The Funding and Delivery of Adult Social Care in England

What is Adult Social Care?

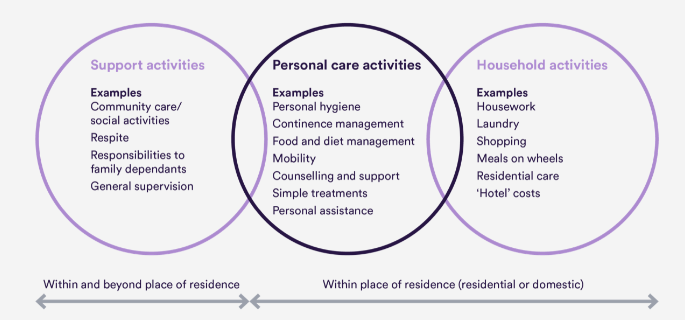

Social care supports adults of all ages, who might need help with activities or daily living because of age, disability or illness, to live independent and fulfilling lives.

This includes help with personal care, such as support with washing and toileting, but extends to a much wider array of activities such as day care and support to go on public transport or take part in hobbies (see Box 1 for selected examples of activities in social care).

Social care can be delivered in care homes, people’s own homes, supported housing or in the community.

Long-Term Care

Over 800,000 people in England were receiving long-term support paid for by the state in 2019-2020. There are no firm numbers about how many people pay for their own care but it is thought to be approximately half of all care users in England. Social care is generally more expensive for people paying for care themselves than it is for people funded by the taxpayer.

A Complex Funding and Delivery System

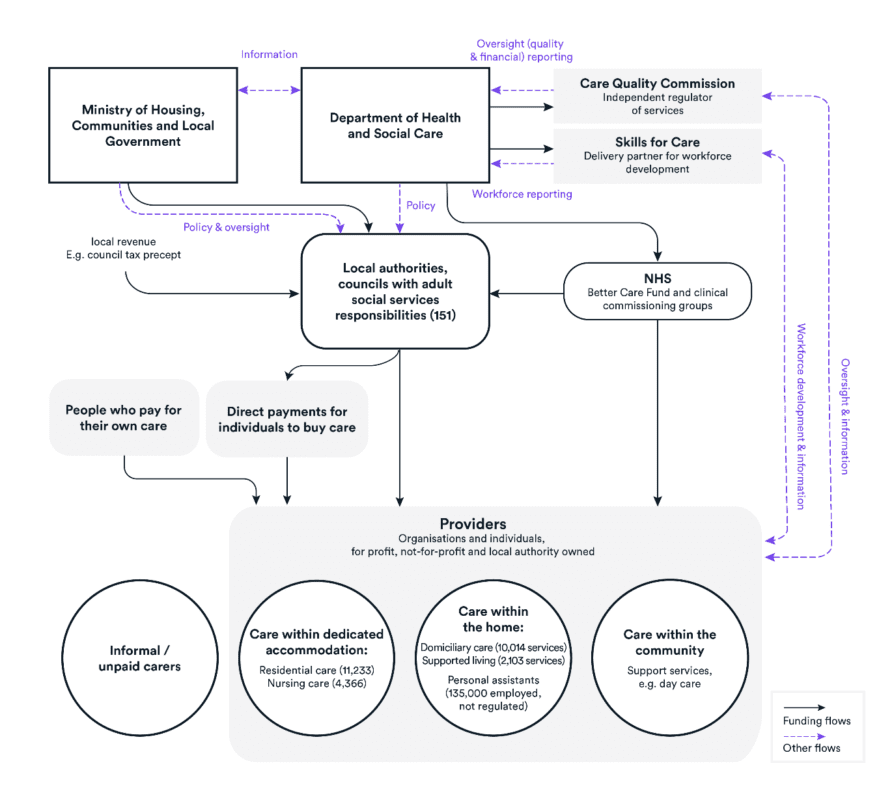

The funding and delivery of adult social care in England is complex (see Box 2). Funding comes from both national and local taxation. Delivery is the responsibility of 151 local authorities in England. Skills for Care is the delivery partner for workforce development, although the main post-16 education and skills budgets operated by the Department for Education also support workforce development.

Eligibility

Compared to the NHS, however, social care is not free at the point of use, which means many people have to pay for care and support themselves. Access to publicly-funded care is dependent on how severe your needs are and how much money you have. Everyone who feels they require social care can receive an assessment of their needs by their local council – this is called the ‘needs test’.

The Current Means Test

Those with needs above a certain threshold can receive funding for social care but only if they also pass a ‘means test’. A person’s means encompasses everything they own, including their income, assets (e.g. a person’s house), and their savings (e.g. a person’s ISA). Anyone with more than £23,250 must pay for all of their social care costs themselves.

Funding Sources in 2021/22

Local councils have the legal responsibility to organise social care for those who are unable to fund it themselves. It was projected that councils across England would spend around £18bn on social care prior to announcements in the Autumn Budget and Spending Review 2021. Councils receive funds for social care from three key sources.

Direct Central Government Funding to Local Authorities

In 2021/22, direct funding from the Treasury to all Local Authorities is estimated to be £9.1bn. This is intended for all council services, not just social care. Critically, central government funding has more than halved in the past ten years, meaning councils have much less to spend on social care and their other responsibilities.

Local Revenue Raising

Local authorities can raise funding through revenue raising through, for example, the Council Tax and business rates. Council Tax has been increasing in recent years and the amount it is able to raise varies across the country. Councils are also able to add 3% to Council Tax bills for the social care precept (money specifically for social care).

NHS

The NHS pays for some social care services for people deemed to require social care because of a health need (such as cancer).

Funding Announcements for 2022/23 Onwards

As part of the Autumn Budget and Spending Review 2021, the Government has confirmed additional funding from four main sources: (i) dividend taxes; (ii) Health and Social Care levy; (iii) Central Government Funding, and (iv) Council Tax and adult social care precept.

Dividend Taxes

The Autumn Budget and Spending Review 2021 confirmed an increase in income tax rates on dividends. This UK-wide tax increase is expected to raise £0.6bn per year, amounting to £1.8bn over three years.

UK Health and Social Care Levy

Building on the announcement made in September 2021, the government in the Autumn Budget and Spending Review confirmed the introduction of the new UK-wide Health and Social Care (HSC) levy,which would help to raise funds to reform social care. National Insurance contributions, which most employees and employers have to pay, will be increased by 1.25ppts.

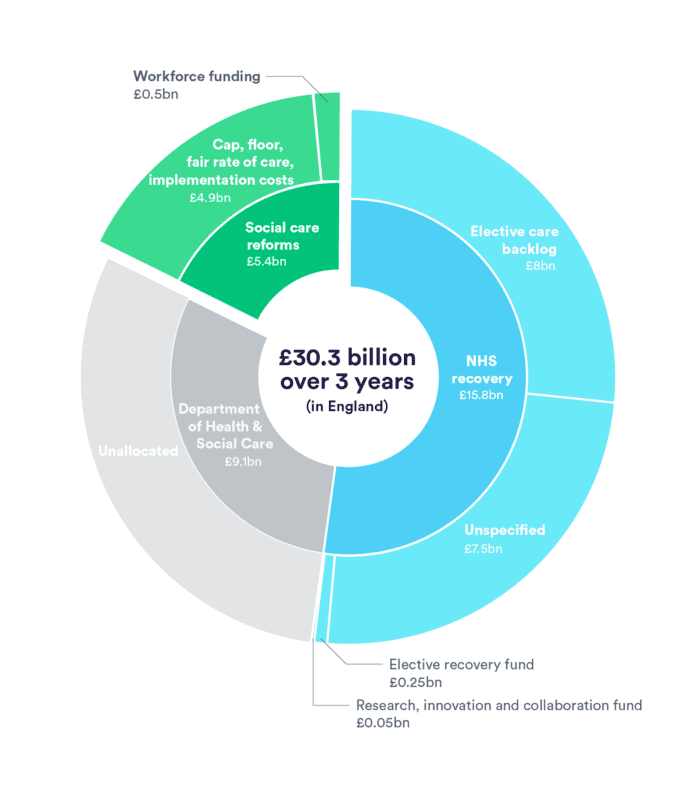

We estimate that the HSC levy and dividend tax increases are expected to raise £30.3bn over the next three years in England (see Box 3), with £15.8bn allocated to the NHS Recovery Fund, £9.1bn to the Department for Health and Social Care and £5.4bn for social care.

Means-Test and Lifetime Allowance

A majority of the £5.4bn, about £3.6 bn, will help to reform the ‘means test’ and the Lifetime Allowance of £86,000. From 2023, people with less than £100,000 – rather than £23,250 – will be able to receive some financial support to help them pay for social care (subject still to a needs test). People will also not have to pay any more than £86,000 on social care costs over their lifetime. This means that people who need social care will be able to keep more of what they own, and more people may be able to access help to pay for social care.

Wider Reforms including Workforce Development

The government has also promised to bring forward a wider plan for reform before the end of this year. This might include measures to improve the quality of social care, conditions for staff who work in social care, and support for carers. The remaining £1.7bn from the £5.4bn has been committed to these reform plans. At least £0.5bn will go towards developing the social care workforce, over three years.

Central Government Funding

The government is providing councils with £4.8bn of new grant funding between 2022/23 and 2024/25 for social care and other services, although it is not clear how much will be used for social care.

Council Tax increases and Adult Social Care Precept

Finally, councils will be able to increase Council Tax by up to 2% per year. Councils in England with social care responsibilities will also be able to increase the adult social care precept by up to 1%.

More Funding Still Needed

Even so, councils do not receive enough money from the government to pay for all the people who are entitled to support with social care. As a result, many people end up on waiting lists to get access to care and support, and this care is often not reflective of what people want or need to help them live independent lives.

Recommendation 1

The Government should invest in developing more innovative types of social care that can help people to live more independent and fulfilling lives. There is a great potential for technology to help with this.

Recommendation 2

The Government should urgently improve the pay and conditions for people who work in social care to make the sector a more attractive place to work. Develop a career pathway for people to have opportunities to develop and learn new skills.

Recommendation 3

The Government should invest in improving support for families and friends providing care informally (informal carers). This might include resuming and expanding day care and respite services post the Covid-19 crisis, and measures to improve carers’ health and wellbeing.

Camille Oung, The Nuffield Trust

Reforming Adult Social Care – Integrating Funding, Pay, Employment and Skills Policies in England

The Campaign for Learning’s report, Reforming Adult Social Care: Integrating Funding, Pay, Employment and Skills Policies in England, is based on seventeen contributions from experts in both the adult social care sector and the post-16 education, skills and employability sectors.

Three themes are common to most of the authors’ contributions – the scale of the adult social care sector in England, the complexity of policy making for the sector, and the need for greater integration of funding, pay, employment and skills.

Part One: The Adult Social Care Sector

- Camille Oung, The Nuffield Trust: The Funding and Delivery of Adult Social Care in England

- Duncan Brown, Emsi: The Employment Model of Adult Social Care

- Louise Murphy, Policy in Practice: Wages, Universal Credit and Adult Social Care Workers

Part Two: Strategic Reforms to Adult Social Care

- Paul Nowak, TUC: A National Care Forum to Fix Social Care

- Stephen Evans, Learning and Work Institute: A Long-Term Pay, Employment and Skills Plan for Adult Social Care

Part Three: Recruitment in the Context of a Skills-Based Immigration Policy

- Becci Newton, Institute for Employment Studies: Improving Pay and Job Quality in Adult Social Care

- Karolina Gerlich, The Care Workers’ Charity: Encouraging Young People and Adults to become Adult Care Workers

- Chris Goulden, Youth Futures Foundation: A Career in Adult Social Care: The Views of Young People

- Andrew Morton, ERSA: Targeting Active Labour Market Policies to Fill Adult Social Care Vacancies

Part Four: The Delivery and Design of Social Care Qualifications

- John Widdowson, Former FE College Principal: Embedding Emotional Support for Learners on Health and Social Care Courses

- Naomi Dixon, Education and Training Foundation: Supporting Post-16 FE Practitioners to Teach Social Care

Part Five: The Role of Post-16 Education and Skills Policies

- Elena Wilson, The Edge Foundation: Valuing Level 3 BTECs for 16-18 Year Olds Studying Health and Social Care

- Julian Gravatt, AoC: What Post-16 FE Can and Cannot do to tackle the Adult Social Care crisis

- Jane Hickie, AELP: Reforming Apprenticeship Funding and Delivery for Adult Social Care

- Gemma Gathercole, CWLEP: Adults Skills, Adult Social Care and Devo-Deals

Part Six: Adult Learning and Adult Social Care

- Susan Pember, HOLEX: The Wider Benefits of Adult Learning for Adult Social Care

- Simon Parkinson, WEA: Adult Learning for Adults in Social Care

- Campaign for Learning: Proposals for reform in England

Responses