How GCSE and A-level exams are marked – some consequences

Can perfectly correct marking result in ‘ambiguous’ GCSE, AS and A-level grades? Yes. This is how… And it happens much more often than you might think.

A recent piece in TES, How are GCSE and A-level exams marked?, gives a succinct, and accurate, description of how exams are marked and graded. That’s what actually happens. But what actually happens has some important consequences – consequences that are not immediately obvious.

Referring to a single question, the article states that “an examiner may award 13, 14, 15 or 16 marks, and all of these marks would be correct”. That is of course true, for everyone reading this knows that “it is possible for two examiners to give different but appropriate marks to the same answer”, to use Ofqual’s own words.

The consequences

One consequence of this is that the script might be given a total mark of, say, 64, 65, 66 or 67, all of which are correct.

Suppose that grade B is defined as ‘marks from 63 to 68 inclusive’. In this case, that script is awarded grade B, no matter which mark was given.

But if the B/A grade boundary is set at 65/66, then marks of 64 and 65 correspond to grade B, but marks of 66 and 67 to grade A.

This creates a most odd situation. Perfectly correct marks result in two different grades, with a single grade – either the A or the B – appearing on the candidate’s certificate. Whichever grade is awarded, the other might have been; either grade is therefore ‘ambiguous’.

Is it fair that a candidate’s grade is ‘ambiguous’, an artefact of the lottery of which examiners marked the script?

There’s another consequence too.

Suppose that the candidate is awarded grade B, correctly, from the correct underlying mark 65. If the school requests a review of marking, that will, correctly, identify no marking errors, and so confirm the original grade B. Even though other examiners would, totally legitimately, have awarded grade A.

Ofqual know this, but dismiss it: “It is not fair to allow some students to have a second bite of the cherry by giving them a higher mark on review, when the first mark was perfectly appropriate.”

Ofqual’s Research

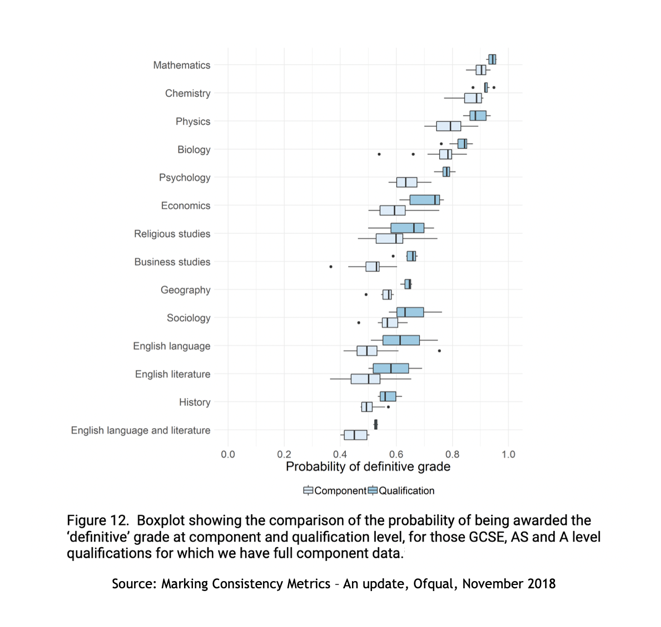

You might wish to think about that, especially in the light of Ofqual’s own research, published in November 2018, Figure 12 of which is reproduced here:

Please refer to the original for the details; let me note here that, for each subject, the key feature is the heavy black line in the darker blue box: for example, at about 0.96 for Maths, 0.65 for Geography, 0.56 for History.

Breaking down the research

If you subtract these numbers from 1.00, you get 0.04 for Maths, 0.35 for Geography, 0.44 for History. Those last numbers are important, for they are measures of the frequency of the delivery of ‘ambiguous’ grades in each subject.

Accordingly, the grades for about 4 in every 100 Maths scripts are ‘ambiguous’; about 35 in every 100 for Geography; about 44 in every 100 for History. ‘Ambiguous’ grades such that the (single) grade shown on a candidate’s certificate might have been different – perhaps higher, perhaps lower – had different examiners marked those scripts; different grades that cannot be discovered for there have been no marking errors.

This summer about one-quarter of all grades awarded are ‘ambiguous’

The overall cohort-weighted average across all 14 subjects is about 0.25, implying that, this summer, about one-quarter of all grades awarded – that’s about 1.5 million – are ‘ambiguous’. Given that there are only about 1.2 million candidates in England, on average, every candidate in the land has been ‘awarded’ one ‘ambiguous’ grade. But no students know which grades in which subjects. Nor can a challenge or an appeal identify them.

Conclusion

Is this what Ofqual’s former Chief Regulator was talking about when, in evidence to the Commons Education Select Committee, she acknowledged that grades “are reliable to one grade either way”(Q1059)?

Is this what Ofqual’s current Chief Regulator was talking about in her YouTube interview when she says “More than one grade could well be a legitimate reflection of the student’s performance” (about 9:19)?

Really?

So why is there only one grade on a student’s certificate?

How many other “legitimate” grades are there?

What is their “legitimacy”?

By Dennis Sherwood, campaigner for the delivery of reliable and trustworthy school exam grades

Dennis Sherwood is an independent consultant, a campaigner for the delivery of reliable grades, and author of the book Missing the Mark – Why so many exam grades are wrong, and how to get results we can trust (Canbury Press, 2022).

FE News on the go…

Welcome to FE News on the go, the podcast that delivers exclusive articles from the world of further education straight to your ears.

We are experimenting with Artificial Intelligence to make our exclusive articles even more accessible while also automating the process for our team of project managers.

In each episode, our thought leaders and sector influencers will delve into the most pressing issues facing the FE sector, offering their insights and analysis on the latest news, trends, and developments.

Responses