What can Sir Michael Barber’s review accomplish for FE? Asks Professor Tom Bewick

Sir Michael Barber is an educationalist whose own academic background and career reflects those of other recent ‘skills advisers’ to occupy the space: Baroness Wolf, Lord Sainsbury and Sir Philip Augar.

Barber went to an independent fee paying school followed by Oxbridge, as is typical of many, although not all, of the external advisers appointed by government.

Why no advisers who have actually worked in FE?

To many who have spent a lifetime working in further education, it is more than a little odd that the choice of people to review the post-16 skills and vocational system over the years have (more often than not), originated from a background, with little or no personal experience of the state education sector.

State schools were not necessarily where these advisers were taught themselves; and it is very unlikely they have sent their own children to an FE college or enrolled them in a formal apprenticeship. Yet still, these are the people government regularly ask to pontificate about skills and FE.

As a diverse nation, if we are really committed to equity and inclusion, then this situation has to change. Ministers need to start appointing more advisers from demonstrably working-class backgrounds. As a minimum, we should expect to see more people elevated to these important positions with more direct experience of the state education sector in future.

Of course, we need people appointed on merit. And all of these advisers have impactful CVs.

But let’s not fool ourselves that elites have rather a regular habit in Whitehall of recruiting fellow elites. Research by the Sutton Trust makes this point: 59 per cent of perm secs were educated at fee paying private schools in 2019 (compared to 7% in the general population as a whole); while 56 per cent of these most senior civil servants attended just two universities – Oxford and Cambridge.

The current perm sec at the Department for Education is also a product of the same privileged system, with links to the aristocracy.

In other fields, it is usually the case that someone with a considerable track record in a profession would be asked to review their own sector. It’s known as independent peer review. In FE, peer review refers to someone who is an unelected member of the House of Lords.

For example, senior judges are often appointed to review an aspect of their own legal profession. We’ve seen celebrated cardiologists and surgeons asked by the Department of Health, to lead reviews of patient services for those struggling with long-term conditions.

Vice-chancellors have led various higher education reviews over the years.

It’s a sign perhaps of how little trust or respect the FE sector has managed to secure in the eyes of senior decision-makers in government, over the decades, that ministers call upon very accomplished – but nevertheless complete outsiders – to provide insights into a world that they themselves have very little experience of.

What can this latest review accomplish?

Sir Michael’s latest book is called Accomplishment: How to achieve ambitious and challenging things.

It reads a bit like the sequel to his earlier 2015 book: How to run a government so that citizens benefit and taxpayers don’t go crazy.

In being appointed by government to lead what will amount to the fifth skills review in 12 years, you sense he may need to draw on all his experience as the proclaimed ‘overlord’ of public service delivery.

It is what another former Downing Street adviser, during the New Labour years, Patrick Diamond, refers to as Barber’s more ‘sober, technocratic delivery mantra’. This stands in stark contrast to the more erratic behaviour, or ‘hard rain’ philosophy, of Dominic Cummings, when he was advising Boris Johnson.

For Diamond, now associate professor of public policy at Queen Mary University, Sir Michael represents an outdated approach of policy change that is built on ‘machine systems’ thinking.

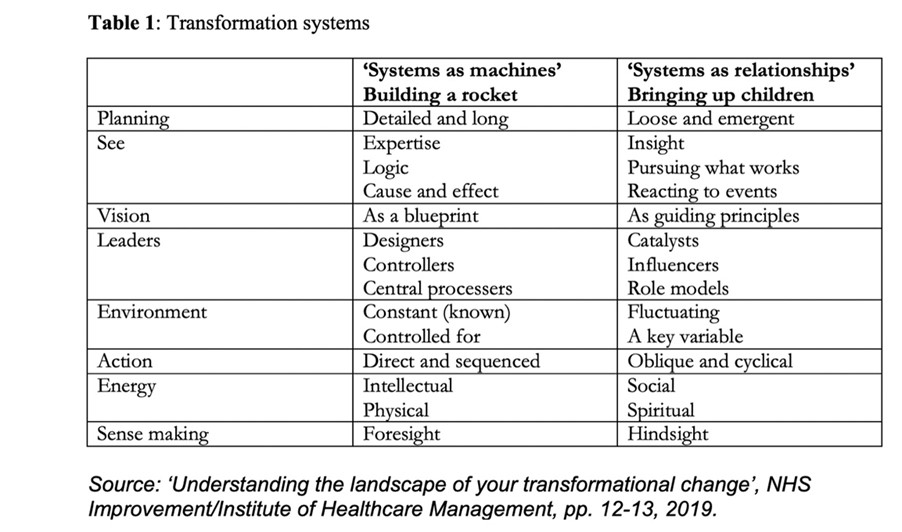

For example, Professor Diamond points to the contrast between building a rocket and bringing up children.

In the former, it is necessary to deploy a precise scientific method. Building a rocket, including the delivery systems to get astronauts safely into orbit, requires experts who can unquestionably follow management directives and compute precise measurements. There is no margin for error, since this could be catastrophic for any crew going into space.

However, in bringing up children, what really matters most – according to the Institute of Healthcare Management – is the quality of relationships and the presence of trust. Table 1 helps explain further the differences in approach.

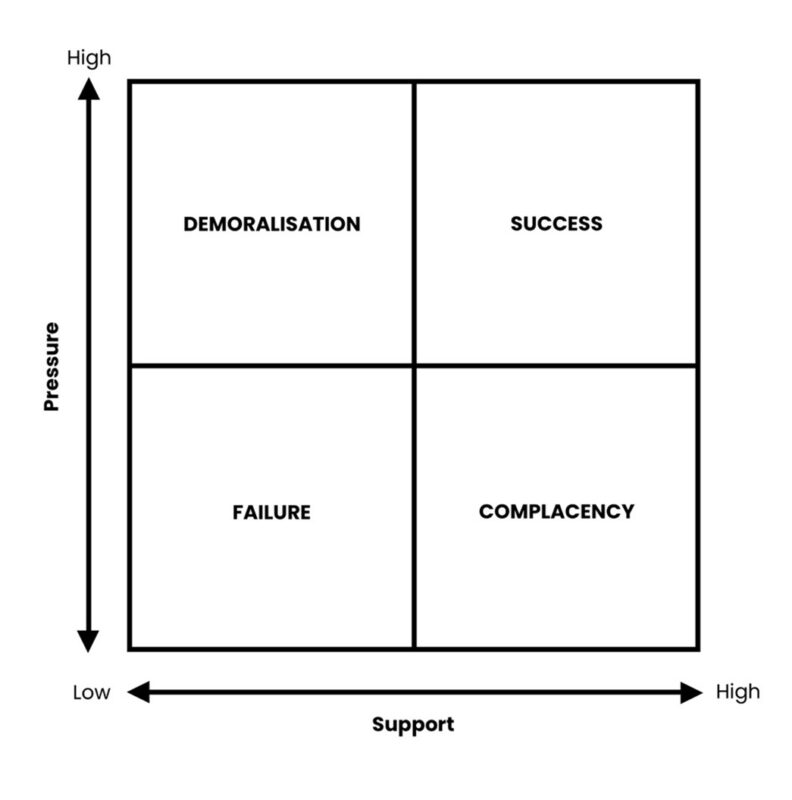

We see evidence of Barber’s ‘machine systems thinking’ in his latest book (Figure 2). For him:

- ‘Whatever the goal, never fail to establish a functioning delivery chain with a combination of pressure and support at each level.

- Think through the relationship between the links.

- No delivery chain, no delivery.’

As adviser to education secretary, David Blunkett and prime minister, Tony Blair, Barber explains that one of his key challenges was to understand how, based in Whitehall, he could effect change in the reading methods of teachers and pupils’ performance dispersed across more than 16,000 primary schools.

From the perspective of a young female learner, he asked the question: ‘What can I, sitting in Whitehall, do to ensure that she and many thousands like her learn to read and write well over those years? The answer is ‘nothing’… unless we construct an effective delivery chain (p. 85).

It is this ‘delivery chain’ model that puts Barber firmly in the policy science tradition of what Lindblom once wrote about as ‘top-down rational analysis’.

In this model, public administration is a hierarchy that usually starts with a political target.

In 1997, less than two thirds of 11 year olds on average reached the expected standard in literacy. The Blair government wanted to increase the number to at least 80 per cent of the cohort.

Barber’s top-down methods got results.

Following the introduction of the famous primary school ‘literacy hour’, the reading target was reached in 2004. And to this day, under successive governments, reading and writing standards have continued to improve.

England was ranked in 8th place, globally, during the latest Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS), conducted in 2018. The most up to date study is currently being undertaken, delayed because of the pandemic.

Figure 2: Combining Pressure and Support (in public services)

Skills systems as an ecosystem

It remains to be seen which model of ‘systems thinking’ Barber deploys in this latest skills review.

I’m convinced that if he tries to adopt a simple hierarchical top-down delivery chain model, like the literacy hour, it will fail.

But then that is perhaps not unsurprising coming from someone like me who believes that you get the best out of people and organisations by building ‘high-trust, high performance’ models of delivery, centred on a clear articulation of desired outcomes, instead of bureaucratic inputs.

Unlike state primary schools, the post-16 skills system is far more complex. Not least because getting world-class results out of a skills ecosystem is somewhere between building a rocket and bringing up children.

Indeed, the whole notion of ecosystems and policy complexity is really gaining ground in our modern understanding of the science of public service delivery. It is an approach the Dutch inspirational speaker, Alexander Den Heijer, captures beautifully, explaining:

‘When a flower doesn’t bloom you fix the environment in which it grows, not the flower.’

In other words, we need a critical look at the skills system across the UK that doesn’t just analyse it from the perspective of a set of Whitehall programmes run by a collection of quangos.

After all, what is the point of skills boot camps, T levels and higher technical qualifications if they fail to contribute to increases in workplace productivity and therefore better living standards for everyone? Unless these government owned schemes can be demonstrably proven to support economic growth and human flourishing, they amount to little more than taxpayer funded displacement activity.

The existence of these initiatives cannot just be an article of faith, either, presented by departmental press releases as the new ‘gold standard’ or ‘world-class’, when very few objective metrics currently exist to actually verify if such claims are true.

Instead, we need to think about what might be going wrong from the point of view of the behaviours amongst a complex array of different policy and delivery actors; as well as ask more critically, the following sorts of questions:

Is the environment in which the state, employers, communities, educators and learners operate really the best one to deliver a genuinely world-beating post-16 education system?

Are we basing our policies on a clear long-term vision and a set of shared values, that with the right mix of incentives, rewards and penalties, will help build trust and accountability, preventing things from going in the wrong direction?

Is it absolutely clear who is accountable for cultivating or delivering any particular part of the skills ecosystem?

And crucially, how do we know what success looks like for the whole of the country, when we add up all these individual (policy) parts?

At the moment , it is not clear whether we have answers to any of these questions.

To be fair, Barber himself recognises this sort of challenge in his own writings:

‘… it is never a simple choice between central control and devolution, between top-down and bottom-up; it always a question of establishing the right combination between the two.’ (p.90), he says.

As we embark upon yet another potentially naval gazing exercise, the commissioning of this government review ought to provide good enough reason for the FE sector to get properly engaged in the debate.

The alternative would be for us to be passive, allowing Barber’s work simply to become yet another Whitehall driven technocratic tick-box exercise.

Sector colleagues should fully engage by talking and writing about what they would like to see.

Because we really do have to learn the lessons and get it right. The future productivity and prosperity of our country depends on it.

Tom Bewick is the chief executive of the Federation of Awarding Bodies and Visiting Professor of Skills and Workforce Policy at Staffordshire University. He is also the presenter of the Skills World Live Radio Show, broadcast by FE News.

Responses