The importance of second chances in our education system

Across the country, there are millions of adults with poor qualifications and low levels of skills. In fact, a quarter of working-age adults in England are not qualified up to upper-secondary level (A Level or equivalent), which is above the OECD average and over twice the level seen in Germany and the US.

Recently, we at the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) published a landmark study on education inequalities, in which we argued that one of the fundamental shortcomings of our education system is the lack of adequate second chances offered to adults.

Not only do the low skills of millions of adults hamper national productivity, they also limit individual’s labour market prospects. By the age of 40, the average UK employee qualified to GCSE level or below earns half as much as someone with a degree.

Therefore, if we are serious about tackling inequalities and boosting the productivity of the wider economy, it is essential that we ensure that the education system provides all adults with the education and training opportunities they need to prosper.

Those who don’t do well in their GCSEs don’t tend to catch up

In last month’s GCSE results, nearly a quarter of 16-year-olds did not achieve at least a grade 4 in GCSE English. In maths, more than one in three pupils failed to meet this benchmark.

These pupils will be required to retake their English and maths exams, but many will not pass the next time around: less than 30% of GCSE English and just 20% of GCSE maths retakes were passed this year.

More broadly, nearly half of pupils who have not achieved at least five good GCSEs or equivalent by age 16 still have not obtained them by the age of 19. Even looking a decade out from their GCSEs, around 30% of people who missed out on GCSEs the first time around had not earned these qualifications by their mid-20s.

This educational stasis results in a high share of young adults without basic skills, which can severely limit their life chances.

The decline of educational opportunities for adult learners

As well as the lack of progress among young learners, over the last decade there has been a significant decline in the number of adults taking qualifications which can address existing skills gaps.

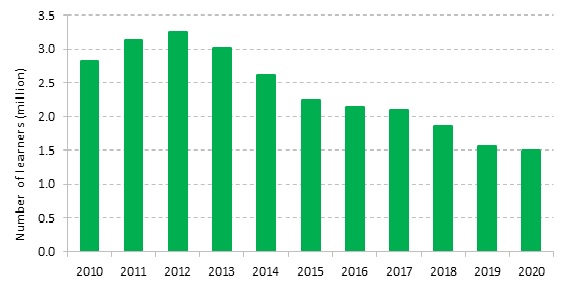

In Figure 1 we show the number of adults taking classroom-based qualifications (i.e. non-apprenticeship qualifications) at Level 3 or below. Between 2010–11 and 2020–21, the number of adults taking low-level qualifications fell from around 2.8 million in 2010 to around 1.5 million in 2020 – a decline of roughly 47%

Figure 1-Total number of adult learners starting classroom-based qualifications at Level 3 or below in England between 2010–11 and 2020–21

For adults with low levels of education, these trends have made it more difficult to access opportunities to upskill through formal education, which means that existing educational gaps among adults may not be closed and may even be widening.

Funding restrictions inhibit access to post-16 education

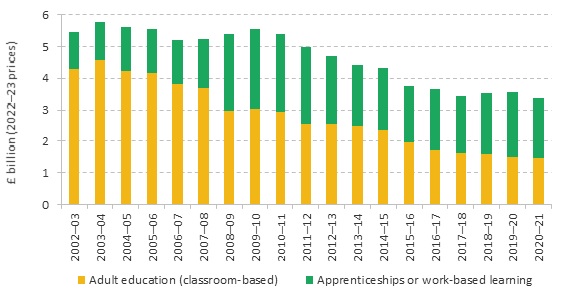

Policy plays a key role in limiting educational opportunities. Over the last decade the government has restricted the amount of funding available for adult education. In Figure 2, we show the level of public spending on adult education and apprenticeships.

Figure 2-Total public spending on adult education and apprenticeships

In 2019-20, spending on adult education was nearly two-thirds lower in real terms than in 2003–04 and about 50% lower than in 2009–10. The decline was mainly driven by the removal of public funding from low-level classroom-based courses.

Although some of these courses had been found to have low returns for learners, cutting back on them has made it more difficult for adults with few existing qualifications to access opportunities to reskill.

The policy response to issues with post-16 education

The problems with post-16 education that we have highlighted so far aren’t unfamiliar. Indeed, the government has introduced a number of reforms in recent years in an attempt to ameliorate these issues, but it is unclear whether they go far enough.

In recent times, the government has set out significant additional funding for adult education, including the £2.5 billion National Skills Fund. This money is being used to restore the entitlement to free Level 3 courses for adults and also to fund new training programmes, such as skills bootcamps and the Multiply programme.

In general, providing effective support and training for adults is a significant challenge. While new programmes like Multiply are likely to help those who left schools without good GCSEs or equivalent qualifications, they are relatively untested and are unlikely to lead to formal qualifications.

In addition, the government’s extra spending on adult education must be put into context. In a report published earlier this year, we found that the additional skills spending will only partially reverse previous cuts. Even with the additional money, total public spending on adult education and apprenticeships will be 25% lower in 2024–25 than it was in 2010–11.

Providing effective support and training for all adults is critical. Currently those who don’t do well at school are often left behind. A number of positive reforms have been made in recent times to adult education, but given the significant cuts to funding in the previous decade it is unclear whether this will be enough to provide everyone with the second chances they need.

By Imran Tahir- a research economist at the Institute for Fiscal Studies and an author of the ‘Education inequalities’ chapter of the IFS Deaton Review

Responses