Delivering the right kind of careers education in the interest of better representation

Let’s All Play Politics…

In 2020, Lewis Hamilton—simultaneously the most successful and only Black driver in Formula One—announced the formation of the Hamilton Commission alongside the Royal Academy of Engineering, which would undertake ten months of research into the lack of diversity in motorsport, despite the variety of jobs in the industry.

Last month, the Commission published its findings in a report titled Accelerating Change: Improving Representation of Black People in UK Motorsport, featuring concerning statistics, including that “only 1% of people employed in Formula 1 are from Black backgrounds.”

Along with the report came Mission 44, a Foundation to act on the recommendations made by the Commission, and to which Lewis has personally pledged nearly £20m.

Naturally, Hamilton posted about these developments across social media.

Scroll through the comments on any of those posts and you’ll arrive at rhetoric that has dominated his work both on track and outside of F1 throughout his career:

- – Black people just choose different careers

- – jobs should be awarded on merit, not the color of people’s skin

- – why are we promoting diversity for diversity’s sake?

- – stop whining and race

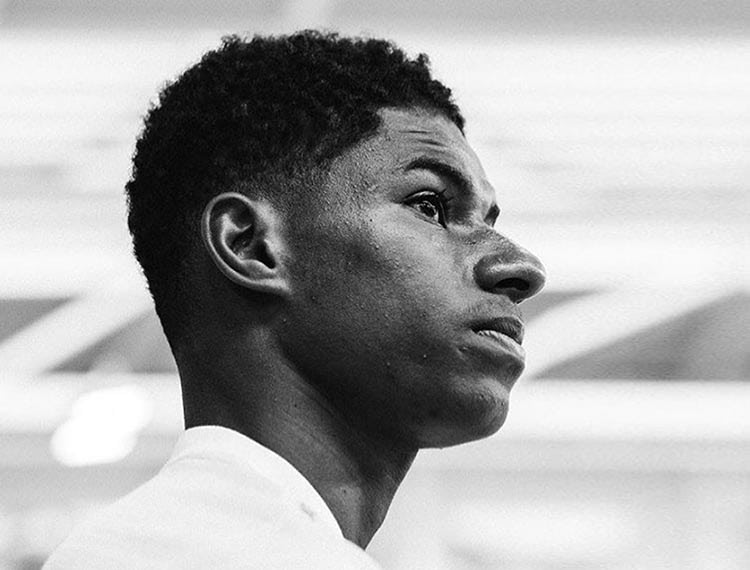

Also in 2020, Marcus Rashford — forward for Manchester United and England — ramped up his efforts to end child poverty in the UK when it became apparent that an overwhelming percentage of the student population in Manchester would not receive free school meals during the first lockdown.

Since then, his campaigns have gone national, forcing the government into action, he has:

- Partnered with FareShare, which raised over £20m

- Worked with Magic Breakfast and Macmillan, and

- Fought for better treatment of underprivileged young people

Then, in July 2021, he took a penalty for England in the Euros final. He missed. England lost.

The response from some of the public, armed with prejudices and anonymised social media accounts was disheartening and expected; but the vitriol did not only come from faceless crowds online.

In a private message to some of her colleagues, Dover MP Natalie Elphicke said:

“They lost – would it be ungenerous to suggest Rashford should have spent more time perfecting his game and less time playing politics?”

Yes, it would be ungenerous, but why?

Why is it important to nurture prominent people from under-represented backgrounds, and why does their activism matter?

Motorsport Valley

Lewis Hamilton has both witnessed and experienced a great deal of unfair treatment in his ascent to – and time in – F1. He’s spoken at length about the near-expulsion from school for an incident he was never involved in, the pushback he has gotten from higher-ups when trying to talk about racial issues, and the ‘wrath of emotions’ that scenes of police brutality in the US brought up.

The Hamilton Commission is an effort to turn those feelings into actionable research. It examines the causes of the lack of representation for Black people in motorsport, introduces case studies for a first-person view of the issue, and makes recommendations to the industry on how to make use of this intelligence.

For instance, some discourse argues that lack of interest in certain careers is to blame for under-representation of minorities.

The theory holds some truth but examining young people’s interaction with motorsport elucidates the mystery of why engagement is so low for certain groups of people: most English racing teams’ headquarters (Mercedes, Red Bull Racing, Renault, et al) are stashed away from the urban areas with the highest densities of ethnic minorities (Accelerating Change, p. 37).

Adding to that is the highly glamorised image of the sport – this tight, elitist collection of ten teams and twenty drivers, with offices in futuristic glass buildings in Motorsport Valley, the colloquially termed conglomeration of F1 HQs around Oxfordshire and the Midlands.

Lack of access begets low interest: later in the same chapter, the report states that “the ‘elite’ image of Formula 1 [risks] putting off candidates from non-Russell Group universities from applying for roles, the suggestion being that students would consider it a waste of time to apply as they would not have a high chance of securing employment” (Accelerating Change, p. 42).

This issue is not exclusive to motorsport – young people from minority racial and socioeconomic backgrounds shy away from some careers, such as finance, law, and STEM-based paths due to poor access. As the Commission itself says, the research shines a bright light on this specific industry, but it must act as an impetus to examine the world of work more broadly.

“Lewis Hamilton has blazed a trail through motorsport,” the report concludes (AC, 160).

“He set up the Hamilton Commission to help others have the opportunities to shine that all young people deserve.”

His “playing politics” has led to the creation of a new framework for how we support and educate students from underrepresented backgrounds. At the same time, he’s breaking a new record every time he gets behind the wheel: most wins in F1 (99), most race starts (265), and only driver to win a race in every season completed, among many other accolades.

Though these are extraordinary statistics, he remains representative of Black youth with high potential, held back by circumstance but resilient throughout; he says it himself:

“The one thing that connects the boy who was told he had no potential in 1996, with me today, is opportunity. […] I am the same boy who got told he’d never achieve anything” (Accelerating Change, 6).

If I Have Nothing Else

“He’s a very good young player,” Cristiano Ronaldo said of Marcus Rashford in 2016.

“I see some of myself in him for sure. […] He has an amazing future.” At this time, Rashford was enjoying a success-laden debut.

A year before, The Guardian highlighted him in a Next Generation piece on the 20 promising talents in Premier League clubs.

Parallel to professional success, much like Lewis Hamilton, Rashford is inspired by his own working-class background; on his journey to dedicated charity and activism Rashford wrote to the Prime Minister: “[…] my mum worked full-time,” he wrote, “earning minimum wage to make sure we always had a good evening meal on the table. But it was not enough. The system was not built for families like mine to succeed, regardless of how hard my mum worked.”

In fact, this letter was part of Rashford’s campaign for extending the free school meal provision, which prompted a U-turn that rightly lingered in the news for months: extension of free school meals and “a £170m Covid winter grant scheme to support vulnerable families in England and an extension of the holiday activities.”

Of course, career highs don’t come without some lows. It’s true for all athletes, including Rashford – in July this year, he missed a penalty for England in the highest-stake match for them since 1966. Immediately afterwards, the country held its breath for what would follow; racist tweets, the defacement of his mural in Manchester, and the now infamous “playing politics” comment.

Rashford’s response was model leadership: a post in which he apologises for missing the penalty and expresses gratitude for the messages of support he’s received, from his own community in Manchester, and beyond:

“The communities that always wrapped their arms around me continue to hold me up. I’m Marcus Rashford, [a] 23-year-old, Black man from Withington and Wytenshaw, South Manchester. If I have nothing else, I have that.”

Below that message are photos of letters from children, writing about Rashford as an inspiration, a hero; children who are watching him play football and politics, succeed and fail, ace his craft and help families in need, children who are seeing themselves in him.

Responsibility

It is significantly more difficult for Lewis Hamilton and Marcus Rashford to exist in their respective sports as who they are than it is for their white counterparts from more affluent backgrounds. It’s surely not their responsibility, then, to solve the world’s social issues in half a lifetime each.

Both Hamilton and Rashford have felt compelled to act. In the introduction to the Commission’s report, Lewis says he couldn’t wait to to act anymore after noticing a profound lack of representation in his F1 team (Accelerating Change, p.7);

Rashford, in turn, says: “When you get to the position I’m in now, I feel like if [children] are in need, and they don’t have anyone fighting for them, I should be the one that does it, really.”

This should never be the case. In these children’s corner, fighting for them, must be both individuals and institutions, in the public and private sectors alike, who have the power to create opportunity; and by deriving insight and inspiration from Hamilton and Rashford, we can begin to do just that.

The positive news is that, little by little, we are beginning to notice change: firstly, as mentioned, Rashford’s campaigning forced the government into a U-turn on free school meals, giving more young students the opportunity to learn, unhindered by a lack of access to food. In parallel, the Hamilton Commission’s report is the backbone for the formation of Mission 44, a foundation to commit to improved diversity in the industry through early education.

Lewis Hamilton has driven the F1 CEO, Stefano Domenicali, to speak about increasing diversity in the sport. That’s no small feat, considering the awful few commitments made to ensuring racial justice and equality from F1 or FIA officials before Lewis Hamilton started to make noise.

On a more local scale, this learning will have a long-lasting impact: as Trustees of the Patrick Morgan Foundation, we will be going into partner schools in the autumn with new STEM-related learning and resources for students aiming for a science-led career, whether it be in motorsport or otherwise.

More to the point, this discourse and political activism has opened the door to conversations about how grassroots organisations can be supported in delivering the right kind of careers education in schools, in the interest of better representation. More funding and corporate support has enabled us, and many foundations like us, to be better prepared in the way we both train and inspire students in their career pursuits of choice, and is there any better way to tackle a systematic issue than at its root?

Let’s All Play Politics

As established, minority young people who dream of entering careers where they are under-represented face complex barriers, which often enforce one another: lack of access, poor education, no support, and socioeconomic background, to name a few.

The problem did not develop overnight, so it won’t just take one Lewis Hamilton or one Marcus Rashford publicly succeeding to fix it, but what’s a marathon if not a series of small steps? Using not only their accomplishments, but their message and sense of civic duty, we can inspire people from the same backgrounds to reach higher than they ever have.

In the meantime, the public and private sectors have their own job to do: create ample opportunity, so that when the next generation does reach forward, they’re met with doors that open easily.

In a recent piece, Labour MP Jess Phillips writes about Rashford, post-Euro 2020 discourse, and the value of non-politicians campaigning, underlining the egregiousness of political gatekeeping.

“So let’s play politics,” she says, “because it’s personal to each and every one of us.”

We ought not to dismiss the Hamiltons and Rashfords of the world, but encourage them, learn from them; join them.

With stakes this high, let’s all play politics.

Marina Hercka, Trustee, and James O’Dowd, Founder of the Patrick Morgan Foundation

Responses