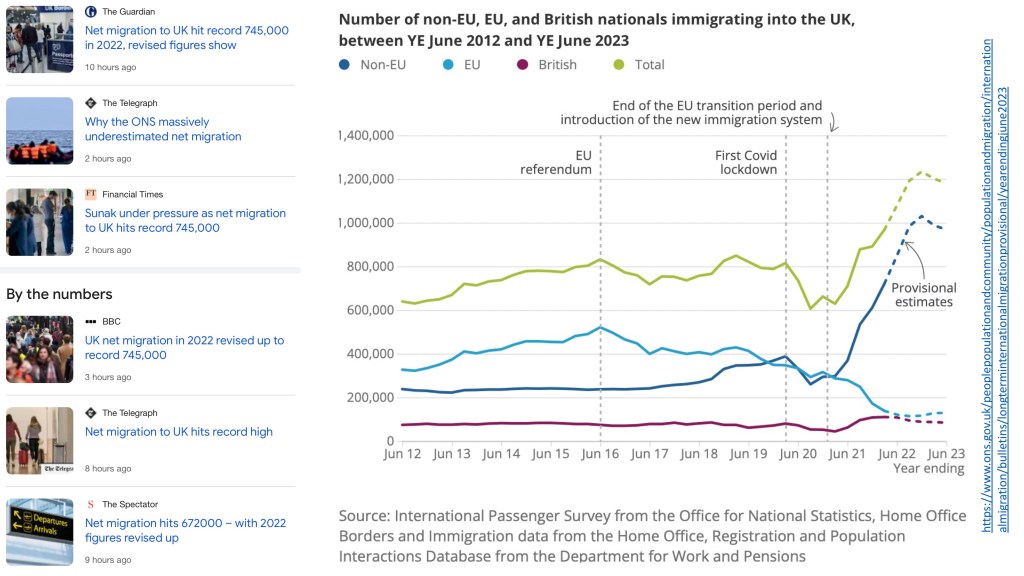

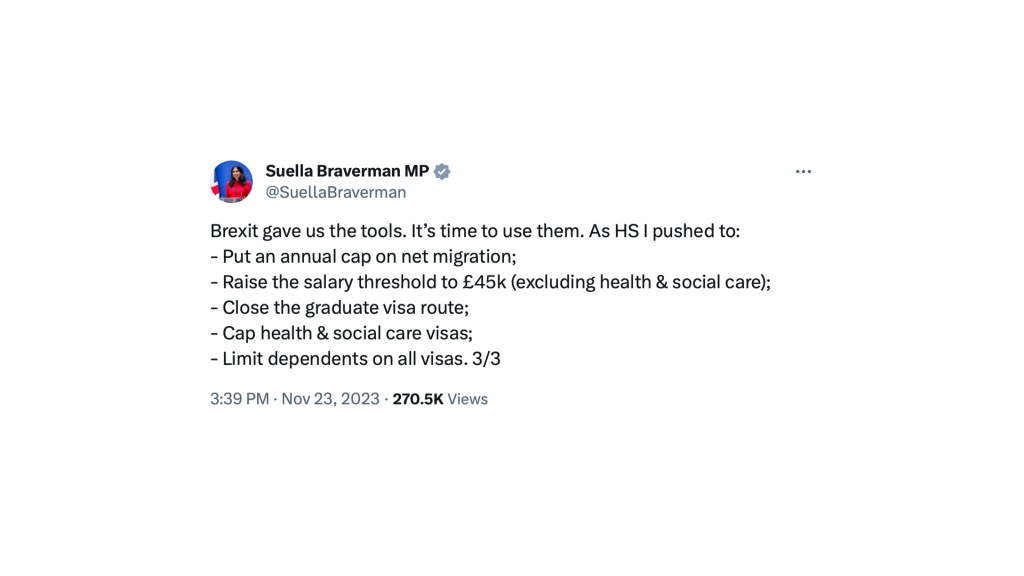

But the policy backdrop on international students has been like a roller coaster. To cut a long story short, the rules were tightened while Theresa May was Home Secretary, leading to a flatlining in the numbers while other countries forged ahead, and they were relaxed when Boris Johnson was Prime Minister, leading to substantial growth. One of Suella Braverman’s legacies is another recalibration in a more restrictive direction, with new restrictions on the dependants of international students on taught Master’s courses starting in January 2024.

I would rather the new rules on dependants were not happening. But I do understand why they are. The number of dependants coming with international students has grown eight-fold in recent times; we held an event earlier this year where a long-standing Labour MP who is normally a great friend of our sector talked about the challenges for his local public services, including primary schools which had international students knocking on their doors with an unexpected number of child dependants in need of support and an education.

However, there were better ways to grapple with this challenge, such as more sharing of information between the authorities and educational institutions on the number of dependants expected, thereby enabling more preparation. But the new rules are almost here now. And there is no chance of them being reversed in the foreseeable future: for example, when the changes for dependants were announced, Stephen Kinnock MP, the Shadow Minister for Immigration, told the House of Commons: ‘our entire Front-Bench team does not oppose these changes for masters students.’

The changes are already having a real impact. I saw a Nigerian news story the other day, which had a sub-heading that read: ‘Visa ban: Nigerians shun UK’. There isn’t any official data to back this sort of anecdotal evidence up yet, but other evidence is mounting up. For example, we recently published a blog by QS, which showed: ‘a considerable fall in the number of Nigerian offer-holders … of 40.5%.’

Given the changes on dependants are so new, and accepted by the main Opposition, I had been expecting some stability in this policy area as the next election approaches. But the recent unprecedented net migration numbers, the ensuing political row and the proximity of the next election have all combined to disrupt that expectation. And among other measures to reduce immigration, we now have a new review of the Graduate Route visa by the Migration Advisory Committee‘to prevent abuse and protect the integrity and quality of the UK’s outstanding higher education sector.’

This is not as bad as it could be, so long as the MAC does actually stick to looking at ‘abuse’ rather than – as many people fear – conducting a wider review of the existence of the Graduate Route. It is vital that we in the UK higher education sector constantly remind others of the limited terms of the announced review. Moreover, we have at least – so far – avoided the ideas of those who want to play divide-and-rule with our higher education sector. Suella Braverman, for example, has spoken to wanting to prioritise Russell Group university applicants when evaluating student visa applications. Nonetheless, the coming changes, which include a big 66 per cent increase in the NHS levy paid by international students and others, make us less competitive in the very competitive arena of international student recruitment.

3. Funding for teaching

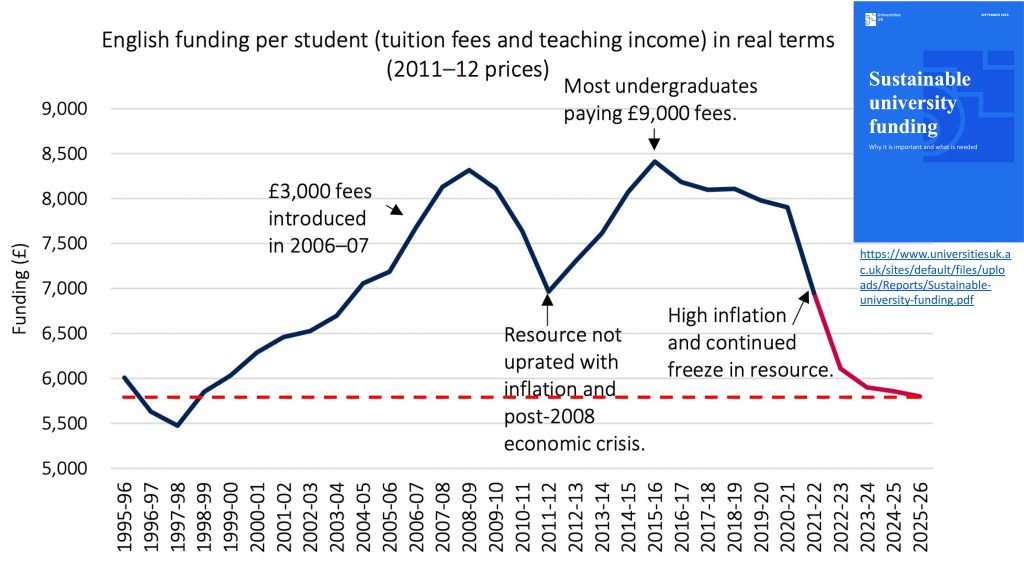

In my view, the current funding situation for universities is unsustainable but the funding system itself is not.

Professor Dame Sally Mapstone, who is both President of Universities UK and Chair of HEPI, recently pointed out that ‘collectively we incur an annual £1 billion loss in teaching domestic students’. The unit of resource for home students is already at its lowest level in real terms since the turn of the millennium and is continuing to fall fast.

Universities are generally charities but, like every other large organisation, they can only have so many loss leaders. There is now such a considerable shortfall in the income for teaching home students that there is growing evidence that home applicants are beginning to lose out to full-fee paying international students in the race for places, at least at the edges.

In my view, the sector missed a trick or two when it comes to lobbying on fees and funding. The first error was that, until relatively recently, it avoided offering a proper explanation of how fees are spent – yet, without this, policymakers cannot understand universities’ business model.

Five years ago, Jim Dickinson (who is now at Wonkhe) and I did our best to change this situation when, with two HEPI interns, we wrote Where do student fees really go? Following the pound explaining how the money is used and urging much more transparency.

Only once you have such information in front of you can you reasonably challenge Ministers on what it is they want universities to do less of when they oversee declines in real-terms funding. Discussing such matters has become even harder in recent times, thanks to the split in responsibility for teaching and research between two different government departments.

Our work on where fees go was not half as influential as we had hoped and most of our recommendations remain pertinent today. The final one of our 10 recommendations, for example, was: ‘Ministers should consider new income streams to cover the costs of valuable work that proves difficult to justify funding from student fees.’

Around the same time, we also did some work on cross-subsidies from teaching to research. This too was unpopular among some for shining a spotlight on internal institutional finances. I vividly recall being on the receiving of a fusillade from a famous Crossbench peer who is also an eminent academic at a research-intensive institution in London: he seemed to feel it was somehow inappropriate or dirty to expose the sector’s internal cross-subsidies to sunlight. But we have to do this sort of thing if we want Ministers to understand our sector’s financial situation. So I was pleased to see the recent ‘issue paper’ from UKRI on Research financial sustainability, which reminds us that ‘The deficit on research reached almost £5 billion in the 2021 to 2022 academic year, having risen 14% over five years.’

At HEPI, we will be looking at the different undergraduate funding options for the future in early 2024, as no doubt will others, in the run up to the next general election. The goal is to deepen understanding of the system we have as well as the pros and cons of the main alternatives.

There are a number of obvious possibilities on the table for England – for example:

- the Labour administration in Wales has introduced a system that is more generous for maintenance but similar for teaching;

- Jo Johnson has proposed in the House of Lords that institutions with a decent Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) rating should be able to increase their fees; and

- Bridget Phillipson, the Shadow Secretary of State for Education, has proposed focusing on a more progressive repayment system where ‘the government could reduce the monthly repayments for every single new graduate without adding a penny to government borrowing or general taxation’.

Any big change would take time: the Browne report was set up in 2009, Parliament voted for higher fees in 2010 and they started in late 2012. For now, it seems unlikely any Government is going to increase fees close to an election but it has been suggested to me by ‘sources close to Labour’, as journalists would say, that an incoming Labour Government could keep the system we have for now but find a bit of extra funding to push through the Office for Students to tide institutions over for a year or two. This would of course necessitate some changes to the recent Autumn Statement numbers on public expenditure.

For me personally, I do not think the system is broken. If only we were brave enough to link fees to inflation, with or without a link to the TEF, then we could get it back into equilibrium. Increasing fees in this way is a much less radical proposition than people think – remember, Tony Blair’s fees went up with inflation every year; we still talk about £3,000 fees, but they were only £3,000 for one measly year. Moreover, fees are not as electorally unpopular as you may think – the last party leader to win a general election while firmly opposing the introduction of tuition fees was, arguably, John Major over 30 years ago.

Really big changes to student finance tend to risk the return of student number caps, which would be an absolute disaster, especially as the number of school leavers is due to rise every year till 2030. The biggest benefit of the funding model we have is that it allowed us to remove the limit on places and that is the main prize worth retaining. (For information on this, see our work marking the sixtieth anniversary of the Robbins Report of October 1963.)

4. Maintenance

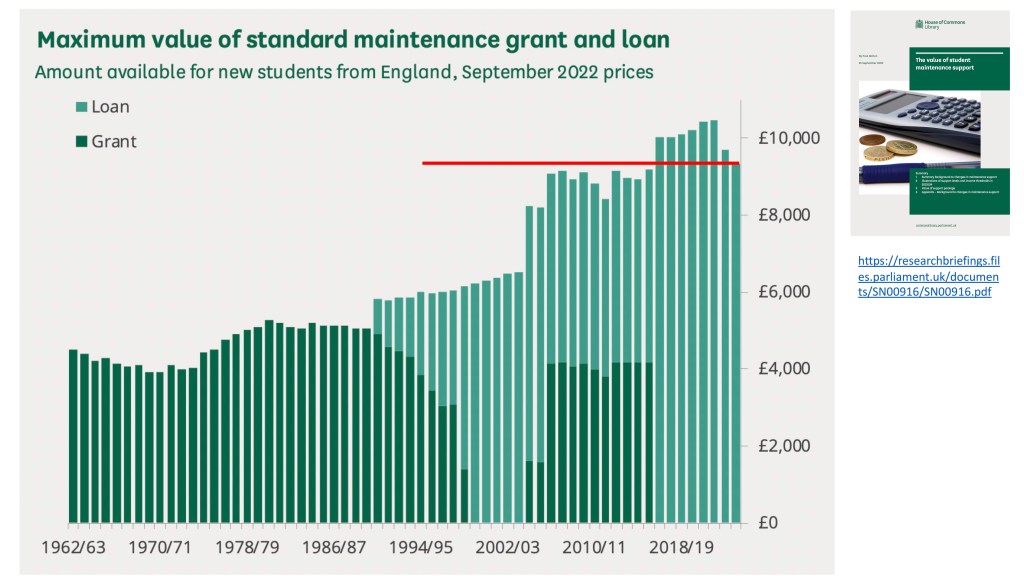

If universities’ resources for teaching and research are too low, then this is equally true of students’ living costs. The House of Commons Library has shown that the maximum maintenance support package in England is now at its lowest real-terms value since 2015/16. The Institute for Fiscal Studies has shown that, in the current academic year, students are entitled to borrow 11% less in real terms than they in 2020/21, which is £107 a month less for the poorest students.

Moreover, even though the amounts have been falling in real terms, the expectations on lower income parents have increased significantly, for the threshold at which parental support kicks in has been frozen at £25,000 in cash terms for 15 years, since 2008. Yet, according to the Bank of England’s inflation calculator, £25,000 in 2008 is equivalent to £40,000 today. That explains why, in a recent HEPI report on the ‘cost-of-learning’ crisis for students, we recommended raising the income threshold and then ensuring it rises at least in line with inflation.

We recently showed in another HEPI Report, produced with the student housing charity Unipol, that over the last two years alone, there has been a 23% increase in inflation (RPI) and a 15% increase in student rent, but only a 5% increase in maintenance support in England.

The rising cost-of-living relative to students’ incomes may well be part of the explanation for the softening of demand for higher education. UCAS’s new end-of-cycle data for 2023 shows a year-on-year drop in total acceptances, which includes a drop in UK 18-year-old acceptances and a fall in accepted international students, although the overall numbers are still higher than they were before the disruption of COVID. Other changes that could also be having an impact on demand include the tougher student loan repayment rules that took effect for those entering higher education in autumn 2023 as well as the tighter labour market, which makes employment a more feasible alternative than it was during the worst of COVID.

It is worth noting in passing that the softening of demand is not unique to the UK; it is also plaguing comparable higher education systems. Ben Wildavksy’s new book about the United States (which HEPI will be running a review of before Christmas) notes the impact of ‘uncertainty and anxiety about the market value of degrees, a strong public (and characteristically American) belief in practicality, the rising desire for inexpensive, short-term, job oriented credentials, and the cataclysmic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic’. We are told these have ‘combined to strengthen the push for BA alternatives.’

Back here, those who do enrol are not generally anything like the snowflakes you hear about; they are resilient and have responded to the shortfall in personal income by going out and finding paid employment in bigger proportions than ever before, as we have shown in the UK-wide HEPI / Advance HE Student Academic Experience Survey. But when the hours of paid work are high, this has an impact on academic studies as well as involvement in extra-curricular activities.

Policymakers cannot ignore the basic facts of life on students’ cost-of-living for ever or, if they do, non-continuation rates could surge.

5. The run up to the election

Six decades ago, back in 1964, Labour returned to office using the campaign slogan ’13 wasted years’. They may well try something similar this time around. Indeed, at the Independent HE Annual Conference the other day, Matt Western, the Shadow Minister for Higher Education, accused the Conservative Government of not addressing ‘sustainability in university funding’, of ignoring ‘the increasing number of 18-year-olds entering universities in the next decade’ and of disregarding ‘the importance of international students and the income and value they bring to universities.’

Such attacks focusing on the level of inaction may well resonate and stick and I understand why they are being made, but I am not sure they are strictly accurate. There has in fact been enormous change driven from Whitehall over the past 13 years, as I argue in a new HEPI Debate paper, whether it is:

- financial, such as the increase in domestic fees, the removal of student number caps and the increases in research spending; or

- structural, such as the replacement of the Higher Education Funding Council for England with the Office for Students and also the establishment of UKRI.

Other changes have included numerous tweaks to the rules on international students, as I have already discussed. So whether you like the changes that have been made or not, it would be hard to claim the successive centre-right administrations in post since 2010 have been asleep on the job. A lack of change has not been a problem.

So it strikes me as very odd that the party in charge seems to want to hide its biggest higher education achievements of the last 13 years – including the growth in the number of younger students and especially the proportion from tougher backgrounds – under a bushel, as it tacks towards those stick-in-the-muds who think we have too many students, too many universities and, overall, too much modernity and who seem to want to return to a cartoon version of the 1950s.

Where, for example, are the press releases from Tory Party HQ trumpeting the extra student places they have created, the unprecedented focus on the student experience and the additional research that would not have happened without the additional funding?

There are challenges on the other side of the political spectrum too because we do not really know enough yet on what Labour would do in higher education if they win – although, as Jess Lister of Public First has repeatedly and persuasively warned, higher education policy might not change as much as people are supposing.

So while, at one level, we seem to have something approaching a consensus between the two biggest parties in higher education policy – for example around fees, around student places, around internationalisation and around research funding – at another level both big political parties seem keen to emphasise the opposite and to retreat to caricatures where the left looks progressive and bold and the right looks regressive and timid. I am not sure anyone benefits much from this, and it does not encourage mature political discussions about post-compulsory education, but that is how it may remain between now and the next 2024 election.

I am often asked what the sector and individual institutions can do. Let me suggest three things:

- Tell a relentlessly positive story about what UK universities already contribute and constantly remind people that we are unlikely to make progress on the big challenges we face – delivering economic growth and productivity, tackling intergenerational inequities, making levelling up meaningful, improving public services and addressing climate change – unless universities are at the heart of the responses. Viv Stern and her team at Universities UK already do this very effectively but it is a task for the whole sector and not just its representative bodies.

- Reach out beyond the policymakers we know best to all those with an indirect interest in what we do. As an example, take the East of England, which is represented by 58 Members of Parliament, 86 per cent of whom are Conservatives. Yet Chelmsford aside, the three biggest areas for higher education in the East of England (Cambridge, Norwich and Luton) are among the mere 9 per cent of local constituencies represented by Labour MPs. Perhaps that will stand them in good stead if there is a Labour Government, but we need all sides of the House of Commons to understand our sector fully and so we need to engage with all policymakers and not just those that directly represent our sector.

- Think about some specific election-themed events you might run – how about hosting a hustings with local candidates aimed at staff and another aimed at students, with some spaces available for the general public at both? Or how about university leaders putting together their own election manifestos, as Professor Quintin McKellar, Vice-Chancellor at the University of Hertfordshire, did through HEPI in 2015 or as Professors Sir Chris Husbands, Sasha Roseneil and Adam Tickell have all recently done in a combined HEPI report launched at the 2023 autumn party conferences.

In terms of preparing for a possible incoming Labour Government, one area to look at is Australia. Of all the countries in the world, it is Australia’s higher education system that is closest to ours – and they tend to pip us at the post. For example, they introduced fees backed by income-contingent loans before we did, they shifted to an even greater degree to relying on international students to cross-subsidise (pretty much) everything else that institutions do and they removed student number caps a little before we did.

Last year, Australia veered left politically, putting in the first Labor Government since 2013. This new Government has sought a rapprochement between Canberra and universities through a once-in-a-generation review called the Australian Universities Accord. This is designed to ‘improve the quality, accessibility, affordability and sustainability of higher education’ and is grappling with two countervailing pressures with which we are familiar: the need for more highly skilled people on the one hand (with a prediction that 90 per cent of new jobs will need a tertiary qualification) but a declining interest in attending higher education on the other.

There are different views on the Accord process, with many welcoming it but some fearing it could lead to an unprecedented trampling of university autonomy – as a forthcoming HEPI blog by the brilliant Professor Andrew Norton of the Australian National University (ANU) will testify.

The final report of the Accord process is expected early next year but the recent interim report recommends:

- action on campus safety, on precarious employment contracts and on the quality of governance;

- moving way beyond 50 per cent higher education participation, to be achieved by putting a new focus on under-represented groups; and

- delivering more diversity among providers – calling for ‘a wider range of complementary institutions differentiated by their unique missions.’

In the 1990s, the incoming Blair Government’s reforms were heavily influenced by the system of fees and loans then in place in Australia. So my final parting thought is that, if you want to know what an incoming Labour Government might do to our sector, then it might be worth looking a little Down Under too.

Responses