How not to spoil your lunch

We English don’t have a lot of time or space for philosophy. We like to get on with things, not sit around pondering the meaning of life. When someone wants to persuade us physical things don’t exist we’re right there with Dr Johnson striking his foot with mighty force against a large stone until he rebounds from it, spitting out the words through clenched teeth, ‘I refute it thus!’

Much of the language we routinely use to talk about business implicitly yearns for physical activity rather than thought. We ‘nail it’, we ‘cut the mustard’, we ‘pick the low-hanging fruit’, or ‘kick the can down the street’. Even when we talk about thinking itself it’s as if we’d rather be using our feet than our brains: we’ll do it better by climbing ‘outside the box’, or at least by swapping the office for those elusive ‘blue skies’.

But in March 1994 I heard an FE principal tell the following story. He was, shall we say, towards the hard-bitten end of the spectrum and cherished a patriotic suspicion of abstract thought.

With due regard to my health and safety I’ll call him ‘Len’. He was meeting another principal for lunch who, to Len’s surprise, had brought someone along with him.

‘Who’s the company?’, asks Len.

‘Ah, this is Penny. She’s a philosopher, actually.’

Len takes a swivel at Penny looking as if he’d opened a tool box and found a frog.

‘She adds value to our work.’

Does she? says Len to himself thinking of the lunch bill. Cost, more like.

Anyway, the courses come and go, Len and his colleague chewing the fat about how things are and Penny staying shtum throughout but listening.

Listening aggressively, Len’s inclined to feel. So over coffee, he leans back and turns to her.

‘Well, you’ve listened to us for a good hour and more. What have you learned?’

‘I think’, says Penny, ‘that you believe your business is education but I wonder if that’s right? You both seem to me to be actually in the business of raising people’s self-esteem; education is merely how you’re doing it.’

Len feels as if he’s just been knocked out the way of a bus by a small child.

He takes a sip of his coffee.

Then another.

He suddenly has a lot to think about.

First, he expected Penny to respond to what had been said but she cut straight through the what to the why of the matter. That was perplexing.

Second, she was calling in question his career-long sense of purpose which was deeply unsettling and third, most worrying of all, she could be right. He felt immediately she was right. It was just that working all this out was a task and a half.

That was how Len and philosophy first collided. Granted, it wasn’t a comfortable experience but what if you’re reaching for the wrong fruit, kicking the wrong can or are in the wrong street? What if you’re better off thinking inside the box or contemplating grey skies? The consequences for you and your business could be a whole lot less comfortable still.

If you’re in Len’s position you can put this worry gently to rest by doing what he did: hire Penny. The rest of us have to manage by just doing our best to think like her as well as we can. So how was she thinking?

Penny probably didn’t understand a lot of the anecdote and detail in the conversation – who the people were, the colleges mentioned and so on. But she didn’t have to: it wasn’t relevant.

She was attending to what lay beneath the surface. She didn’t ask, what’s that? or, who’s that? but, why is that – or that person – important, apparently? Why are they talking about these things rather than others? What seems to be at the back of this conversation? What’s driving it?

Her first step was to listen out for what wasn’t said, yet was constantly spoken. That seemed to be about purpose, about the point of the two principals’ work. So she then asked, how clear do they seem to be about this? And she listened for that.

After a little while probably two ideas sprang to her mind simultaneously: a) it’s about means and ends; b) these guys are confused about it.

Final step, some more focused listening to see whether she could disentangle things herself.

This, or something like it, was how Penny arrived at the succinct statement that proved hard for Len to digest.

So in summary her thinking steps were:

- Identify the chief issue

- Identify what it comprises

- Straighten that out.

If Len and his colleague had sat down to this rather than lunch they might have come up with a couple of columns at step 2 that looked something like this table on the right:

The diagram now helps them to think about step 3 because there are some obvious questions begging in it:

- duplication for one,

- and should there be three goals or one in the Ends column?

- And if one only, which one?

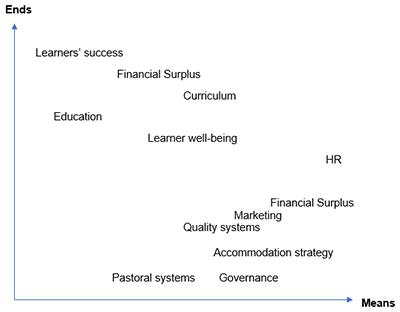

Alternatively, if they felt that thinking in columns was too binary, too black-and-white, they could have used a graph. If they had a large sheet of paper for the graph and smaller pieces for the ideas they could move these about to change the picture and deepen the discussion:

And the technique would work for any big idea. For example, if it was business priorities, not purpose, they could use columns or a graph split between ‘urgent’ and ‘important’.

And if the issue was multi-faceted that wouldn’t make it any more demanding intellectually; they’d just need a different kind of diagram.

A senior management team seeking consensus on stakeholder priority, for example, could share their views on how central or peripheral they judged the top ones to be using the diagram below.

You can easily see that results like these would probably generate some useful discussion:

|

|

|

|

As before the great advantage of using the diagrams is that they provoke such good questions: no philosopher needed.

All the SMT require is sufficient emotional intelligence to want to understand the reasons for one another’s answers. From that a powerful consensus could easily grow.

Not that philosophers don’t have their place. And to be fair to Penny, Len did ask. On the other hand you have to feel for Len. He turned up to that lunch appointment reasonably enough anticipating the salmon not a seminar.

And if he were even to glance at this account of his meeting it would be enough to confirm there was nothing extraordinary about it, nothing he didn’t routinely do with his senior team anyway.

’Philosophy? That? Move over. Common English good sense, innit.’

Chris Thomson, Education Consultant and former sixth form college principal.

Responses