Methodology Across the Millennia

In his handwritten yet entirely legible sixteen-page reading for students, Peter Checkland (1) explains how, by the 1970s, the subject systems thinking had evolved into two complementary streams. Still dominant today, the goal-seeking ‘hard’ style strives to find the best way to achieve agreed objectives – as when Ford designs and builds a more efficient engine, or some team of distribution specialists devise a more economic route to transfer materials. Not so well-known, the ‘soft’ style tackles a hazier class of problems, social and political, where organisational personnel admit nagging doubts about how to define their issues. Leading early practitioners of soft systems mentioned via Checkland’s handout are Professors Russ Ackoff (University of Pennsylvania), Professor Charles West Churchman (University of California), and Stafford Beer (an independent consultant).

Lancaster University’s scholar Checkland assessed his fellow researchers and found their ideas to be inadequate for investigating our ever-changing social world; rich in variety and hard to predict, society endures yet changes through time. Responding politely to fellow researchers in this novel field – one unsuited to traditional teaching programmes – he asked how their preferred modes of systems thinking will help achieve and maintain desired human relationships when they focus strongly on design. These authors, Checkland warned, fail to provide adequate guidance on how to achieve objectives or action decisions among participants voicing ‘incompatible interests.’ In the case of Beer, why is a natural system like the brain an appropriate model for discussing human organisations? Brains in general rather than one in particular? Checkland argues that traditional practice by clerks, accountants and other personnel persist alongside a unique culture of local myths and power struggles. Yes, there’s a college in this precinct, but which underlying issues stir important discussion and even anguish among staff and students?

Taking organisations (and their frequently taken-for-granted use of language) to be problematic settings, Lancaster’s approach Soft Systems Methodology helps arrange the interpretation of organisational life by those who work within them. Consultants should provide only an advisory role. SSM does not present complex human institutions with a blueprint, but instead hands over low-tech principles to support serious enquiry. By low-tech, I mean A3 flipcharts and felt tip pens: a pair of aids that have proved invaluable to date, supplemented by whatever additional gadgets the folk involved want to bring onboard. Taking on an external consultancy role, post-graduate teaching role, and the role of course designer at Lancaster, Checkland proposed a methodology that changed through time; the most recent outline has four recursive stages:

1 Appreciate the complex organisational setting;

2 Devise systems models hopefully relevant to

improving how things get done;

3 Conduct debate via the models;

4 Implement any change agreed in stage 3.

Folk taking part in an enquiry can traverse this loop of four stages as often as they wish. SSM is neutral as regards human hopes, patience, and values. What might count as ‘an improved mission’ for a San Franciscan chapter of Hell’s Angels? Even leather-clad bikers are beholden to some kind of politics. Will the boss laugh at a suggestion and slap shoulders – or reward his outspoken deputy biker with a punch? Methodology merely brings structure to enquiry, an adaptable approach for trying to establish relevant views in opaque circumstances. That is, relevant models may well emerge during the course of an enquiry, but much depends on participation by organisational members: their ideas should steer the enquiry, acknowledging the constraints of local politics.

Models shared in SSM should be distinguished from the type of mathematical models recently deployed in Covid research (2) to predict peaks per year as well as their amplitude from year to year, each shape being related to vaccinations, previous infections, and the weather. Never ambitious representations of how part of the world actually ‘is’, even less what it will become, Checklandian models are only conjectures to stir learning and change through coherent parley. As a rational arrangement of phrases, each abstract system could in principle be put into action by those taking part. While textbook guidelines (3) have assisted the construction of soft models in live case studies, the methodology per se is neutral regarding mission, time, and culture. BBC production teams might agree to adopt SSM for a couple of months, as could a modern-day mafia family. Or priests, working near their monastery one thousand years ago.

In The Year 1000 (4) investigative journalists Lacey and Danziger present a remarkable glimpse at England near the turn of the first millennium. From January to December, each of twelve chapters opens with an illustration borrowed the Julius Works calendar. This era was a period when the country’s modest population of one million was healthier than their Victorian descendants, though with medieval life often proving short, simple, and quiet, at best disturbed only by the noise of wooden cogs turning in a watermill, or the bell of a church tower. Like us, folk had human worries over receding hair, fatigue, profits, and wicked double-entendres. For those choosing an ecclesiastical life rather than trade or the administration of justice, England’s monasteries offered a structured week of silent prayer and responsibilities, some conducted outside the monastery grounds.

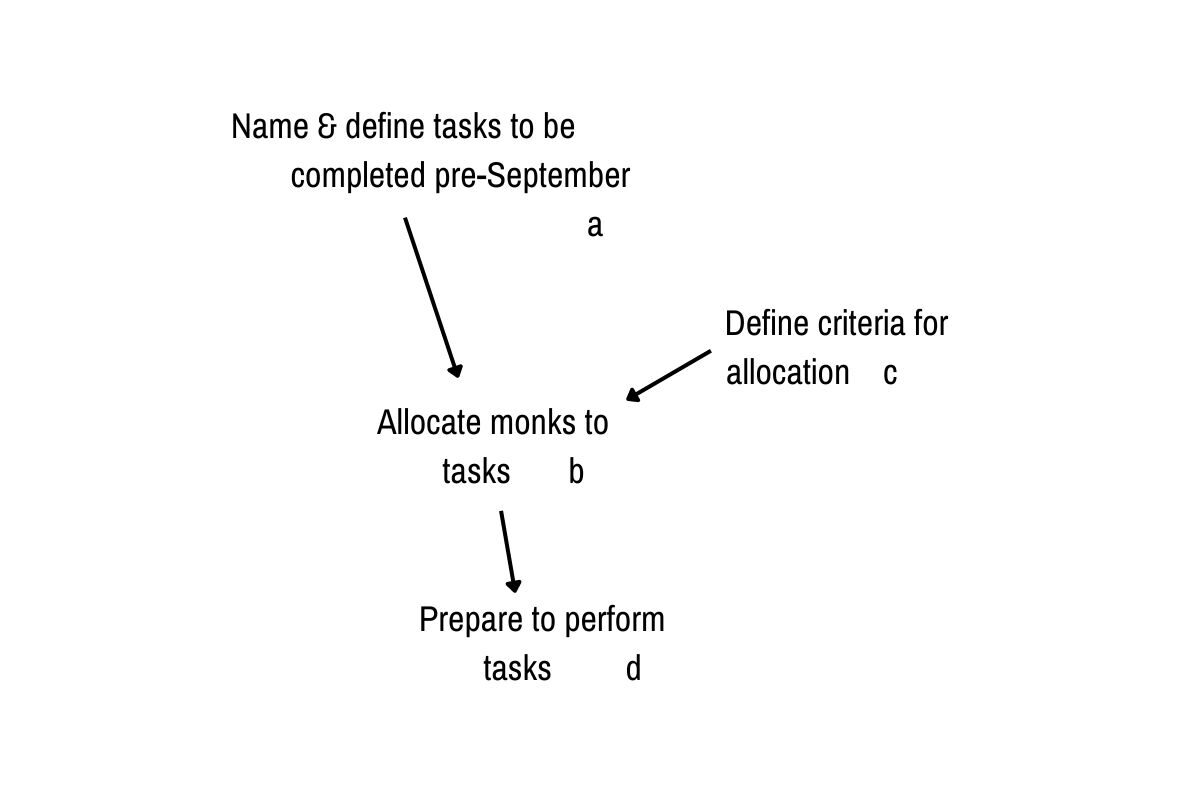

A new bishop decides to give a group of his cathedral monks additional tasks, to be completed by the end of August. Already busy, they become anxious – exactly how should this be done? A senior figure draws up a systems model representing the assignment of tasks to aid debate, explaining the sketch does not spell out ‘how’ but might direct parley in a useful direction. And, he explains, talking about the model is a jolly good way to assess its relevance!

A sample of the model’s activities are shown here for illustration:

Sharing such a diagram (usually done freehand, hence Wordless) gives people a focus for reflection and discussion. The presenter should ask, with modesty, does my diagram help explore our hazy scenario? Are notional activities a, b, c, and d being done in ways which are effective, or are participants rushing into action too soon? For instance, does activity c take into account monks’ health, skills, and usual responsibilities within the months July and August? Activity d may encourage remarks on assistance from technology. Has it been discussed?

As an explicit means to question opinion, each model facilitates discussion a day or two after tasks commence in this (admittedly hypothetical) application of SSM. The use of arrows can be questioned too. Although the arrow linking a and b implies information being transferred, has this been done well? Or did an inattentive human messenger deliver a poorly understood version of what had been told to him the previous day? In Lancaster’s more complex studies, diagrams (3) appear to borrow modern corporate parlance, such as a model’s phrases ‘Obtain and appreciate development plans’ and ‘Relate plans to corporate objectives and the Networked Product Line’. This wording looked appropriate within the high-tech culture of International Computers Limited, yet the underlying aim of SSM remains the same across society: it enables purposeful relationships to be consciously explored by a rigorous abstract language. People taking part learn their way to an adequate social arrangement, just as the Middle Ages apparently began a probing and sceptical spirit which slowly altered ‘the unquestioning nature of medieval thought.’

By Neil Richardson

- Soft Systems Approaches, Some notes and bibliography, P B Checkland 1983

- Five-Year Forecast, i news, March 3, 2023

- Soft Systems Methodology in Action, Chapter 6, P Checkland & J Scholes 1998

4 The Year 1000, R Lacey & D Danziger 1999

Responses