Where will all the skilled workers come from?

A labour market crisis

The UK has lots and lots (and lots) of jobs, but not enough people with the right skills to fill them. Or wanting to.

According to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), we recently posted over 1.3 million vacancies, after recovering from a low of 343,000 during Covid19 1. Across large swathes of the economy, employers large and small are crying out for skilled candidates. But we now have less than one active job seeker per vacancy 2. This is putting pressure on wages, but wages are still failing to keep pace with inflation and the resultant cost-of-living crisis. Furthermore, if large enough numbers of suitable candidates aren’t there, then even quarterly 6.8% pay rises (including bonuses) won’t have the required impact on recruitment 3.

An international comparison

Reading a BBC article last week: ‘Dutch idea backfires’ it seems that we’re not alone. It describes how the social affairs minister recently came under fire for asking whether young workless people in the deprived banlieues of France could be attracted to fill vacancies in the Netherlands. In the face of a public backlash, Ms van Gennip felt compelled to re affirm her priority to help the million Dutch people who are out of work, as well as part-time workers, and that (the Netherlands) already has 800,000 migrant workers who should be treated more decently 4.

Have skilled workers ‘disappeared’?

In the UK, while the government is proud to parade a ‘historically high’ employment rate of 76%, we should scrutinise this figure more carefully. As Tony Wilson of the Institute for Employment Studies (IES) points out, in our country: “there’s still a million people missing from the labour force compared to pre-pandemic trends” 5.

As well as looking to people who are ‘unemployed’ to meet skilled labour demand, we need to remember that hundreds of thousands are currently labelled (and widely dismissed) as being ‘economically inactive’. There may be a variety of reasons for this. The majority have health or disability challenges, many are young men who lack work experience, and increasingly more are people aged over 50, including those struggling to find a renewed sense of purpose in later life. Female workers are generally doing much better than ever before. But overall, this still isn’t enough to make the whole country function and flourish again.

Looking again at the Dutch minister’s initial way of thinking, and considering Brexit, it turns out (according to the University of Oxford’s Migration Observatory) that it wasn’t until 2020 6. that net migration into the UK from the EU entered negative figures, four years after the vote. The FT also reports an offset of fewer EU migrants, by an increase (by 9%) in incoming workers from non-EU countries 7.

Most substantially however, many potential skilled workers are simply not visible in the unemployment statistics. They are ‘hidden’, which puts them on the fringe of the main radar of the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and consigns them to being an afterthought for politically focused policy makers. They are also very easy for politicians to ignore. But they aren’t just statistics, they are real people who should be provided with the employment related support and skills training that could make all the difference in their lives and boost the struggling labour market.

What is the real level of unemployment?

At the Institute of Employability Professional’s (IEP’s) annual summit in June, Professor Christina Beatty, from Sheffield Hallam University, highlighted just how many people are persistently ‘hidden’ from the headline unemployment figures:

Real level of unemployment by region, 2022

| Unemployment benefits claimants | Hidden unemployed on incapacity benefits | Real unemployment | % of working age people | Share of un- employment hidden on incapacity benefits | |

| Northeast | 74,100 | 54,000 | 128,000 | 7.7 | 42 |

| Wales | 67,400 | 83,000 | 150,000 | 7.7 | 55 |

| Northwest | 195,400 | 147,000 | 342,000 | 7.5 | 43 |

| Scotland | 122,300 | 102,000 | 224,000 | 6.4 | 46 |

| West Midlands | 174,600 | 61,000 | 235,000 | 6.4 | 26 |

| Yorks/ Humber | 141,400 | 78,000 | 219,000 | 6.4 | 36 |

| London | 299,200 | 72,000 | 371,000 | 6.1 | 19 |

| East Midlands | 97,300 | 49,000 | 146,000 | 4.9 | 34 |

| Southwest | 92,300 | 63,000 | 155,000 | 4.6 | 41 |

| East of England | 119,500 | 38,000 | 157,000 | 4.1 | 24 |

| Southeast | 170,000 | 41,000 | 211,000 | 3.8 | 19 |

| Great Britain | 1,550,000 | 790,000 | 2,340,000 | 5.8 | 34 |

There is a deep echo from as far back as the 1980s here, from when ex miners and others classed as ‘unemployed’ transferred to incapacity benefits en masse. While it was politically very convenient for the government to present a lower claimant rate as the prominent headline for public consumption, the truth was, that many did not move successfully and sustainably into skilled employment.

As a result, despite great strides having been made through world-leading employment and skills programmes, generational unemployment and economic inactivity hotspots have long persisted. This is partly what politicians are getting at when they repeat the ‘levelling up’ mantra. But there is still a very long way to go to reach the parts that governments of every type have so far been unable to trans formatively reach. What is more, the actual ‘hidden’ numbers of economically inactive people are much higher than even the table above shows. This is because some people aren’t claiming incapacity benefits (such as lone parents) and others aren’t claiming any benefits at all (such as young people living chaotic lives, sofa surfing, living with parents … and early retirees living from savings or other private provisions).

So, while it’s popular with the government to trumpet a historically low unemployment count (currently 1,584,200 [4%]), it is misleading to claim that “we’ve solved unemployment” (as a DWP Secretary of State notoriously did [in 2018]). In fact, even the baseline claimant count is starting to rise again, after a sustained period of steep decline 9.

Geographic disparities in employment and real unemployment

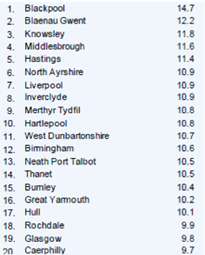

Professor Beatty also revealed the real level of unemployment as a percentage of the working age population across the country. In 2022 the 20 most affected districts below were practically the same as those recorded in her five previous (five-yearly) reports:

Professor Beatty concludes that we are now living in three “different Britains”

One of ‘Full Employment Britain’, covering 141 local authorities and 20 million people. In this Britain, average real unemployment is 2.8% and 14% of unemployment is ‘hidden’. This is the one we see most in the news headlines.

Another is of ‘Middling Britain’, covering 158 local authorities and 31 million people. Here, Britons experience an average real unemployment rate of 6%, and 34% of unemployment is ‘hidden’. This is a world less understood.

Then there is a third world (very seriously no pun intended) of ‘High Unemployment Britain’, involving 64 local authority areas and a population of 14 million people. Here, average real unemployment is 9.4% and 42% of unemployment is ‘hidden’. This is the social, economic and political reality that is most difficult to face.

Yet, there are millions of people concentrated mainly in former industrial towns and cities, coalfield areas, coastal towns and inner-city areas, who could be preparing to be the skilled workers that the country needs. Many face multiple and complex real and perceived disadvantages in the labour market, which hinder their motivation and impede their ability to prepare for skilled work. For many, the aftereffects of having contracted Coronavirus, and the more psychological phenomenon of pandemic-fatigue, are factors that don’t help at all. And neither do longer-term effects of economic inactivity on confidence, self-esteem, and mental health. Debt and housing problems can also create additional barriers to moving towards and into employment.

To add to all of this, we have started to hear about the ‘great resignation’; which describes a new trend for millions of people across the world to leave or change their jobs, instigated during the turbulence of the pandemic, which has created even more turmoil in the labour market.

European Social Fund (ESF) and UK Social Prosperity Fund (UKSPF)

The UKSPF (and bridging UK Community Renewal Fund [UKCRF]) is supposed to replace the 2014-2020 round of ESF, which (along with its managing authorities) has funded the kinds of employment related programmes designed to engage, train and support people who are further away from the labour market.

Unless much more is done to retarget this replacement funding, to fill the gap that ESF is leaving, then we will only see the dream of levelling up descend further into an unattainable nightmare.

But UKSPF commissioners do have the opportunity to learn from the current UKCRF pilots and introduce truly innovative programmes. By genuinely transforming how we apply best practice, we can make a localised, well-funded, well-delivered difference to the lives of millions of ‘hidden’, potential skilled workers.

Individual service accounts/ budgets

This transformative innovation would apply new technologies and delivery models systemically to employment related support services.It wouldn’t be unheard of to tailor and integrate relevant services, that have otherwise been commissioned in silos and disjointed in delivery. It has been achieved for people with disabilities and severe and multiple health conditions both by the NHS and through local authorities.

Coordinating services around the individual is the goal. Introducing personal service accounts would enable people to access help with their careers advice, employment support, skills training, health services, holistic needs and even housing requirements.

A capped budget would be available to jobseekers and economically inactive individuals whether they were claiming unemployment related benefits or not. Coordinated service sequencing would enable them to access multiple and aligned services in a way that is most effective for them in their locality. Having identified the employment, skills, health, equipment, travel, childcare or other holistic needs a coordinating professional would simultaneously source and apply for permission to purchase pre-approved services, while linking primarily into skills training (with funding separate but aligned) and third sector provision.

A similar approach was critical to the effective and widely celebrated ‘Circle of Support’ model, which was designed to help disabled jobseekers. It is also integral to the award winning ‘tech for good’ company, Beam, which is using crowd funding to pool funds into individual service accounts and helping homeless jobseekers to re-establish themselves in sustainable employment.

The ‘Circle of Support’ model was widely acclaimed by JCP and DWP. It assembles wide support into an individual’s needs-based engagement mechanism. This includes a dedicated Employability Professional, JCP Work Coaches, social services, housing officers, mental health support practitioners, debt management agencies, substance and alcohol abuse practitioners and the individual’s family members if requested. Teresa Scott OBE, said 11.:

“Over the last 20 years of running a wide portfolio of employment and vocational skills programmes, I have seen first-hand how integration within a customised and tailored intensive pathway, delivered by Employment Providers, is the key to success. Whether it be to address specialist employability needs, re-skilling, or sector-based pre-employment, the person benefits hugely from closing the loop around them. Providing a complete wrap-around service, personalised by an Employability Professional, which simultaneously addresses every individual barrier to work or skills need, drives both momentum and purpose within their job search. This ‘Circle of Support’ ultimately delivers a better service to the individual, along with value for money and job sustainability for the government”.

Coventry City Council has long modelled its own city-wide, multi-agency service according to an open-eligibility model with ‘no wrong door’ to access its services. But UKSPF could go even further still. Payments could be attributed to sets of defined pre-employment and in-work progressions, job entries, employment sustainment periods, training outcomes, learning aim achievements and in-work progressions. This approach also worked very well under the original DWP-managed ESF ‘Troubled Families’ programme, where a portfolio of defined progression outcomes triggered payments, along with payments for job outcomes and sustained job outcomes.

The integrated, collaborative delivery model is also similar to Greater Manchester’s Working Well model, which delivers services outside of the normal ‘siloed’ environment by pooling funding controlled by the combined authority. This has led to over 25,000 GM residents being referred to skills-based interventions from employability and health programmes (through devolved Adult Education Budget [AEB] funding). The combined authority can do this because they hold the respective budgets for employability, skills and health.

UKSPF is likely to be commissioned through devolved and local authorities as well. A similar approach could also work well on a national (albeit universally devolved level). Indeed, UKSPF is THE big opportunity for transformative change. This fund could be used to deliver services much more effectively via pooled personal budgets. Programmes would require maximum accessibility and eligibility, wherever individuals joined their multi-agency service, and whether they accessed it locally, on a devolved level, or through national commissioning.

The result would be that people claiming Universal Credit (or any other benefits, or no benefit at all) could access fully personalised support, funded via a Universal Framework, of Universally Funded Outcomes. The model isn’t unproven, but ‘universalising it’ would be a powerful innovation. It could bring the best of best practice together, simplify services for individuals, employers and providers, consolidate policy, funding, practice, and governance, and provide future facing opportunity for the powerful use of data and technology, in a much more secure, effective and sensible way.

Conclusion

The labour market crisis that we are experiencing is in part a complicated result of widespread, misaligned political, economic, organisational, and individual decisions. But if we can align these decisions, by aligning incentives, and provide opportunities and rewards for services succeeding, then we can create a tremendously powerful force for good.

By treating everyone “more decently”, including people who are currently ‘economically inactive’, we can find and train up many more skilled workers, and address the labour market crisis.

Notes

- Learning and Work Institute, ‘Labour Market Live’, 14 June 2022.

- Professor Christina Beatty, ONS; DWP, and Sheffield Hallam estimates, 8 June 2022

- Learning and Work Institute, ‘Labour Market Live’, 14 June 2022.

- Professor Christina Beatty, IEP Summit, 8 June 2022.

- Employment Response to Coronavirus; A Flexible Employment Programme for England & Wales (delivered regionally), Cosens Consult, June 2020.

Responses