When you know you’re wrong, you’re right!

The best thing written about leadership pre-dates the Harvard Business Review. In fact it pre-dates Harvard, pre-dates the English language, even. It was written in what we now call Ancient Greek by Sophocles, an Ancient Geek. It’s a play called King Oedipus.

Oedipus is a heroic leader. The people of Thebes have been greatly troubled by a monster who devours everyone that cannot solve its riddle. Quite a problem.

‘What goes on four legs in the morning, two legs in the afternoon and three legs in the evening?’

‘Er……..’ Chomp, chomp.

But Oedipus saves the city – the corporate enterprise – by finding meaning, the meaning beneath the confusing surface data. ‘The answer is ‘humankind’’! This kills the monster. The city – or company, we might say – is saved and everyone moves into health and prosperity. Oedipus is elected king, who else? CEO, in leadership terms.

Regrettably, that’s about as good as it gets for Oedipus. Next thing, the people of Thebes start keeling over with plague. Cue the heroic leader. Oedipus is able and he knows it. Didn’t he see off that monster? Anyone else’s crisis is but a challenge to him and he can’t resist a challenge. He’ll single-handedly get to the heart of what’s wrong and by dint of pure, penetrating understanding save the enterprise all over again.

He starts interviewing anyone and everyone who might have some relevant info and piecing together the answers. Only the answers aren’t good. In fact they’re very bad. Really dire? Probably still understates it.

In modern parlance we could put it accurately but euphemistically this way. Turns out, the corporate enterprise of Thebes isn’t afflicted with plague but is suffering from ‘lack of discretionary effort’ stemming back to Oedipus’ defective ‘emotional intelligence’. Only….

Did I say emotional intelligence? Actually, Oedipus has unknowingly murdered his own father. And Oedipus’s wife? Er, she’s his mum (also unknowingly). I stress the unknowingly bit. Not that it helps Oedipus. He takes the brooch from his tunic, stabs out his eyes, kind of one for each parent, and stumbles out of Thebes never to return. Ouch.

So what’s the leadership learning, then? At least two things.

Obvious one first: something about the limits of heroic leadership.

One astonishing success may not indicate an unfailing capacity to succeed.

Being the brainiest on the team doesn’t necessarily make you the best one to lead it. Especially if you’re so full of your own brilliance (hubris in Ancient Geek leadership jargon) that you never stop to consider the implications of the Johari window, the humility that comes from pondering all that you don’t know even about yourself, never mind the world beyond. People can manage without genius in their CEO but professionally they perish if their leader can’t supply the humbler qualities of clear direction and moral purpose.

The second point is much more optimistic. Credit to Oedipus for what he does right. He tackles the most important problem. OK, pretty unmistakeable but fair do’s, his judgement’s correct. He’s also right that it’s non-delegable: everyone needs to know the boss is on the case. And boy does he go for it. Totally full marks for the determination and single-mindedness he brings to the enquiry. The idea of failure simply never gets above his horizon.

But he teaches us something else too in startling clarity and it’s this:

Never be surprised if as CEO you set out to solve a problem which appears to be ‘out there’, rooted somewhere in the organisation maybe a very long way from your office only to find the more you learn about it the closer it seems to be creeping to your threshold…to your desk…to YOU.

When this happens, you get a pretty sinking feeling. If you’re not used to it, it’s perplexing, frustrating, you feel angry and it saps your confidence all at the same time. Not good.

The way out of it is first of all to recognise it’s not personal. What’s happening goes with the position not your personality. What you thought was malfunctioning ‘out there’ in the organisation is probably the result of policy or procedures not working, either because it’s badly framed or because it’s not being implemented correctly. As CEO, you’re responsible for the optimal functioning of policy, procedures AND people so of course the problem boomerangs back at you. If you’re feeling down about it, take heart: it’s a positive sign you’re living up to your job.

If it’s not an implementation problem, the chances are it’s because of all the small but significant signals staff have been interpreting from your behaviour as CEO. These can massively affect organisational culture and behaviour and not always for the best. In the words of Lou Reed, spitting in the wind comes back at you twice as hard. Even if you didn’t know you were.

Beyond this recognition is something even more important. If the problem is with you it’s yours to control. You may be able to rectify faults in policy or procedure quite quickly. If it’s people you can work with them bit by bit to improve things. Changing your own behaviour may mean swallowing some pride and may take time and some help to break old habits but it’s doable.

If you can get over the initial nasty shock when that boomerang catches you between the eyes, enormous benefits for the organisation can follow.

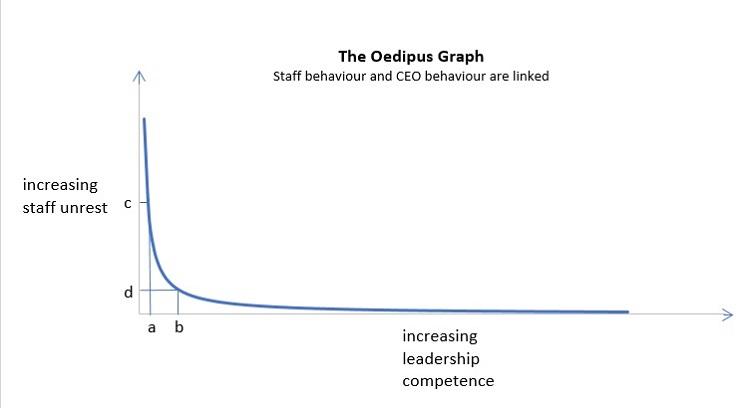

Here’s a graph that tries to show how. It’s not by Sophocles.

The first point is that not everyone will accept the reciprocity between CEO and staff behaviour. I remember taking the results of a staff survey to a governors’ meeting with some trepidation. ‘No more than I’d expect’, said a business governor, ‘that’s the way staff are’.

But if you accept that staff behaviour isn’t fixed and does relate to a CEO’s own behaviour then in some circumstances huge improvements can be achieved very quickly. Quite a small change in CEO behaviour – maybe what feels like a concession – represented by the shift from ‘a’ to ‘b’ on the graph can produce a really significant change in the way staff feel (the distance ‘c’ to ‘d’) with a consequent improvement for the organisation in terms of discretionary effort, staff being prepared to go the extra mile.

But the graph also suggests that after that initial big turn-round, you shouldn’t expect repeated large strides: the more leadership improves thereafter, the less impactful change is. It becomes more a question of small, incremental measures which contribute to maintaining a harmonious status quo.

I also like the way the graph is asymptotic – the lines never cross the x or y axes however far you extend them – indicating that however bad it can get, leadership is never entirely without hope and also that however brilliant it is there’ll always be some staff who’ll grumble about it.

And anyway, cheer up. There’s no monster in the foyer asking visitors impossible riddles, no one’s at their desk dying of plague and you haven’t……OMG, have you?!

Chris Thomson, Education Consultant and former sixth form college principal.

Find him on LinkedIn.

Responses