Britain is on its way to experiencing an unemployment crisis

Workers in labour-intensive and lower-paid sectors will be hardest hit

Before the onset of Covid-19 and nationwide ‘lockdowns,’ nearly one-in-five UK workers were in a sector that would be temporarily shut, a large share of whom were low-paid and had lower-level qualifications. And while many furloughed workers have since come back to work: as of 1st August, nearly four-in-ten workers in hospitality and leisure, and one-in-ten workers in non-essential retail, remain furloughed. It’s therefore unsurprising that many policy makers and analysts fears that employment in labour-intensive sectors offering in-person services will continue to suffer, especially after the Government’s Job Retention Scheme (JRS) comes to a close in October.

Policymakers will no doubt look to adult education and training as part of the solution – despite the fact that, in the round, adult education and training has been tilted towards workers with higher-level qualifications

Though the scale of the unemployment crisis coming down the pipeline remains to be seen (an uncertainty amplified by uncertainties in the current labour market data), it’s highly likely that the Government will look to adult education and training as a way to help unemployed adults find their way back into work. The bad, if not unsurprising, news is that in recent years, adult education and training has been both on a decline and focused on the ‘already-haves’. Excluding apprenticeships, adult study across further and higher education has declined by about 20 per cent since the early 2000s.

Moreover, both in-work and out-of-work training has been gone disproportionately to adults with higher-level qualifications: figures from Understanding Society, a longitudinal survey, show that while more than one-in-three (35 per cent) of 25-59-year-old graduates report having had any form of training or education outside of full-time study, only about one-in-five 25-59-year-olds with GCSE-equivalent or lower qualifications report the same.

Our research finds that there is a strong association between training and returning to work, particularly among non-graduates

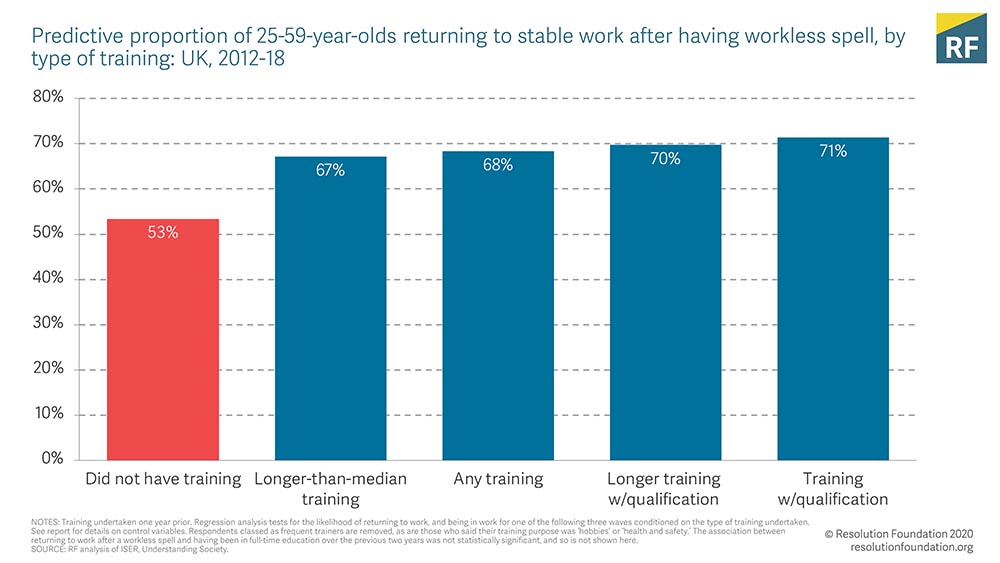

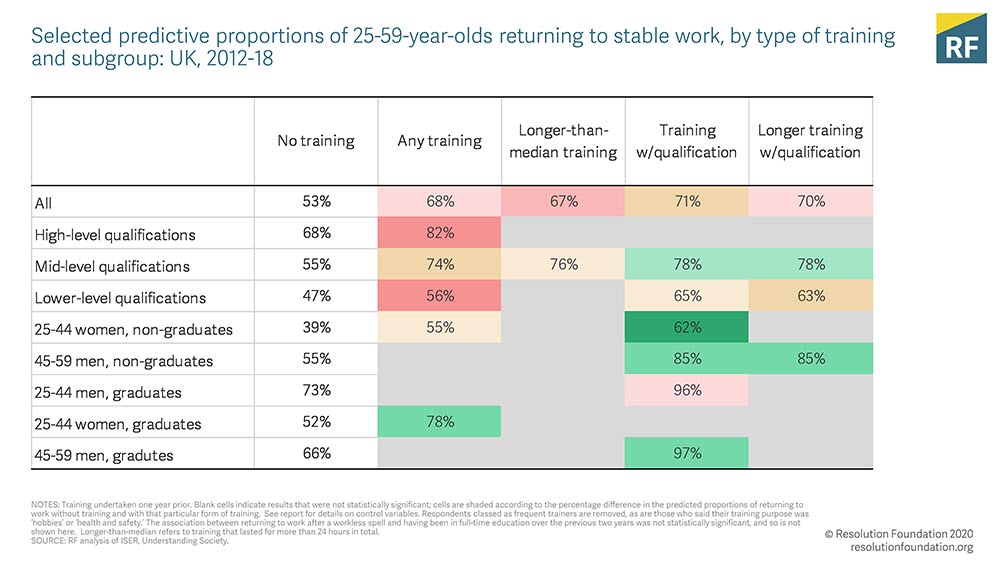

The good news is that our research, which uses Understanding Society data from 2012-18 to track adults’ career transitions, finds that even after controlling for several personal and work-related factors, education and training can make a substantive difference to the odds of a person who has moved out of work being able to move back into it.

For instance, absent any education or training, we would expect 53 per cent of 25-59-year-olds who had recently moved out of work to return to a job within two years. By contrast, we would expect 71 per cent of 25-59-year-olds who had training that resulted in a qualification to do so (a difference of 19 percentage points).

In fact, our research shows policy makers that they can have an even greater effect by marshalling education and training efforts to out-of-work non-graduates, and in particular younger non-graduate women.

Without any training, we would expect 39 per cent of 25-44-year-old non-graduate women who had recently moved out of work to return with two years, as compared against 62 per cent of those who had undertaken training resulting in a qualification (a 23 percentage point difference).

But beyond returning to work, there is the question of how to help workers in struggling sectors change tack

Beyond returning to work, many adults will want – or need – to change the sector in which they work, and ideally change sector while obtaining higher levels of pay than they received before.

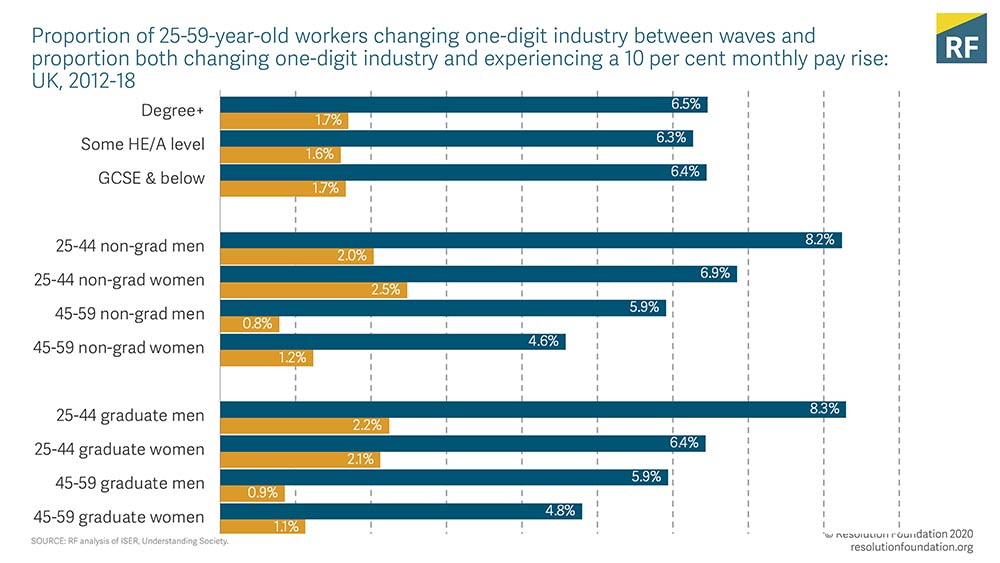

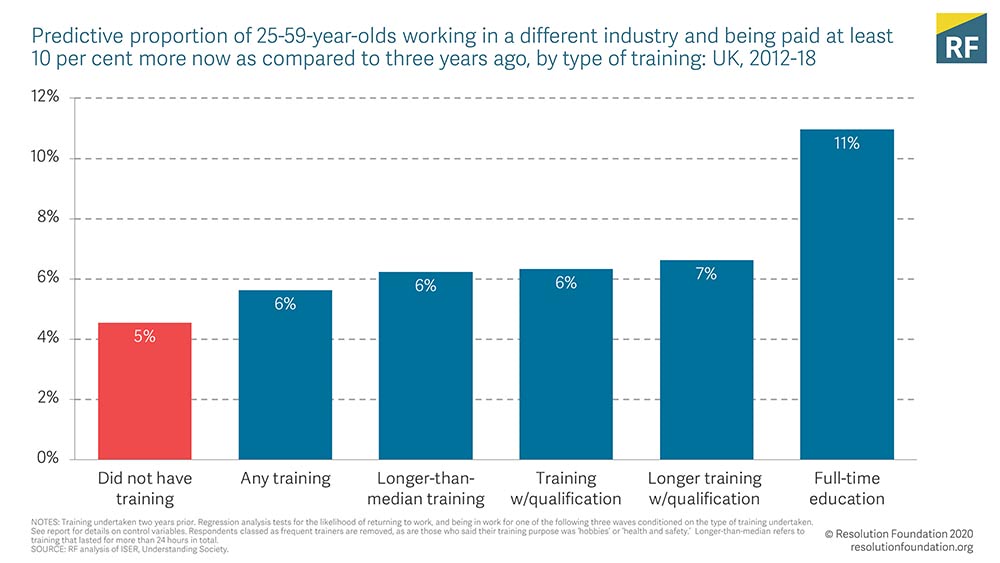

This is a more difficult prospect: our research finds that while about six per cent of adults change the industry they work in from year to year, only two per cent manage to change industry and obtain a substantial (minimum 10 per cent) boost in monthly pay.

Our research finds somewhat small, though statistically significant, associations between most forms of training and changing industry, as well as between most forms of training and changing industry while obtaining a minimum 10 per cent pay boost.

The clear exception to this is full-time education, wherein we found a more substantial effect. While we would expect just 5 per cent of workers who have not experienced training to have both changed industry and received a minimum 10 per pay rise compared to three years ago, our findings indicate that 11 per cent of those who had completed some full-time education in the interim would have done so. These effects are, again, largest for non-graduates, particularly older non-graduate men and women.

We shouldn’t infer from these findings that short or part-time courses are unlikely help a person change their career. Instead, these findings seem to cast a light on the difficulty of doing so. While there are a host of likely culprits, it’s worth considering the difficulty of deciding whether and how to move: for instance, understanding how a person’s skills translate into a new field, how they should set about finding a new role, and whether that move will financially pay off. And even if a person has identified the type of industry and role they’d like to move into, there’s the question of training for it: can they afford to balance study, their current job and family responsibilities – let alone the trepidation that can often come with re-entering the classroom after a long time away.

Policymakers should focus their current efforts on tackling unemployment, while also considering the role of job creation and broader post-18 reforms

So, what does this all mean for the current crisis? First, policy makers should of course look to education and training as one way to tackle the high levels of unemployment that we are likely to be facing. Even though helping recently-redundant workers to re-enter the job market could prove far more difficult when vacancies in labour-intensive sectors like hospitality and retail have fallen, there is strong evidence to suggest that training can play a substantial role in helping lower-qualified workers re-enter a job after a spell of worklessness. It’s right that these opportunities are marshalled towards those who will need it most.

Where the goal is to shift large numbers of workers from one sector to another, our findings are more challenging. In the short-to-medium term, government should consider policies that would help adults re-enter work and/or change career by adopting more sector-focused job creation initiatives that have training built into them. For instance, we at Resolution Foundation have previously called for investment in social care and ‘green jobs’ like home retrofitting as a way to boost sectoral reallocation and tackle unemployment during this crisis.

Running alongside of this, policy makers are right to consider ways to help adults retrain over the longer-term. This could include for instance, proposals to allow adults access maintenance support while studying in further education, in addition to proposals from Review of Post-18 Education and Funding (the ‘Augar Review’), like allowing adults to access finance for other levels of courses on a modular basis and build up credits over time and removing ‘equivalent or lower qualification’ restrictions (which bar students from studying a course that is at the same or lower-level qualification, even if it in an entirely different subject). As ever, no single policy will form a panacea for out-of-work adults and those in need of a new start – time to get to work.

Kathleen Henehan, Research and Policy Analyst, the Resolution Foundation

Responses