Why should employers invest in training in a flexible labour market?

The recent ‘Slouching towards utopia: an economic history of the twentieth century’ by the US economist J Bradford DeLong shows a turn in the world economy around 1870, with the development of globalisation, the modern corporation, and the industrial research lab. It began first in the USA, and then continued in other countries.

This produced a change in the trend of innovation and hence, economic growth and prosperity. The pre-First World War period saw the first phase of this growth – but with high inequality. After the two world wars and the inter-war period, these trends – globalisation, major corporations and industrial research – were enabled to take further major steps by government support towards full employment, in the Keynesian consensus.

The Wilson world of the 1960s and 1970s

The description of a world in which major corporations were dominant, ran industrial research, and trained their workers on the new processes and machines resulting from their innovations – supported by government – is the world we used to know.

We can call it ‘Wilson-world’ after Harold Wilson’s ‘white heat of the technological revolution’ speech.

Industrial Training Boards ran levy systems that funded training outside the biggest companies that ran their own. These were paid for by employers, but supported and encouraged by government. In Wilson-world, it was common for people to work within the same firm for many years, developing skills as technologies used by the firm changed.

The neoliberal turn from 1979

In the UK, what appears internationally as ‘the neoliberal turn’ really started with Margaret Thatcher from 1979. Later, governments continued the same themes, so changes have now gone far further. The latest attempt to move from gradual neoliberal change to a crash-course of neoliberalism (Liz Truss) has crashed, but the ideas and the themes are still widely held and, perhaps particularly, held by business owners and managers as well as some politicians.

A ‘neoliberal-world’ involves entrepreneurs innovating and contracting with other entrepreneurs to implement and market their innovations. Entrepreneurs contract with other entrepreneurs, including self-employed labour-only businesses, for the work they want done. If workers are entrepreneurs they will invest in their own skill set, and the prices agreed for the sub-contract will reflect the market value of the skill set.

The real world

The real world involves a mixture of both neoliberal-world and Wilson-world. This mixture has conflicts and is unstable.

7m-8m job starts a year

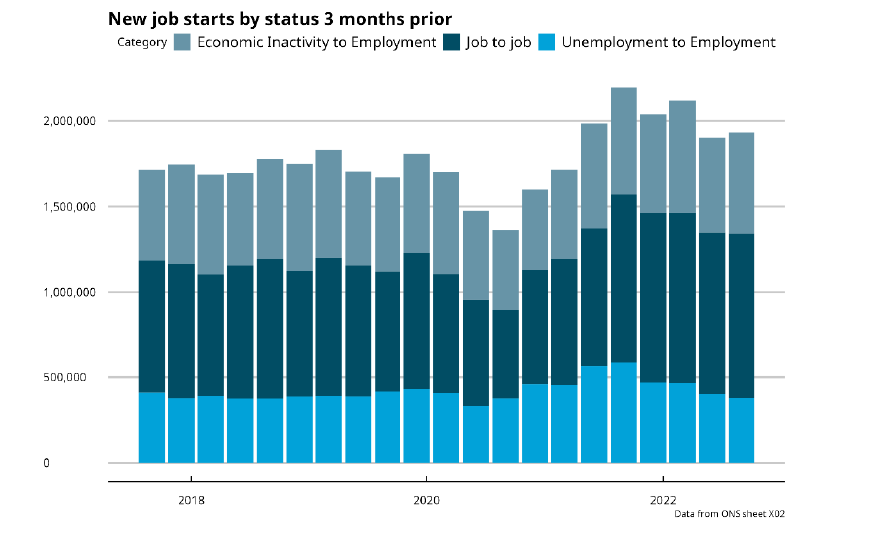

The current version of the mixture has a high level of job movements (see Chart 1). There are between 1.5 million and 2 million job starts each quarter (slightly higher immediately after reopening from lockdowns). Over a year, that is between 7 and 8 million job starts, between 20 and 25% of the total number in work.

Chart 1

This is also an underestimate, as one of the characteristics of self-employment (and to some extent of agency work) is that one stays in the same status while working in or for a number of settings, which for employees would be counted as separate jobs.

The very large number of job-starts from inactivity do show some effect of starts by previously inactive full time students in further and higher education between the July-September and October-December quarters. But in other quarters, 500,000 or more economically inactive people start jobs (which is bigger than the number of job starts from unemployed people almost all quarters).

These flows are counterbalanced by flows in other directions (see Chart 2). A rise in employment is a result of the net flow. The chart shows the flows in July-September 2022. The dark ends of the lines show the ending point of the flow.

Chart 2

Contingent work

Contingent work is where there is a degree of flexibility that involves some movement towards people having sub-contracted work. Contingent work is wider (and longer standing) than the ‘gig economy’ considered as working for internet platform firms.

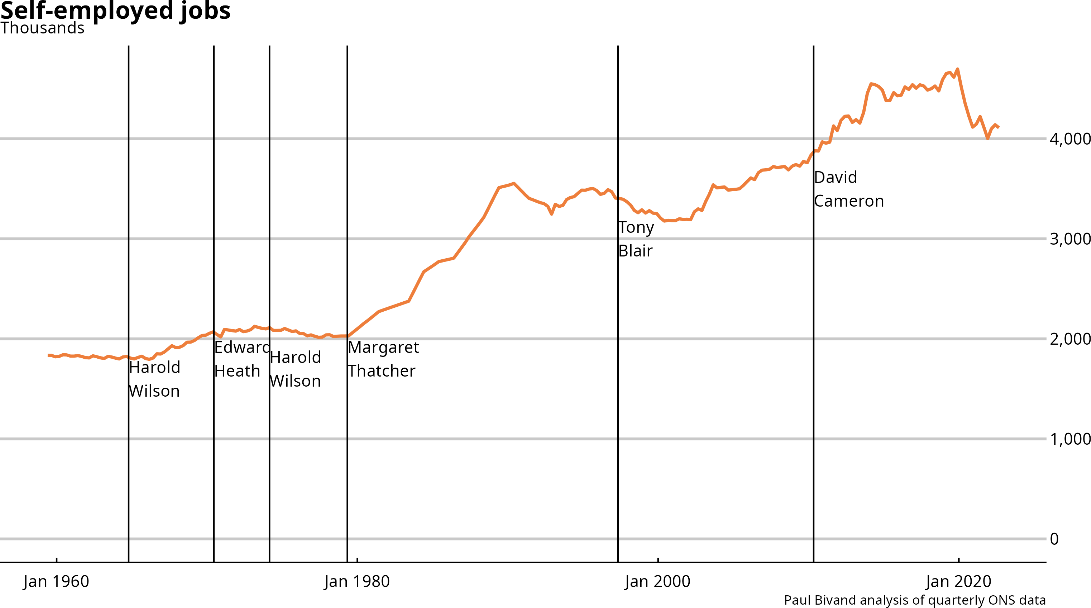

The oldest and most basic form is self-employment (see Chart 3). This was around 2 million before the ‘neoliberal turn’ of 1979. Because self-employment is seen as entrepreneurial, it has had favourable tax treatment, partly reversed in the most recent period (IR35 regulations). As a percentage of jobs, self-employment reached 12% in 1989, before falling to 10.5% in 2002, then rising to 13.5% in 2014, remaining close to that level until 2020.

Chart 3

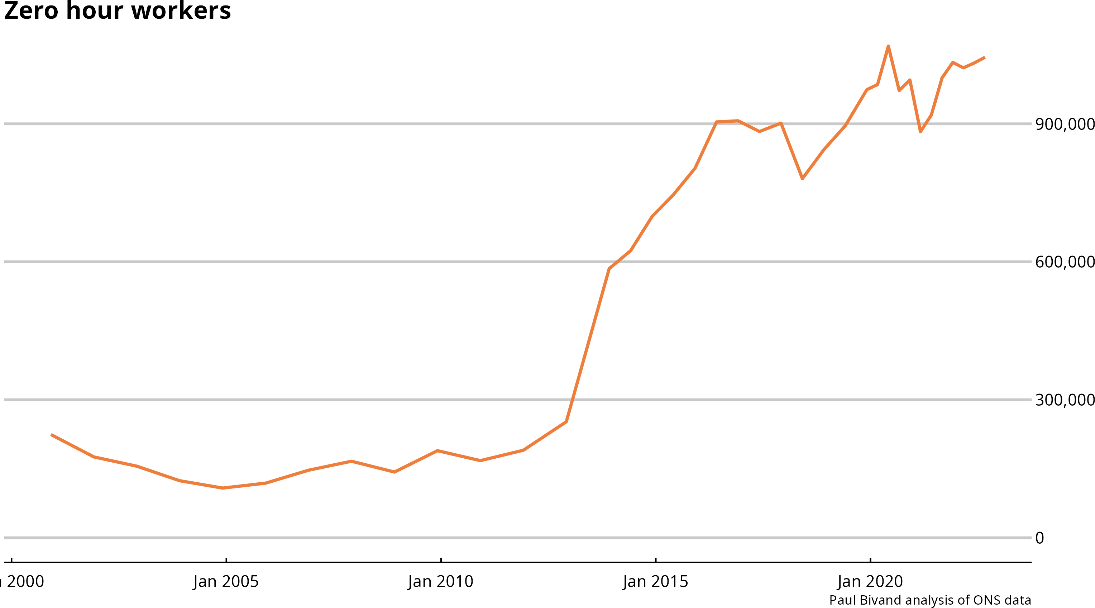

Over time, the forms of contingency change. The growth of zero-hour employee contracts (see Chart 4), largely since 2001, is the most recent of a series of moves towards contingency, and in some cases looks as though employers did not know they could do it until it hit the headlines.

Chart 4

Employee forms of contingent employment are on top of this. The Work Foundation’s Insecure Work Index identifies 19.8% of the workforce as having ‘severe insecurity’, with a further 33.0% having ‘low/moderate insecurity’.

These include self-employment. Less than half the workforce (47.2%) had no forms of insecurity. In the context of training, this means that 47.2% worked in firms where employer investment in training would be logically part of an employment package.

Employer investment in training

In Wilson-world, the employer invests in skills development. The employer pays, so expects the lion’s share of the return. The wage of the trained worker is a little higher than the lower-trained workers, while the job may be more secure than for the untrained. Employers and workers can work together to ‘grow the pie’ so the benefits of growth are shared. The role of government is partly to minimise conflicts, but also to incentivise both innovation and training as two sides of the same coin.

Individual investment in training

In neoliberal-world, everything is contingent. Job security is opposed by ‘creative destruction’. If there is no return to employers from paying for training as individuals leave them to find higher pay, employers would not be acting rationally to invest in training. And it would be even less rational for one entrepreneur to invest in the skills of their contractors if they cannot tie down a contract so that they – the commissioning employers – gets a return.

Workers are often satisfied with the more contingent forms, when asked in surveys. But in the neoliberal-world, it is for individuals and employees to be more entrepreneurial about their careers, skills-set, upskilling and reskilling.

The neoliberal-world usually sees little role for government in employer investment in training. On the other hand, if government does get involved, then entrepreneurs can take advantage of that (and lobby for more advantage).

Recommendation 1

Businesses need to recognise that their contractors need incentivising to gain the necessary certifications. This does mean contract values need to include the market value of qualifications (rather than assume government will fund them for free).

Recommendation 2

The adult skills world needs to recognise the existence of neoliberal-world and develop policies to address learning in that context. The failed Individual Learning Accounts were an early attempt to address the changing world. The continuations in Wales and Scotland have been small and restricted to public funding in priority sectors for insecure workers, and so do not fit into the neoliberal paradigm.

A new Individual Learning Account that fitted better into neoliberal-world could resolve the information asymmetry (the worth of courses) by requiring that qualifications are regulated, but having a regulated funding arrangement similar to auto-enrolment pensions into which employers and employees paid.

Self-employed people could (as with pensions) avail of similar systems. This would generate funds rather than requiring public funding. Public information using open data can provide information on the returns to qualifications.

Recommendation 3

For adult skills, living costs must be addressed, rather than just course fees. If people are giving up time they could be earning to train on their own account, then they need to be able to draw down living cost funding as well as course fees and training materials. In neoliberal-world, this needs to come from their ILA savings.

By Paul Bivand, Labour Market Consultant

This article is part of Campaign for Learning’s series: ‘Driving-up employer investment in training – pressing the right buttons’.

Part One: Employer investment in context

- Louise Murphy, Economist, Resolution Foundation: Investment in the round

- Dr Vicki Belt, Deputy Director, Enterprise Research Centre, Warwick Business School: UK enterprises and investment in capital and training

- Becci Newton, Director, Public Policy Research, Institute of Employment Studies: Employer investment in training in England

Part Two: Drivers of employer investment in training

- Neil Carberry, Chief Executive, Recruitment and Employment Confederation: Derived demand, British management and employer investment in training

- Ewart Keep, Professor Emeritus, Education Department, University of Oxford: Strategies to drive-up employer investment in training

- Sam Alvis, Head of Economy, Green Alliance: Transitioning to net zero, green skills and employer investment in training

- Dan Lucy, Director of HR, Institute of Employment Studies: Job quality, job design and driving-up employer investment in training

- Natasha Waller, Policy Manager, LEP Network: Local inward investment, business support and employer demand for training

- Jovan Luzajic, Acting Assistant Director of Policy, Universities UK: Universities, R&D, business innovation and meeting employer skills needs

- David Hughes, Chief Executive, Association of Colleges: FE colleges, business innovation and meeting employer skills needs

Part Three: Increasing employer investment in training

- Paul Bivand, Labour Market Consultant: Why should employers invest in training in a flexible labour market?

- Aidan Relf, Skills Consultant: Why should employers invest in training with large net worker migration into the UK?

- Stephen Evans, Chief Executive, Learning and Work Institute: Raising employer investment in training

- Robert West, Head of Education and Skills, CBI: Increasing employer investment in training

- Lizzie Crowley, Skills Policy Adviser, CIPD: Encouraging employer demand for training

- Anthony Painter, Director and Daisy Hooper, Head of Policy and Innovation Chartered Management Institute: Increasing employer demand for management training

Part Four: Raising employer demand for publicly funded post-16 education and skills

- Jane Hickie, Chief Executive, AELP: Increasing employer demand for post-16 apprenticeships in England

- Mandy Crawford-Lee, Chief Executive, UVAC: Increasing employer demand for level 4-5 technical education in England

- Ian Pryce, Principal, The Bedford College Group: Increasing employer demand for higher technical education in England

Part Five: Raising employer demand for work placements

- John Widdowson, Board Member, NCG: Increasing employer demand for work placements for level 3-5 vocational courses in England

- Stephen Isherwood, Joint Chief Executive, Institute of Student Employers: Increasing employer demand for undergraduate work placements in England

Responses